James Augusta Aloysius Joyce is considered to be one of the most influential writers of the early 20th century. His book Ulysses has been called one of the most challenging and rewarding novels ever written and is considered to be one of the most important works of Modernist literature. However, what many may not realize is that the book was also the subject of litigation that led to a major change in the way the courts analyzed obscenity cases and expanded the First Amendment rights of authors. This is the story of United States v. One Book Called “Ulysses.”

James Augusta Aloysius Joyce is considered to be one of the most influential writers of the early 20th century. His book Ulysses has been called one of the most challenging and rewarding novels ever written and is considered to be one of the most important works of Modernist literature. However, what many may not realize is that the book was also the subject of litigation that led to a major change in the way the courts analyzed obscenity cases and expanded the First Amendment rights of authors. This is the story of United States v. One Book Called “Ulysses.”

Ulysses tells the story of a Leopold Bloom and a tortured artist named Stephen. Each of the 18 chapters (or episodes) describe and relate a series of encounters and incidents that occur as Bloom travels through Dublin on June 16, 1904. (It should be noted the dates is significant because it marks Joyce’s first date with his future wife, Nora Barnacle). Joyce intentionally paralleled the characters and events in the Odyssey, the epic poem written by Homer. In fact, the name Ulysses is the Latin form of the name of Odysseus, the star of the Odyssey.

Ulysses was released in serialized form in the American journal The Little Review from March 1918 to December 1920. However, the book came under fire after the release of Episode 13, (later entitled “Nausicaa”), which features a story in which Bloom watches and fantasizes about a young woman named Gerty MacDowell as he pleasures himself. Bloom climaxes just as fireworks explode at a nearby bazaar. After the release of this episode, which also contained some profanity, the United States Post Office determined the material was obscene and confiscated three issues of The Little Review, burning 500 copies of them.

After a girl of unknown age read the book, a complaint was filed with the Manhattan District Attorney’s office (the book was sold in Manhattan, which was the primary place of business for The Little Review). After a 1921 trial that was initiated by The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, the magazine was declared obscene. As a result, the publishers of The Little Review, Margaret Caroline Anderson and Jane Heap, were fined $50.00 each (about $700 today when adjusted for inflation) and were almost sentenced to prison. Interestingly, during the trial, the court refused to allow certain passages of the book to be read aloud because there were women present. Ironically, the only women present were, in fact, the publishers of the book. The court further rejected the expert testimony that praised the book as a work of art and held that Ulysses appeared “like the work of a disorganized mind.” As a result of this ruling, Ulysses was effectively banned in the United States.

(I should add that, although excerpts of Ulysses also appeared in the London literary journal named The Egois, the novel itself was banned in the United Kingdom until the 1930s.)

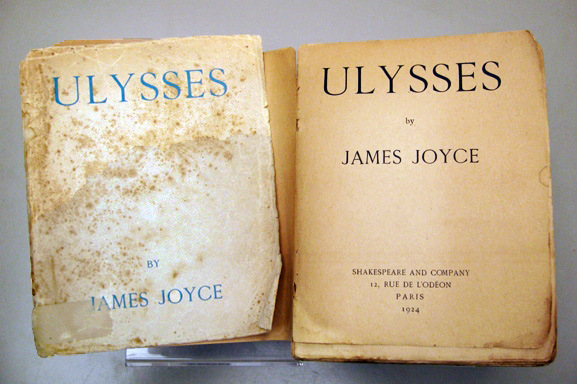

In 1922, the entirety of Ulysses was published by the Parisian publisher Sylvia Beach, who also owned the bookstore Shakespeare and Company. The book became an instant hit and was frequently smuggled into the United States and Britain as a guilty pleasure. In 1928, the United States Customs Court officially included Ulysses on the list of prohibited obscene books under the Tariff Act of 1930, which meant that the book could not be brought legally into the United States. This only increased the book’s popular and critical acclaim.

After several noted writers of the day — the likes of T.S. Elliot, Virginia Wolf, and Ezra Pound — praised the book, Bennett Cerf, cofounder of Random House with Donald S. Klopfer, became interested in bringing Ulysses to America, which meant it needed to be removed from the obscene list.

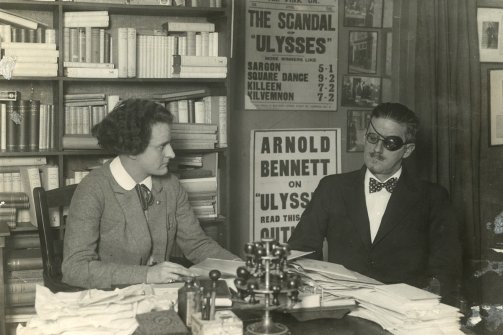

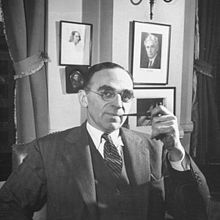

To do this, Cerf turned to Morris L. Ernst, the world’s leading authority on obscenity (pictured right). In what many consider an unorthodox payment scheme, Ernst was paid on a contingency fee of a five percent of the first 10,000 copies of Ulysses published and then a two percent payment for all subsequent books published over Cerf’s life.

