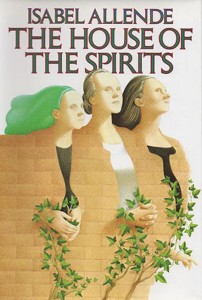

Craig Fisher is an Associate Professor of English at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina, where he teaches film studies as well as comics classes. Although Fisher teaches some infamously challenged books in his courses, he had never experienced censorship first hand until last October, when his friend and occasional colleague, Mary Kent Whitaker, sent him a disturbing email. A book in her curriculum, Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits, was being challenged for removal by an upset parent.

Craig Fisher is an Associate Professor of English at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina, where he teaches film studies as well as comics classes. Although Fisher teaches some infamously challenged books in his courses, he had never experienced censorship first hand until last October, when his friend and occasional colleague, Mary Kent Whitaker, sent him a disturbing email. A book in her curriculum, Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits, was being challenged for removal by an upset parent.

Although Fisher hadn’t read the book, his 17-year old son, a junior at Watauga High and a former student Whitaker’s, had done so the previous year without issue. Fisher is an actively involved parent, typically going to Whitaker’s class as a guest speaker once a semester during the unit on Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (itself the occasional target of would-be censors). After reading the concern in Whitaker’s email, he wanted to help.

For the past five months, Fisher has been directly involved in fighting back against those that would ban The House of the Spirits. He spoke with CBLDF about his experiences battling censorship in his community, including his concerns about the lingering affects of the challenge as well as his hopes for what’s next at Watauga High.

Craig, after you received the initial email from Mary Kent Whitaker, what did you do?

Started following the controversy. The parent that complained about teaching The House of the Spirits and filed the challenge did so on October 14th or so, and I heard from Mary Kent at the end of October. I began following the challenge and paying more attention to it.

According to the procedures of our local board of education, the challenge has three levels. The first is that a random sample of parents, teachers, students and personnel from the high school get together in a seven-person committee to read the book and determine whether or not it should stay in the curriculum. That happened in November, I believe, and it passed unanimously. After that, it was the parent’s appeals that bumped it up to the next level of determination, which was a five-person panel appointed by the Board of Education from educators from other schools and community representatives, such as a pediatrician who would evaluate the book. At that point, I organized a teach-in at Appalachian State where we had a number of people speak about keeping the book in the curriculum. I helped to organize that.

Before the challenge, had you read The House of Spirits?

I hadn’t. When Nate, my son, was reading it, he said I should but I was too busy at the time. I did read it before I got involved and I think the claims that the book is pornography don’t make any sense. There is sexual violence in the book, there is disturbing material, but it’s all to capture the history of the military coup in Chile. But there’s nothing titillating about it; it’s a very serious, adult book. It’s a story of redemption and it’s a serious work of art.

Have you had any interactions with Chastity Lesesne, the parent who filed the complaint?

I have not. One of the things I didn’t want to do was personalize it. I know other people I’ve worked with on the book challenge have chatted with her, but I haven’t.

Have you had the opportunity to hear her speak about her point of view?

Yes — at the second stage of the appeals, where the community members were voting on the book, the way that it worked was that each side got a half an hour to speak. Mary Kent spoke about keeping the book in the curriculum and why her decision to place the book in the curriculum was pedagogically sound. Then Chastity Lesesne spoke for a half an hour as well, and her arguments really boiled down to two things. One, that the book is pornographic. Second was the process for parents who objected to books taught in the class.

For example, if someone didn’t want to read The House of Spirits, Mary Kent let them read Moby Dick — mostly because they are comparable in terms of complexity. Some of the parents said that the alternative, kids going to the library while the class talked about The House of Spirits, wasn’t rigorous. I can kind of understand that. As parents, they have the right to lobby the school to develop a more robust alternative. That’s fair. What I object to is that in order to develop that better alternative, do we have to take The House of Spirits out of the classroom? I don’t think so.

