When Bill Gaines testified in defense of comics before the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency in 1954, he was staking out a lonely position to say the least. The establishment view of comics ranged from bemused indulgence to outright fearmongering à la Fredric Wertham, but hardly anyone entertained the notion that they were worth defending on First Amendment grounds. Decades before the establishment of CBLDF and the advent of comics in libraries, though, one familiar ally was already speaking up on their behalf: the American Civil Liberties Union.

When Bill Gaines testified in defense of comics before the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency in 1954, he was staking out a lonely position to say the least. The establishment view of comics ranged from bemused indulgence to outright fearmongering à la Fredric Wertham, but hardly anyone entertained the notion that they were worth defending on First Amendment grounds. Decades before the establishment of CBLDF and the advent of comics in libraries, though, one familiar ally was already speaking up on their behalf: the American Civil Liberties Union.

The ACLU had been founded three decades earlier to defend the civil liberties of World War I-era dissenters including conscientious objectors and radicals of all stripes. Since then, it had taken principled but often unpopular stands in high-profile cases such as the Scopes ‘Monkey Trial,’ and was the only national organization to speak out against the federal government’s internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. In the very same year that the Senate was preoccupied with the alleged evils of comics, the ACLU and the NAACP won a landmark victory in Brown v. Board of Education.

It’s not so surprising, then, that the ACLU took up a lonely defense of comics alongside Gaines and other industry insiders. The organization’s statement to the Senate Subcommittee was expanded and published the following year as a 15-page pamphlet titled Censorship of Comic Books: A Statement in Opposition on Civil Liberties Grounds. Thanks to the HathiTrust Digital Library, this publication–most likely the first ever detailed Constitutional defense of comics–is now available online.

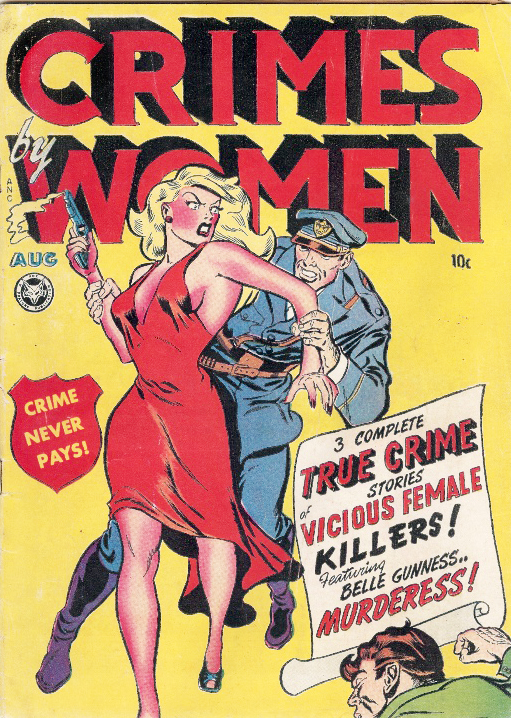

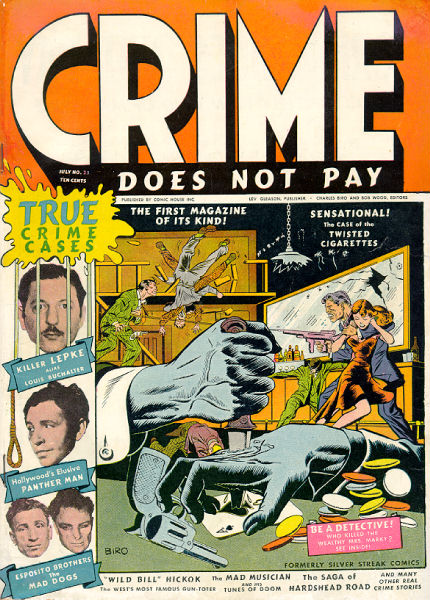

While Gaines’ memorable testimony concentrated on the horror comics that were EC’s bread and butter, the ACLU’s argument focused instead on the crime genre. The whole point of the Senate hearings, after all, was to determine whether comics had the power to turn children into hardened criminals. Like horror comics, the crime variety was unabashedly lurid and sensationalistic. Among the most popular was Crime Does Not Pay, which managed to give lip service to moralism while also communicating through its title design that the appeal of the book was, in fact, the crime. But as the ACLU pointed out, no researcher had been able to definitively establish a link between readership of crime comics and juvenile delinquency. Without such evidence, they found “no justification for cutting into a basic right guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution, a free press unhampered by governmental influence.”

