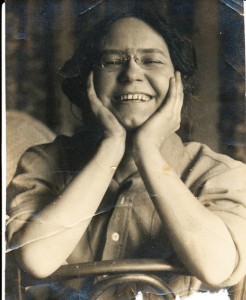

When Lou Rogers first tried to break into political cartooning around 1908, “Editors said there were no women cartoonists,” a reporter and childhood friend recalled about 15 years later. “They said women couldn’t even draw jokes. They hadn’t any humor” (Lewiston Daily Sun 1924). The naysayers were almost right on one score: Rogers was indeed among the first female professional cartoonists in the United States. But on the other points, she soon proved them wrong, building a decades-long career through hard work and sheer determination.

Annie Lucasta Rogers was one of seven siblings raised on a farm in northern Maine, where their father owned several logging camps. Their mother, observed Rogers’ reporter friend in the Lewiston Daily Sun in 1924, was “the sort of woman who would have made a remarkable journalist had that opportunity been open to her.” Rogers herself showed an early talent for caricature, becoming “the bane of teachers and the delight of her classmates,” she recalled later in an autobiographical essay for The Nation. She taught school in rural Maine just long enough to save up money to enroll at the Massachusetts Normal Art School (now the Massachusetts College of Art and Design) in Boston.

Rogers’ college fund lasted for a year and a half, but she admitted to the Daily Sun reporter that she was not a very disciplined student:

I don’t remember that I learned much about drawing. The life of the city was far too enthralling to my backwood eyes, people, street happenings, circus parades, were a heap sight more fascinating than trying to draw pots and pans with charcoal.

In Boston Rogers also developed a keen interest in physical culture, an early fitness movement that promoted exercise among the masses. Along with a classmate, she left art school and embarked on what she later called a “tramp adventure,” teaching fitness classes in Chicago and points west. Shortly thereafter she returned east with a single ambition:

I decided to be a cartoonist. I came to New York without a cent and without knowing a soul. I was unskilled. I had not the slightest idea of how to tap the city’s resources. I was certain of only one thing: I would be a cartoonist.

Rogers never liked her given name and already went by Lou, which turned out to be “a tremendous help in the days when editors were so prejudiced they could not see humor in a cartoon if they first saw a feminine name attached.” Before long, Rogers was selling “joke stuff to all sorts of magazines and newspapers and syndicates” (Lewiston Daily Sun 1924).

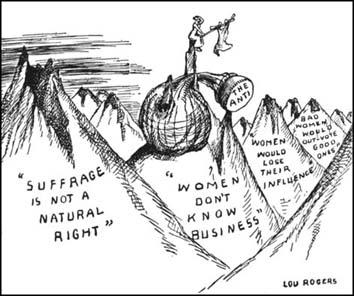

Rogers’ pet issue, unsurprisingly for an independent woman in the 1910s, was women’s suffrage. Around this time she undertook another extraordinary journey, traveling around New York and New Jersey for several months, giving what she called “cartoon speeches” for the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA).

Armed with a folding platform-and-easel contraption built by her brother, she expounded on votes for women while also drawing cartoons “in simple Sunday comic style with a wide, flat grease crayon line, black enough to carry two blocks.” This was “a most thrilling exhausting job,” she told the Sun:

Every ounce of strength one had seemed to be required to hurl the voice into the outskirts of the great crowds that naturally gathered when a woman in an orange smock and cap set up this amazing apparatus….On top of this nervous expenditure the drawing had to be swift and telling and the talk as straight cut as the picture.

Rogers was accustomed to being heckled or even pelted with eggs during her cartoon speeches, but even her detractors were soon captivated by the show since “all people are like little children when it comes to watching a picture grow on a piece of white paper,” she observed (Sheppard 1985).

