Looking back on the anti-comics crusade of the 1950s, it is perhaps too easy to fall back on stereotypes: dull, repressed suburbanites trying to force their children to conform and read only what they considered to be “quality literature.” But a classic essay featured from the archives of Commentary magazine paints a more complex picture of at least one comics-doubting parent and his comics-loving 11-year-old son in 1954.

Looking back on the anti-comics crusade of the 1950s, it is perhaps too easy to fall back on stereotypes: dull, repressed suburbanites trying to force their children to conform and read only what they considered to be “quality literature.” But a classic essay featured from the archives of Commentary magazine paints a more complex picture of at least one comics-doubting parent and his comics-loving 11-year-old son in 1954.

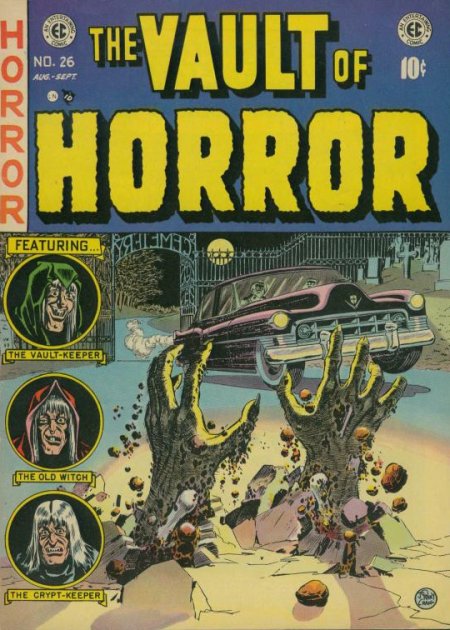

Robert Warshow was a cultural critic and editor of Commentary since shortly after its founding in 1945. A tempered appreciator of pop culture including the Marx Brothers and the newspaper comic Krazy Kat, Warshow was perhaps slightly more open-minded than the mainstream of adults when it came to the E.C. Comics that his son Paul devoured. The elder Warshow personally failed to grasp the appeal of the publisher’s horror spoofs like Panic (although he did admit to having read a few issues of Mad “with a kind of irritated pleasure”), but conceded that he was unable to intellectually justify preventing Paul from reading what he enjoyed.

With the bemused detachment of an anthropologist, Warshow recounted his son’s membership in the E.C. Fan-Addict Club. Obviously a doting father, he even took Paul and some friends to visit the E.C. offices in New York, where they met Bill Gaines and caught a glimpse of artist Johnny Craig. After Gaines testified before the Senate that he was proud of his work, Warshow saw fodder for an ongoing respectful debate with Paul over the value of comics:

I did not fail to clip the report of Mr. Gaines’s testimony from the Times and send it to Paul, together with a note in which I said that while I was in some confusion about the comic-book question, at least I was sure I did not see what Mr. Gaines had to be so proud about. But Paul has learned a few things in the course of the running argument about comic books that has gone on between us. He thanked me for sending the clipping and declined to be drawn into a discussion. Such discussions have not proved very fruitful for him in the past.

Warshow was highly skeptical that comics could have any effect on the behavior of well-rounded upper-middle-class youngsters like Paul, observing that “the bloodiest of ax murders apparently does not disturb his sleep or increase the violence of his own impulses.” He largely scoffed at the simplicity of Fredric Wertham’s arguments in Seduction of the Innocent, which he labeled “a kind of crime comic book for parents, as its lurid title alone would lead one to expect.” Many of the “pathologies” that Wertham identified were in fact near-universal childhood experiences, he felt:

When Dr. Wertham tells us of children who have injured themselves trying to fly because they have read Superman or Captain Marvel, one becomes skeptical. Children always want to fly and are always likely to try it. The elimination of Superman will not eliminate this sort of incident. Like many other children, I made my own attempt to fly after seeing Peter Pan; as I recall, I didn’t really expect it to work, but I thought: who knows?

Nevertheless, Warshow did tentatively express support for some sort of industry regulation, which would in fact be self-imposed as the Comics Code Authority only a few months after his essay was published in 1954. Despite his balanced consideration of other forms of popular culture, he admitted that “I think one must accept Dr. Wertham’s contention that no real problem of ‘freedom of expression’ is involved, except that it may be difficult to frame a law that would not open the way to a wider censorship” of other media. But he saw the futility of trying to ban comics altogether:

If the publication of comic books were forbidden, surely something on an equally low level would appear to take their place. Children do need some “sinful” world of their own to which they can retreat from the demands of the adult world; as we sweep away one juvenile dung heap, they will move on to another.

Sadly, Robert Warshow died of a heart attack at 37 in 1955, a little over a year after the publication of his E.C. Comics essay. Although he was not around to see much of how the industry was transformed under the Code, there is another interesting postscript to the story. After the essay ran in Commentary, Fredric Wertham sent a letter directly to 11-year-old Paul urging him to carefully consider his father’s views, despite the fact that Wertham himself came in for a fair bit of criticism in the article as well. In an unfailingly polite reply, Paul managed to hold his own:

Dear Dr. Wertham:

Thank you very much for your letter. I have read my father’s article and I think it is very good. I don’t agree with all the things in it. I don’t think comics do much harm to children. I don’t think they are all good though. Most children learn enough to know if a comic is sensible. Only a few would take an unlikely story seriously. I don’t take them seriously but I enjoy some of them. Thank you again for your letter.

Best wishes, Paul Warshow

P.S.: I would very much like to meet you.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2016 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.