To wind up our Women Who Changed Free Expression series that ran throughout March, CBLDF Advisory Board member and Mechademia co-founder Frenchy Lunning provided this compendium of the female creators who transformed the manga landscape in the late 1960s. All our thanks to Frenchy!

The 24 nengumi: The Female Progenitors of Shôjo Manga

Year 24 Group, also known as the Forty-Niners or the 24 nengumi (24年組 Nijūyo-nen Gumi) because most were born in Shōwa 24 (1949), refers to the first of two key groups of extraordinary female mangaka, considered to have innovated, created, and revolutionized the category we now celebrate as ‘shōjo manga.’ As Matt Thorn states, in the 1950s and early 1960s:

Year 24 Group, also known as the Forty-Niners or the 24 nengumi (24年組 Nijūyo-nen Gumi) because most were born in Shōwa 24 (1949), refers to the first of two key groups of extraordinary female mangaka, considered to have innovated, created, and revolutionized the category we now celebrate as ‘shōjo manga.’ As Matt Thorn states, in the 1950s and early 1960s:

the majority of shôjo manga were created by male artists, most of whom also worked in the shônen genre. The number of professional women artists working in shôjo manga prior to 1960 (most notably, Toshiko Ueda, Masako Watanabe, Hideko Mizuno, and Miyako Maki) could almost be counted on the fingers of one hand. The stories featured primary school girls, and generally fell into one of three categories: humor, horror, or tear-jerker. Mother-daughter relationships featured prominently, and boy-meets-girl stories were still relatively rare, which is not surprising considering the tender age of the heroines (and readers).1

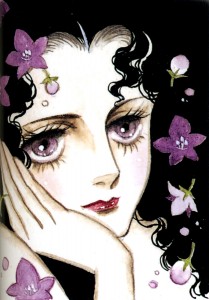

These young women significantly contributed to the development of a radical family of subgenres in shōjo manga,and marked the first major point of artistic and narrative injection for women artists into manga, and also into comics globally. It became a category that was overwhelmingly influenced by feminist concerns, and has expanded to include a compelling host of queer categories, conceived, created, and drawn primarily by women artists for an audience specifically of girls and young women. Among the innovations to be found in shōjo manga are emotion-driven panel layouts, where shifting temporal and fantastical elements introduce manpu of feathers, flowers, puffy clouds, and twinkling stars all in aid of the narrative process. Their works often examine radically queer issues, including sexuality, gender, and transgender issues, and many of those works are now considered “classics” of shōjo manga.

Note: This list was created by gleaning their stories from various online sources, reflecting the chance and accidental quality of contemporary digital research, and the permeation of the notion of the ‘urban legend’ lending its own disputable form of ‘credibility.’ However, since most of these works clearly seem to have heavily mined the work of Matt Thorn, it represents something close to a primary source, as he seems to have known and interviewed many of these remarkable women.

Yasuko Aoike – Most of her works are shōjo manga, focused on the feminine categories of romance, adventure, and light comedy, but also contain elements of shōnen-ai (“beautiful boy”) as part of the queer phenomenon. She made her professional debut in the Ribon magazine 1963 Winter Special Edition with the short story Sayonara Nanette. Many of her short works appeared in Shôjo Friend and other Kodansha publications through the mid-1970s. She began writing serial works primarily for Akita Shoten, a Japanese manga publisher focusing on shōjo and shōnen manga, starting with Miriam Blue’s Lake in the January 1975 issue of Princess. Her works El Alcon, Seven Seas,and Seven Skies also appeared in Shueisha‘s version of Seventeen Magazine in the late 1970s, and Hakusensha‘s Lala magazine in the 1980s. She is best known for From Eroica with Love, which was serialized by Akita Shoten beginning in 1976 and produced several spinoff series.2

Yasuko Aoike – Most of her works are shōjo manga, focused on the feminine categories of romance, adventure, and light comedy, but also contain elements of shōnen-ai (“beautiful boy”) as part of the queer phenomenon. She made her professional debut in the Ribon magazine 1963 Winter Special Edition with the short story Sayonara Nanette. Many of her short works appeared in Shôjo Friend and other Kodansha publications through the mid-1970s. She began writing serial works primarily for Akita Shoten, a Japanese manga publisher focusing on shōjo and shōnen manga, starting with Miriam Blue’s Lake in the January 1975 issue of Princess. Her works El Alcon, Seven Seas,and Seven Skies also appeared in Shueisha‘s version of Seventeen Magazine in the late 1970s, and Hakusensha‘s Lala magazine in the 1980s. She is best known for From Eroica with Love, which was serialized by Akita Shoten beginning in 1976 and produced several spinoff series.2