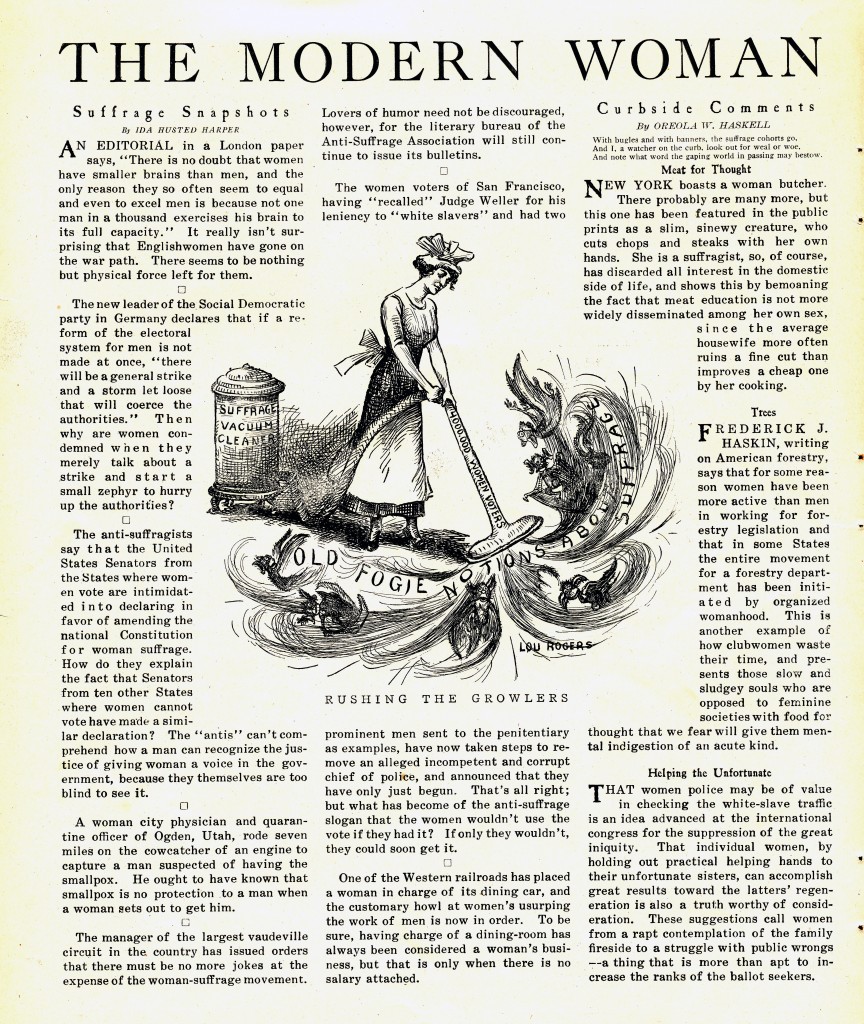

Back in New York City, Rogers landed regular gigs in NWSA’s Woman’s Journal and the New York Call. In 1912, when Judge started a “Modern Woman” page about suffrage issues, Rogers was the main cartoonist. The publication’s art editor Grant Hamilton enthused that “she has what ninety-nine out of a hundred lack, the ability to see the way to get the idea into the picture” (Sheppard 1985).