From the parental side of your perspective, at what point would you feel comfortable stepping up and saying that you felt material was inappropriate? Or would you let your child be the one to make that decision?

I think it depends on the child. I guess I would like to let my kid make the decision as much as possible. It’s hard for me to think of anybody being so reckless that they would teach something in the classroom that was out and out pornography. But even that — I would have to think twice or three times before I would tell my child he couldn’t read something. If I did reach a point where material used in class bothered me, I would just have my child do the alternative. I wouldn’t ask that the book be removed from the classroom. One of the things that happened at the last Board of Education meeting was that a lot of people spoke for and against the book. It seemed to me that the people speaking for the book trusted the young adults more. We were saying, you know, that they are young adults; they’re going to have to deal with all kinds of media when they get out of high school. Reading something adult is challenging and it can be disturbing, but it’s an important experience. The other side was arguing that they are still children and need to be protected. By the time my kid gets to 15 or 16, my job as a parent isn’t to protect them. It’s my job to advise and guide, but not protect. Especially from a book.

What value do you see in keeping the book and what is driving you to continue advocating for it?

There are a couple of things. One is that since I have gone in and taught in Mary Kent’s class, I’ve seen the way she structures her syllabus. She does it around a particular theme, which is how to keep a family together and how to maintain a family in very ideologically and politically trying times. Persepolis is a good example of that, too. She’s thought a lot about the syllabus and pulling The House of Spirits out of it last semester while the challenge was going on sort of tore the heart out of it. The syllabus was designed to compare and contrast across national boundaries. One value of keeping it in there is to continue showcasing books from different nations and how they are similar.

I stay motivated because it’s a good book. It’s a great introduction to Latin American literature and magical realism.

Do you feel that it’s important for teachers to redirect students that are uncomfortable or confused about materials to other resources, like their parents, and to make sure that there is an open dialogue to process challenging books?

Yeah, absolutely. Ultimately it comes down to the question of: Would you rather have your kid reading this without any guidance or with a really, really good teacher? And my answer is that a really good teacher will open a dialogue and start discussions about it. That’s infinitely preferable.

If the book is banned, do you feel like this opens a door in the school system to scrutinize other pieces of the curriculum?

Oh, yeah. I’ve gotten to know a lot of the teachers over there and many of them have told me that they use things in their class that they aren’t going to use anymore already just based on everything that’s gone on already. I know it’s a cliché to say so, but censorship is a slippery slope. One of the problems I’ve had with this process all along is that in the bylaws of the local Board of Education, the book is supposed to remain in circulation. They read that in the most conservative way possible, which is that the book should remain in circulation in the library, but not in the classroom. So they pulled it out. I’m afraid that if this goes through, there will be other challenges when other books get banned, or four and five month periods where the teachers don’t know if they can use those materials. I think that would be a terrible thing — not just for the book banning, but also for the loss of time. It’s de facto censorship.

I’m optimistic that the Board of Education will uphold keeping the book in the curriculum, and part of that is that there’s been a groundswell of support from other parents.

Have you ever been told that a book was off limits?

That’s an interesting question. I went to a Catholic school and I know that certain books weren’t in the library there. But my parents took the approach of benign neglect, which was, “you read your comics, you read your science fiction, you read your nerd culture, I don’t want to know much about it.” As a consequence, I read some books probably before I should have. I read The Exorcist in sixth grade and some of the images of it stayed with me for quite awhile. But I was reading. And even when you’re reading things that can challenge you, or frighten you, they become part of the culture that makes you who you are. And I don’t think that reading things disturbing to you is necessarily a bad thing.

After months of contentious and sometimes divisive debate, the fate of Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits is set to be decided tonight. The school board will meet for final comments and to make their decision. For more on the story and what you can do to help, visit CBLDF’s coverage here.

If you want to share your own true tale of censorship, we want to hear about it! Email casey.gilly@CBLDF.org to share your story.

We need your help to keep fighting for the right to read! Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!