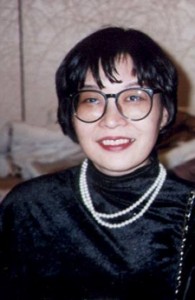

Moto Hagio –She is considered a “founding mother” of modern shōjo manga, especially shōnen-ai. She has been described as “the most beloved shōjo manga artist of all time,” by Matt Thorn and others. In addition to being a creative pioneer, her body of work was one of the first of the emerging shōjo genre and shows a remarkable maturity, psychological depth, a poignant gift for storytelling, and a unique personal vision, setting the standard for the mangaka of all genders to follow. Moto Hagio made her professional debut in 1969 at the tender age of 20 with her short story “Lulu to Mimi” in Nakayoshi. Two years after her debut, she published Juichigatsu no Gimunajiumu 11月のギムナジウム (The November Gymnasium), a stunning short story that dealt openly with the homosexual love between two young boys at a boarding school, the first emergence in a larger movement generated by female mangaka that pioneered shōnen-ai, a genre of girls’ comics about love between young men. These stories became a major genre for the feminist-oriented mangaka of the 24 nengumi. In 1974, Hagio developed this story into the longer and famous manga, Thomas no Shinzō (The Heart of Thomas). She was awarded the Shogakukan Manga Award in 1976 for her science fiction classic Juichinin Iru! (They Were Eleven) and her epic tale Poe no Ichizoku (The Poe Family). In the mid-1980s, Hagio wrote her first long work – Marginal. Prior to writing Iguana Girl in 1991, Hagio had not set her works in contemporary Japan. She is still actively working in manga.3

Moto Hagio –She is considered a “founding mother” of modern shōjo manga, especially shōnen-ai. She has been described as “the most beloved shōjo manga artist of all time,” by Matt Thorn and others. In addition to being a creative pioneer, her body of work was one of the first of the emerging shōjo genre and shows a remarkable maturity, psychological depth, a poignant gift for storytelling, and a unique personal vision, setting the standard for the mangaka of all genders to follow. Moto Hagio made her professional debut in 1969 at the tender age of 20 with her short story “Lulu to Mimi” in Nakayoshi. Two years after her debut, she published Juichigatsu no Gimunajiumu 11月のギムナジウム (The November Gymnasium), a stunning short story that dealt openly with the homosexual love between two young boys at a boarding school, the first emergence in a larger movement generated by female mangaka that pioneered shōnen-ai, a genre of girls’ comics about love between young men. These stories became a major genre for the feminist-oriented mangaka of the 24 nengumi. In 1974, Hagio developed this story into the longer and famous manga, Thomas no Shinzō (The Heart of Thomas). She was awarded the Shogakukan Manga Award in 1976 for her science fiction classic Juichinin Iru! (They Were Eleven) and her epic tale Poe no Ichizoku (The Poe Family). In the mid-1980s, Hagio wrote her first long work – Marginal. Prior to writing Iguana Girl in 1991, Hagio had not set her works in contemporary Japan. She is still actively working in manga.3

Riyoko Ikeda –Ikeda has written and illustrated many shōjo manga, most of which are based on actual historical events, such as the French and Russian Revolutions. Her “use of foreign settings and androgynous themes made The Rose of Versailles and Orpheus no Mado ‘enormous successes.’ Perhaps the most famous manga of the last century, is The Rose of Versailles also known as Lady Oscar in Europe. This manga, loosely based on the French Revolution, has been made into several Takarazukamusicals and into an anime series and a live-action film. After Rose of Versailles concluded, Ikeda wrote articles for Asahi Shimbun . . . Her recent manga includes Der Ring des Nibelungen. It is a manga version of the opera written by Richard Wagner.”4

Riyoko Ikeda –Ikeda has written and illustrated many shōjo manga, most of which are based on actual historical events, such as the French and Russian Revolutions. Her “use of foreign settings and androgynous themes made The Rose of Versailles and Orpheus no Mado ‘enormous successes.’ Perhaps the most famous manga of the last century, is The Rose of Versailles also known as Lady Oscar in Europe. This manga, loosely based on the French Revolution, has been made into several Takarazukamusicals and into an anime series and a live-action film. After Rose of Versailles concluded, Ikeda wrote articles for Asahi Shimbun . . . Her recent manga includes Der Ring des Nibelungen. It is a manga version of the opera written by Richard Wagner.”4

