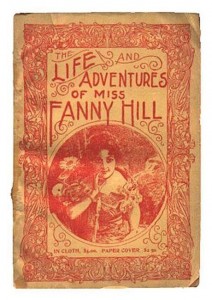

It was a story made for sensational headlines and easy clickbait: Fanny Hill, John Cleland’s 1748 faux memoir of a London prostitute, was supposedly banned at a modern British university for fear of offending delicate millennial students. But close on the heels of the initial reports came a detailed rebuttal from the professor and alleged censor, arguing that media outlets were twisting reality in their haste to stereotype today’s youth as “snowflakes” who demand trigger warnings at every turn. Where does the truth lie?

It was a story made for sensational headlines and easy clickbait: Fanny Hill, John Cleland’s 1748 faux memoir of a London prostitute, was supposedly banned at a modern British university for fear of offending delicate millennial students. But close on the heels of the initial reports came a detailed rebuttal from the professor and alleged censor, arguing that media outlets were twisting reality in their haste to stereotype today’s youth as “snowflakes” who demand trigger warnings at every turn. Where does the truth lie?

The university in question is Royal Holloway, University of London, and the professor is Judith Hawley, who teaches a course called The Age of Oppositions: Literature, 1660-1780. Based on an offhand remark that she made on a recent BBC Radio 4 series about the history of free speech, British Vogue erroneously reported on its website that Hawley had removed Fanny Hill from the course reading list. In fact, she later clarified in a column for The Guardian, the novel simply never was a part of that particular course.

The confusion arose from the fact that Hawley did teach the book in other courses during the 1980s, an era when she felt “it seemed important to make sure that the issues raised by Fanny Hill, including desire, pornography and power, were discussed in an academic environment.” Since that time, both the literary-historical canon and the student body have diversified somewhat, and Hawley feels that other works “including erotic poems by Rochester and Aphra Behn” now lead to more fruitful analysis. In fact she points out that for today’s students, pornography is ubiquitous and the raunchy Fanny Hill no longer holds the same power to shock.

It is not outside the realm of possibility that Cleland’s epistolary novel could be censored, of course; it was the subject of an early U.S. obscenity trial in 1821 and again in 1966, when the Supreme Court overturned Massachusetts’ ban on the book in the landmark case Memoirs v. Massachusetts. (Benjamin Franklin is believed to have owned a copy of the particularly salacious illustrated edition at issue in the earlier case.)

This long and distinguished history apparently made Hawley’s alleged ban of the book both believable and irresistible for British media, especially those looking to advance the narrative that millennials are uniformly coddled and unwise to the ways of the world. But while Hawley said that she has occasionally had students request trigger warnings on reading lists, their naïveté has been greatly exaggerated in the popular imagination:

Universities encourage students to question what they learn and to participate actively in their education. Discussions about the curriculum are a normal part of that process. What seems important is a commitment on all sides to the free exchange of ideas in a critical debate. A climate of suspicion may be growing on our campuses – but it is fostered in sensational headlines about banning books.

In 2015, a survey commissioned by the National Coalition Against Censorship reached similar conclusions for U.S. higher education: trigger warnings and student requests for them are real, but they’re not yet at the epidemic level that has often been depicted in media–particularly not at public institutions. This is certainly an issue that warrants public discussion and debate, but that goal is not accomplished when media outlets simply jump on the millennial-bashing bandwagon.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2017 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.