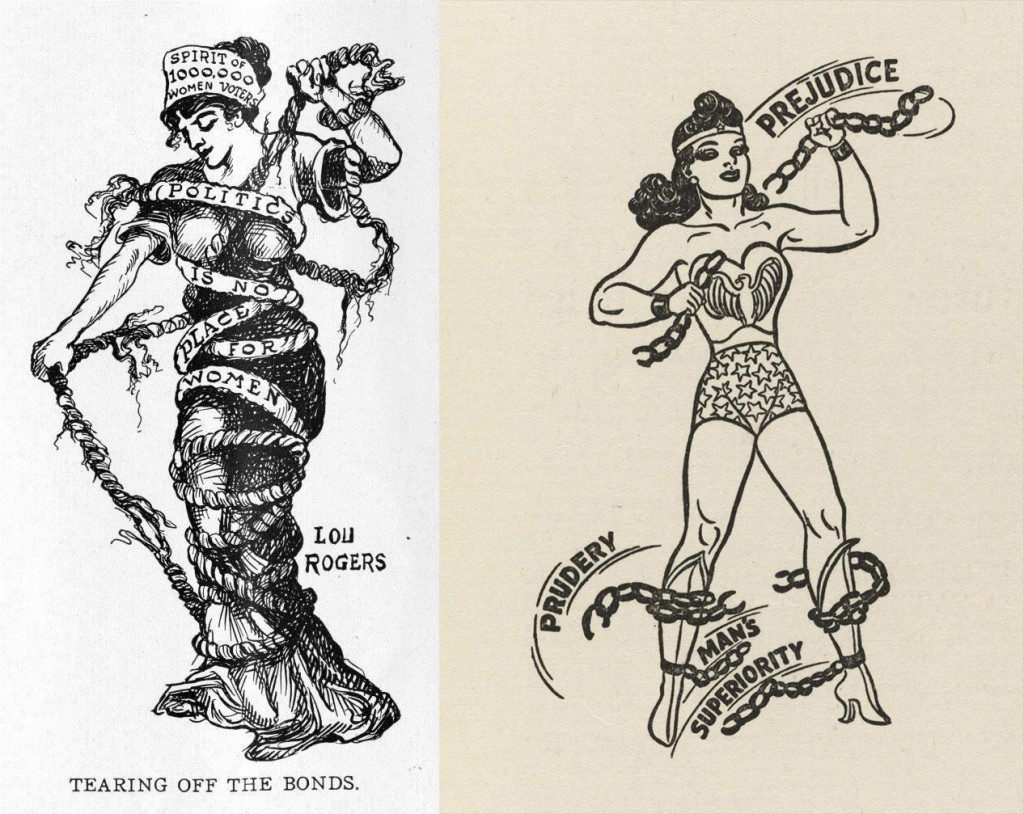

Rogers’ work at Judge may have helped shape one of today’s most popular superheroes (Lepore 2014). While at Judge, Rogers worked alongside Harry George Peter, who would occasionally create pieces for “Modern Woman” when Rogers was overbooked. Peter was the original artist behind William Moulton Marston’s Wonder Woman. Both Marston and Peter were inspired by the suffrage movement in the creation of the character, and while it cannot be determined whether Peter was influenced directly by Rogers work, it still showed the hallmarks of suffrage artwork.

Left: Lou Rogers’ “Tearing Off the Bonds” from the October 19, 1912, issue of Judge. Right: An early H.G. Peter drawing of Wonder Woman (c. 1943).