Yumiko Ōshima –She made her debut in 1968 with “Paula’s Tears” in the Weekly Margaret. She received the 1978 Kodansha Manga Award for shōjo for her work The Star of Cottonland,and the 2008 Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize Short Story Award for Gû-gû date Neko de aru. She is credited with popularizing the kemonomimi (catgirl) of Chibi-neko inThe Star of Cottonland. This is a character type of her creation: an innocent, child-like character, rather than the current icon of the sexy aggressive cat-girl. She approaches profound and disturbing issues in eccentric ways, taking the reader into realms that are unfamiliar and even uncanny.5

Yumiko Ōshima –She made her debut in 1968 with “Paula’s Tears” in the Weekly Margaret. She received the 1978 Kodansha Manga Award for shōjo for her work The Star of Cottonland,and the 2008 Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize Short Story Award for Gû-gû date Neko de aru. She is credited with popularizing the kemonomimi (catgirl) of Chibi-neko inThe Star of Cottonland. This is a character type of her creation: an innocent, child-like character, rather than the current icon of the sexy aggressive cat-girl. She approaches profound and disturbing issues in eccentric ways, taking the reader into realms that are unfamiliar and even uncanny.5

Keiko Takemiya –Takemiya has explored a variety of stories and themes, ranging from high school romances to boys love, historical dramas and hard sci-fi. Besides winning numerous awards for To Terra (Terra e, a.k.a. Toward the Terra), Takemiya is most notably credited as one of the key creators of the now hugely popular “Boys Love”/”BL” / yaoi manga genre with her 1976 story, Song of the Wind and Trees (Kaze to Ki no Uta) and as a founding force behind June, a Japanese “Boys Love” anthology magazine. Since 2000, Takemiya has been a professor at Kyoto Seika University; furthermore, with Vertical’s recent publication of her sci-fi epics To Terra and Andromeda Stories in English, more readers than ever are being introduced to the work of this manga pioneer and innovator.6

Keiko Takemiya –Takemiya has explored a variety of stories and themes, ranging from high school romances to boys love, historical dramas and hard sci-fi. Besides winning numerous awards for To Terra (Terra e, a.k.a. Toward the Terra), Takemiya is most notably credited as one of the key creators of the now hugely popular “Boys Love”/”BL” / yaoi manga genre with her 1976 story, Song of the Wind and Trees (Kaze to Ki no Uta) and as a founding force behind June, a Japanese “Boys Love” anthology magazine. Since 2000, Takemiya has been a professor at Kyoto Seika University; furthermore, with Vertical’s recent publication of her sci-fi epics To Terra and Andromeda Stories in English, more readers than ever are being introduced to the work of this manga pioneer and innovator.6

Toshie Kihara –She made her professional debut in 1969 with Kotchi muite Mama! in Bessatsu Margaret, and has continued to write in mainly historical and shōnen-ai manga. She is best known for her series Mari to Shingo (published in Hana to Yume from 1979–1984) about a romance between two young men in the early Shōwa era. She received the 1985 Shogakukan Manga Award for shōjo for Yume no Ishibumi, short stories with shōnen-ai themes. Still working in 1998, Kihara adapted Torikaebaya Monogatari, a Heian-era tale, into a manga volume called Torikaebaya Ibun, which was thereafter adapted as a Takarazuka Revue musical.7

Ryoko Yamagishi – In 1966, Yamagishi began as a semi-finalist in a competition in Shōjo Friend, then applied to Kodansha and COM, and ultimately in 1968, applied to Shuiesha, finally making her debut with left< And >right (レフトアンドライト), in Ribon. In 1983, she won the Kodansha Manga Award for shōjo manga for Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi. In 2007 she won the Grand Prize for the 11th Annual Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize for Terpsichora (The Dancing Girl; Maihime Τερψιχόρα). Her works normally have occult themes, although her most popular are her ballet manga, Arabesque about Russian ballet, and Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi. According to Yoshihiro Yonezawa, Yamagishi’s style is influenced by Art Nouveau.8

Ryoko Yamagishi – In 1966, Yamagishi began as a semi-finalist in a competition in Shōjo Friend, then applied to Kodansha and COM, and ultimately in 1968, applied to Shuiesha, finally making her debut with left< And >right (レフトアンドライト), in Ribon. In 1983, she won the Kodansha Manga Award for shōjo manga for Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi. In 2007 she won the Grand Prize for the 11th Annual Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize for Terpsichora (The Dancing Girl; Maihime Τερψιχόρα). Her works normally have occult themes, although her most popular are her ballet manga, Arabesque about Russian ballet, and Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi. According to Yoshihiro Yonezawa, Yamagishi’s style is influenced by Art Nouveau.8