This debate undoubtedly seems familiar to modern-day gamers–a fact not lost on CBLDF or the ACLU. Another similarity lies in the 1955 pamphlet’s repudiation of the idea that children were the sole audience for comics:

This debate undoubtedly seems familiar to modern-day gamers–a fact not lost on CBLDF or the ACLU. Another similarity lies in the 1955 pamphlet’s repudiation of the idea that children were the sole audience for comics:

[I]t is unreal to discuss the problems of censorship of comic books in a context which implies that only children would be affected. There is ample evidence that a large part of the comic book readership is adult. The ACLU is opposed to the prior censorship of reading material for adults, even if children may obtain access to such material, for we believe that the First Amendment flatly prohibits it. To condone pre-censorship for children is to risk abandonment of all material to the censor, since in one way or another youngsters are apt to obtain any book at some time.

The ACLU also dismissed the idea of a sales ban for minors at the retail level, which would place an undue burden on shopkeepers and probably spur a brisk black market in any case:

There is ample evidence that a prohibition always heightens interest in the banned product, and it can be expected that ‘bootleg’ sales will spring up, especially as children will realize that comics are legally unobtainable….It is common knowledge that comic books are passed from one child to another and if one undesirable comic book gets into the hands of a single child, a great number of children will be exposed to it. [In communities that have such laws], each bookseller is faced with the task of determining who is a qualified buyer, and deciding which comic book is outside the pale. This law may be more difficult to administer than the law forbidding the sale of liquor to minors.

Also on the subject of retailers, the pamphlet condemned local police raids similar to the one that would lead to the founding of CBLDF in 1986:

We are opposed to the wholly improper procedure of certain law enforcement officers who, instead of commencing prosecutions against the publishers and wholesale distributors of magazines–businessmen economically able to defend themselves against lawsuits–rather threaten the small, local retail booksellers who are in no position to resist official coercion. What happens in these cases, in effect, is that a ban on particular books results without any hearing on the merits of the book itself and the protection of a jury trial….

Between the time of the Senate hearings in April 1954 and the ACLU pamphlet’s publication in 1955, the industry self-imposed the Comics Code in a desperate attempt to stave off government censorship. The ACLU also took a dim view of that forced conformity, however:

Collective adherence to a single set of principles in a code has the effect of limiting different points of views, because individual publishers–as well as writers–are fearful of departing from the accepted norm lest they be held up to scorn or attack and suffer economic loss. (The ‘seal of approval’ granted by the Code to approved publications also places economic pressure on local distributors, who are also under surveillance by local pressure groups.) But the variety of ideas is the lifeblood of a free society. Whatever evil exists in the restraint of competition in our economic life pales in significance when compared to the dangers of monopoly or uniformity of ideas.

To sum up their argument, the authors of the pamphlet borrowed a stirring passage from ACLU Executive Director Patrick Murphy Malin’s testimony before another notorious Congressional committee, the 1952-53 House Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials:

There may be, in the absence of censorship, some risk that some persons along the line may possibly get hurt. But our life is founded upon risk. There is risk–and indeed certainty–that every day many people will be killed by automobiles, and yet we leave automobiles on our streets. I suggest to you that the institution of free speech is surely just as vital to our society as the automobile. Risk there is in all life, and we must take this risk on the side of freedom. That is the glory of our way of life. Censorship is abhorrent to Americanism.

Although it may be tempting to leave the defense of comics on that ringing high note, we would be remiss in not calling attention to the ACLU pamphlet’s appendix of quotations from a variety of sources, gathered to demonstrate that there was no consensus on the juvenile delinquency question. Take for instance the assessment of Ramsay County, Minnesota probation officer John J. Doyle, who offered this ranking of the real negative influences on youth: “I would place the pool hall first, undesirable movies second, lurid magazines third, dramatic newspaper stories fourth, and comic books last.”

There is much more to be found in the full text of the pamphlet here. Three cheers for the ACLU of yesterday and today!

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2017 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.