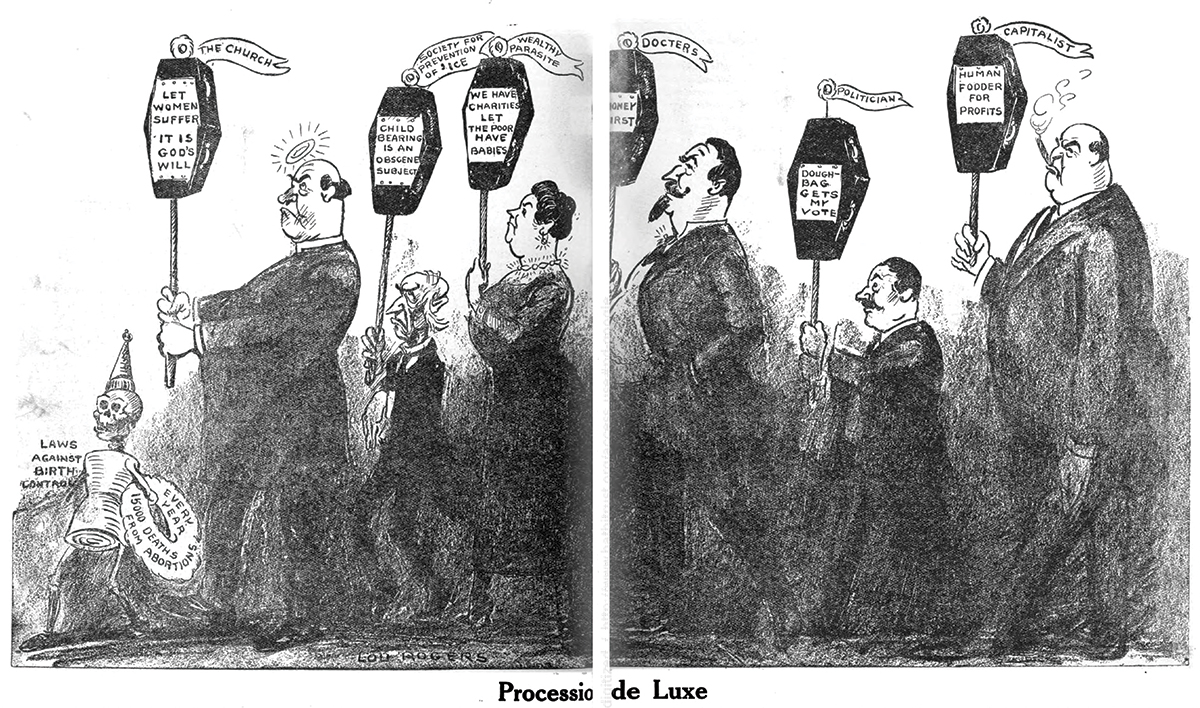

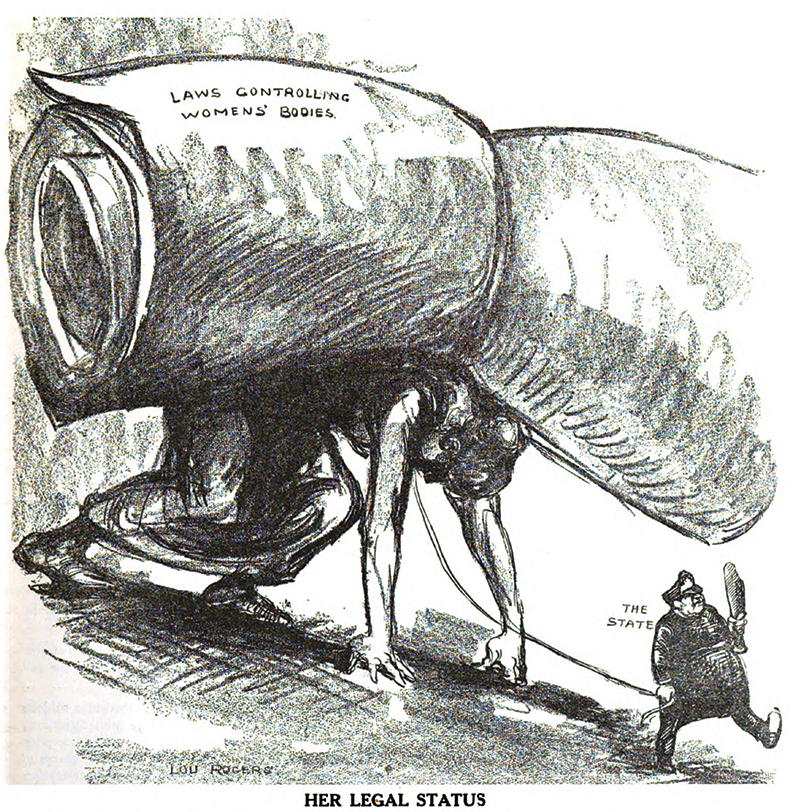

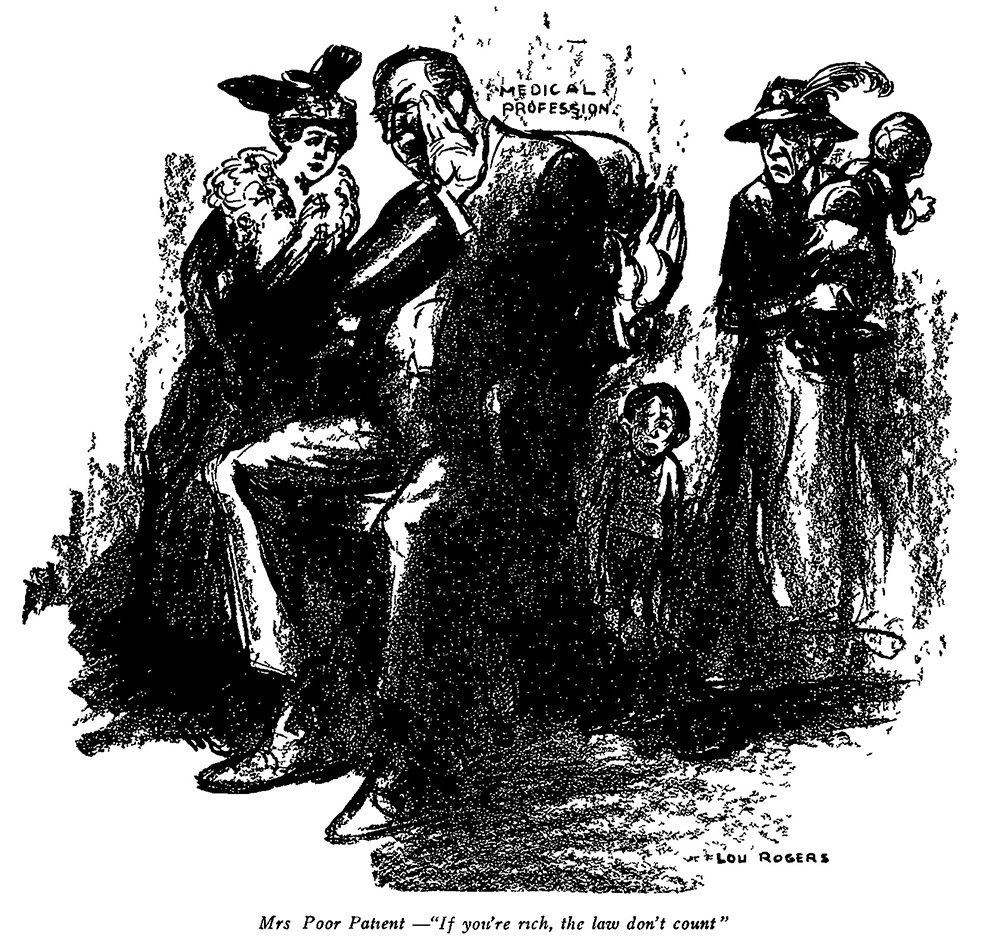

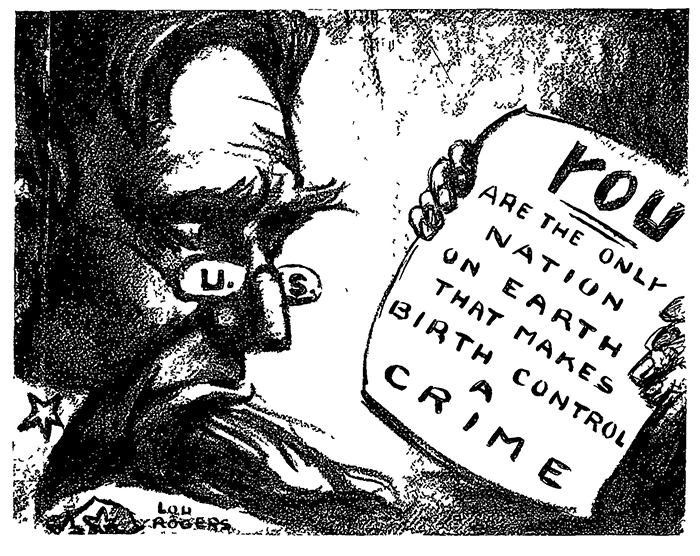

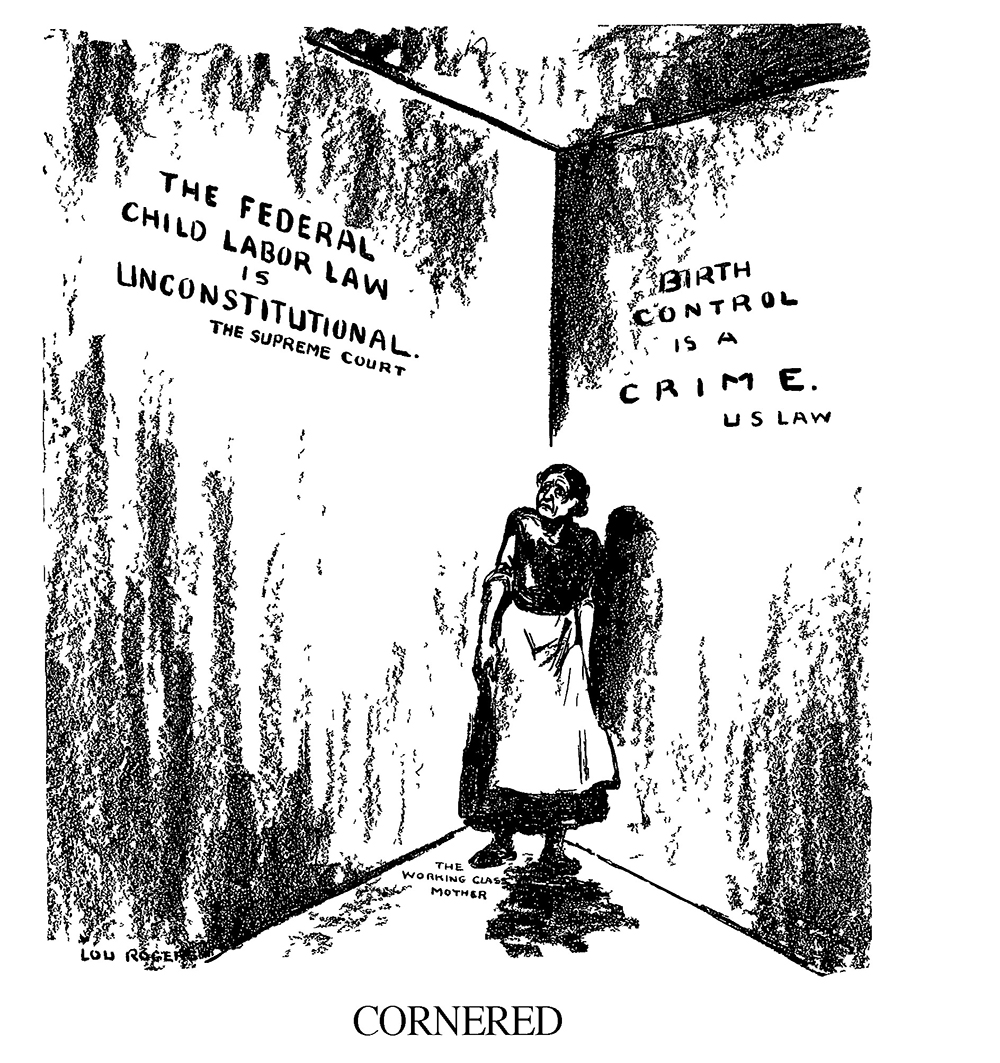

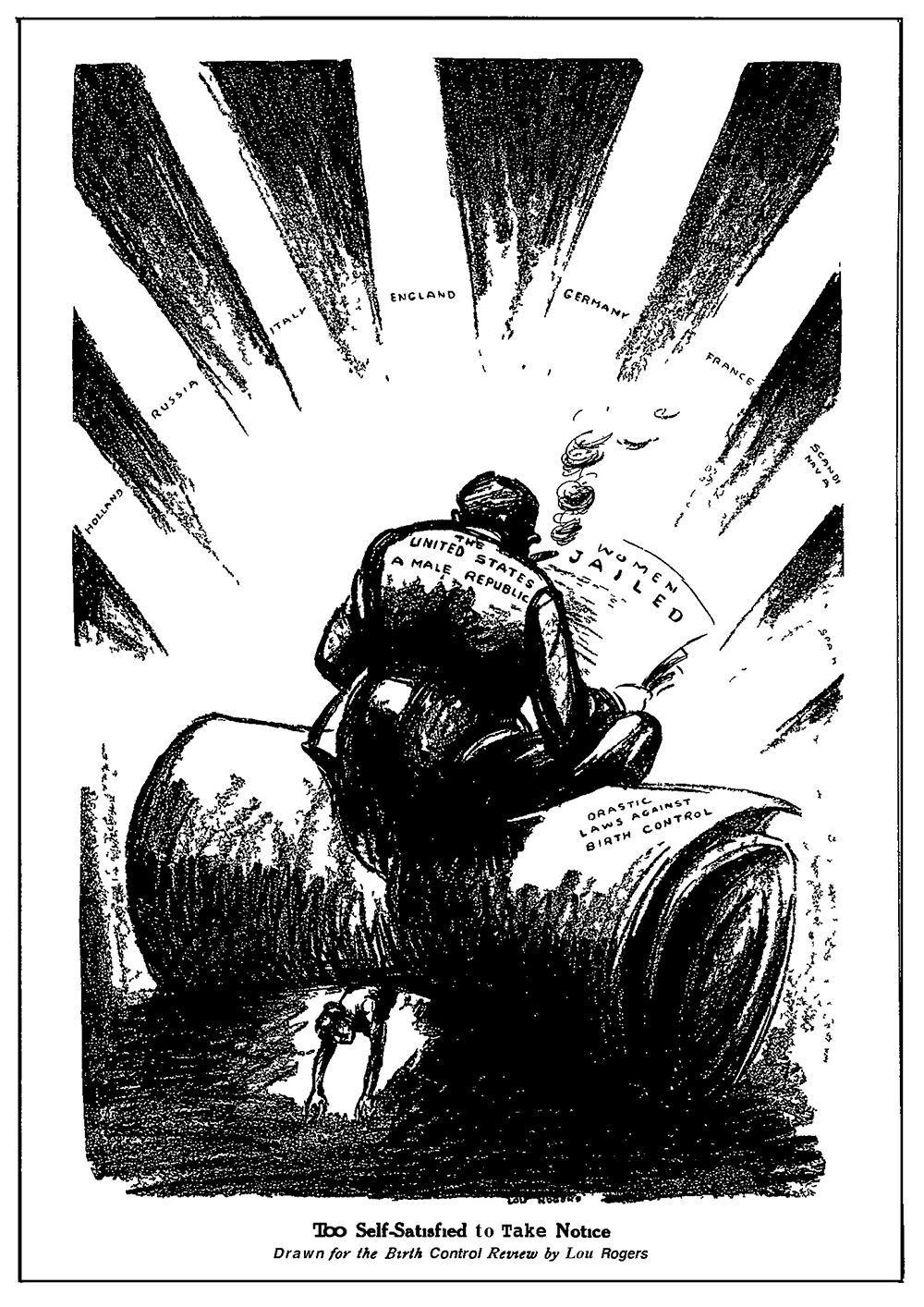

Rogers’ devotion to feminist causes wasn’t limited to the 19th Amendment. In 1918 she joined Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Review as one of three art editors. Birth control was legal in the U.S. for much of the 19th century, but the 1873 Comstock Act had made contraception and the dissemination of information about birth control illegal. Sanger