Minori Kimura – She made her professional debut in 1964 at the tender age of 14 with her story Picnic, serialized in the Spring Special issue of Ribon. She continued writing stories during her school breaks that were published in magazines such as COM and Ribon Comic. During the 1960s and early 1970s, she addressed political and historical issues through stories around places like Auschwitz, Vietnam, and the slums of Rio de Janeiro. After college, she took a short break from publishing before returning with Gift (贈り物 Okurimono), published by Shogakukan in Bessatsu Shōjo Comic in 1974. The story discussed the struggles of elementary school life. She then published This Side of the Rape Blossom Field (菜の花畑のこちら側 Nanohana Hatake no Kochiragawa), the story of four young college girls living together. This story caused her to gain popularity, and from that point she generally published in shōjo, seinen, and ladies manga magazines from Akita Shoten and Kodansha.9

Nanae Sasaya –Nanaeko Sasaya teaches at Kyoto Seika University’s cartoon art department. She grew up loving Leiji Matsumoto’s comics for girls, including Maria of the Silver Valley and Forest of Luna, and was herself inspired by the work of Shotaro Ishinomori. Her debut work, Seagull, was published in Ribon, January 1970 issue. In 1982 she was one of the contributors to ANIDO’s Gekkan Betty, a one-shot magazine. In 1990, she won an Excellence Prize at the Japanese Cartoonists’ Association awards for “Superior Observation by an Outsider.” In 1996 she changed her personal name to Nanaeko, and drew Frozen Eyes, a searing tale of child sexual abuse written by Atsuko Shiina, which caused considerable controversy and had a follow-up series in 2003. Her works embrace the uncanny horrors of everyday life, in addition to suspense, black comedy, and offbeat romances with a sinister twist, and compromised relationships.10

Nanae Sasaya –Nanaeko Sasaya teaches at Kyoto Seika University’s cartoon art department. She grew up loving Leiji Matsumoto’s comics for girls, including Maria of the Silver Valley and Forest of Luna, and was herself inspired by the work of Shotaro Ishinomori. Her debut work, Seagull, was published in Ribon, January 1970 issue. In 1982 she was one of the contributors to ANIDO’s Gekkan Betty, a one-shot magazine. In 1990, she won an Excellence Prize at the Japanese Cartoonists’ Association awards for “Superior Observation by an Outsider.” In 1996 she changed her personal name to Nanaeko, and drew Frozen Eyes, a searing tale of child sexual abuse written by Atsuko Shiina, which caused considerable controversy and had a follow-up series in 2003. Her works embrace the uncanny horrors of everyday life, in addition to suspense, black comedy, and offbeat romances with a sinister twist, and compromised relationships.10

Mineko Yamada –She made her debut in 1969 with “Haru no Uta.” In the 1970s, she began to draw for Margaret, then for Hana to Yuma and eventually for Lala. Her most popular series is Harmageddon. In the 1990s she also began to write novels. Currently she has withdrawn from working in manga forms, except for some dojinshi-titles.11

1. Matt Thorn, “A History of Manga,” a revision of which was first published in three installments in Animerica: Anime & Manga Monthly, Volume 4, Numbers 2, 4 & 6 (February, April & June, 1996). http://www.matt-thorn.com/mangagaku/history.html↩

2. “Yasuko Aoike,” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 Dec. 2014. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yasuko_Aoike↩

3. “Moto Hagio,” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 Dec. 2015, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moto_Hagio↩

4. “Riyoko Ikeda,” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 March, 2015, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Riyoko_Ikeda↩

5. “Ôshima Yumiko,” Baka Up-dates: Manga, 8 April, 2014. https://www.mangaupdates.com/authors.html?id=4537↩

6. Deb Aoki, “Interview: Keiko Takemiya,” About Entertainment, http://manga.about.com/od/mangaartistswriters/a/KeikoTakemiya.htm↩

7. “KIHARA Toshie,” Baka-Updates: Manga, 21 Sept. 2014, https://www.mangaupdates.com/authors.html?id=4134↩

8. “Ryoko Yamagishi,”Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 23 Nov. 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryoko_Yamagishi↩

9. Minori Kimura, Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 16 Nov. 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minori_Kimura↩

10. Helen McCarty, “Unknown in English 4: Nanaeko Sasaya,” Helen McCarty: A Face Made for Radio, 20 June, 2010, https://helenmccarthy.wordpress.com/2010/06/20/unknown-in-english-4-nanaeko-sasaya/↩

11. “Yamada, Mineko,” MyAnimeList, http://myanimelist.net/people/7376/Mineko_Yamada↩