published Birth Control Review in violation of the act, and Rogers contributed spot art, full-page cartoons, and spreads to the publication.

(Notably, Birth Control Review also had a connection to Wonder Woman’s creator: Margaret Sanger was aunt to Marston’s live-in mistress Olive Bryne. Sanger and her sister Ethel Byrne — Olive’s mother — opened the first family planning and birth control clinic in New York in 1916. Both were subsequently arrested for violation of the Comstock Act, and the first issue of Birth Control Review was published in 1917 while Sanger was in jail.)

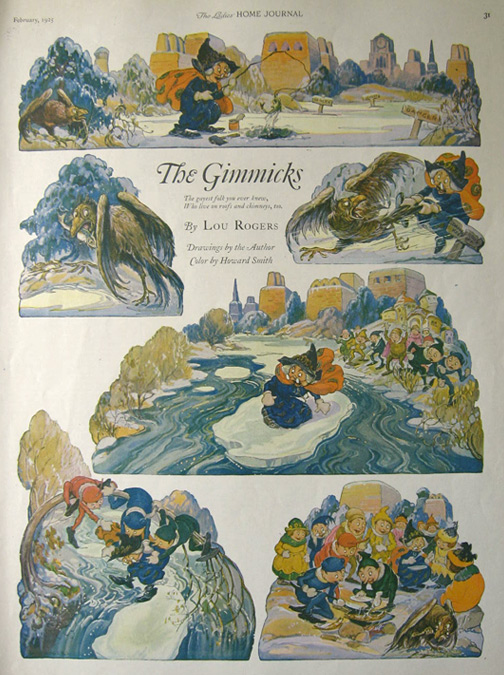

After leaving Birth Control Review in 1922, Rogers created a full-color children’s feature called “The Gimmicks” for Ladies’ Home Journal. Inspired by her fascination with cityscapes that began back in Boston, the Gimmicks were Rogers’ idea of uniquely American elves “with the character that would develop from living up high and around queer roof things” such as drainspouts and fire escapes.

In the 1920s, Rogers married Howard Smith, the colorist for the Gimmicks and some of her later works. For the next several decades, the couple continued to collaborate on illustration projects at their beloved farm near Brookfield, Connecticut. Rogers died of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in 1952 at age 72.

Article by Maren Williams, with contributions from Betsy Gomez. Scans from Birth Control Review via Hathi Trust Digital Library. Wonder Woman is (c) and TM DC Comics.

Learn more about Rogers and other women who changed free expression in comics in CBLDF Presents: She Changed Comics, a resource compiling more than 60 profiles of groundbreaking women creators and featuring interviews with some of the women who are changing the medium today. Get your copy here or read it on comiXology.