To do this, Cerf turned to Morris L. Ernst, the world’s leading authority on obscenity (pictured right). In what many consider an unorthodox payment scheme, Ernst was paid on a contingency fee of a five percent of the first 10,000 copies of Ulysses published and then a two percent payment for all subsequent books published over Cerf’s life.

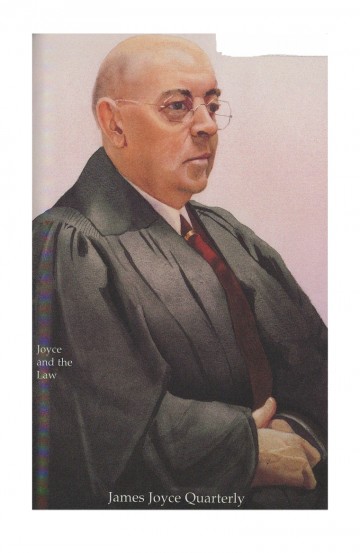

Ernst devised a plan in which the book would be confiscated by Customs, allowing Cerf to file suit under the provisions of the Tariff Act of 1930. Ernst’s trial strategy was simple: He wanted the case to be heard by a judge and not a jury, who might be shocked by the language. But Ernst did not seek just any judge. He kept postponing the case until it could be heard by Judge John M. Woolsey (pictured left), who had a reputation for being a lover of old books and took the time to write poetic decisions. Cerf most likely knew that his strategy paid off when Judge Woolsey postponed the trial to give him time to not only read Ulysses in its entirety, but to also read several critical essays and books that had been written about Ulysses.

Ernst devised a plan in which the book would be confiscated by Customs, allowing Cerf to file suit under the provisions of the Tariff Act of 1930. Ernst’s trial strategy was simple: He wanted the case to be heard by a judge and not a jury, who might be shocked by the language. But Ernst did not seek just any judge. He kept postponing the case until it could be heard by Judge John M. Woolsey (pictured left), who had a reputation for being a lover of old books and took the time to write poetic decisions. Cerf most likely knew that his strategy paid off when Judge Woolsey postponed the trial to give him time to not only read Ulysses in its entirety, but to also read several critical essays and books that had been written about Ulysses.

The main issue in the case was whether Joyce’s intent in writing Ulysses was obscene. At the time, the prevailing view of obscenity was based on an 1868 English case called Regina v. Hicklin, in which the court defined obscenity as material that corrupted “those whose minds are open to … immoral influences” and that led to “the young … thoughts of a most impure and libidinous character.” In short, up until the second Ulysses trial, courts looked to how children would view the material to support anti-obscenity laws, regardless of the age of the intended audience.

With this standard in mind, the government had two primary arguments in the Ulysses trial. First, the book contained profanity. Once again, the prosecutor attempted to shock the Court by claiming that it “couldn’t win” because he did not want to “refer to the great number of vulgar four letter words used by Joyce … [b]ecause there was a lady in the courtroom.”

In response, the experienced litigator Ernst quickly pointed out that the woman was his wife, a school teacher. “She’s seen all these words on toilet walls or scribbled on sidewalks by kids who enjoy them because of their being taboo.” Instead, Ernst argued that the language was necessary to convey the author’s true intent. For example, Ernst pointed to the fact that one such controversial expletive had “more honesty than [when modern authors say] they slept together.” He added, “It means the same thing.”

Ernst knew the battle was almost won, when the judge corrected him and said, “That isn’t usually even the truth.”

The government’s second argument related to the directness of the language contained in the book as related to the women in the book. In addition to the Gerty MacDowell scenes in Episode 13, Ulysses also included Molly Bloom’s Soliloquy in Episode 18, which consists of the stream of consciousness thoughts of Leopold’s wife as she lays next to him in bed. The soliloquy consists of eight run-on sentences without punctuation. The episode, along with the book, ends with:

…I was a Flower of the mountain yes when I put the rose in my hair like the Andalusian girls used or shall I wear a red yes and how he kissed me under the Moorish wall and I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.

During the trial, Judge Woolsey asked Ernst if he had read the entire book. Ernst replied:

Yes, Judge, I tried to read it in 1923 but could not get far into it. Last summer, I had to read it in preparation for this trial. And while lecturing in the Unitarian Church in Nantucket on the bank holiday.…

The court, annoyed, interrupted, “What has that to do with my question — have you read it?” Ernst ignored the interruption and continued,

While talking in that church I recalled after my lecture was finished that while I was thinking only about the banks and the banking laws, I was in fact, at that same time, musing about the clock at the back of the church, the old woman in the front row, the tall shutters at the sides. Just as now, Judge, I have thought I was involved only in the defense of the book — I must admit at the same time I was thinking of the gold ring around your tie, the picture of George Washington behind your bench and the fact that your black judicial robe is slipping off your shoulders. This double stream of the mind is the contribution of Ulysses.

The court was persuaded. Judge Woolsey said,

Now for the first time I appreciate the significance of this book. I have listened to you as intently as I know how. I am disturbed by the dream scenes at the end of the book, and still I must confess, that while listening to you, I have been thinking at the same time about the Hepplewhite furniture behind you.

Ernst pressed his advantage and argued, “Judge, that’s the book.”

The prosecutors next pointed to the fact that the racier sections of the book, when read in isolation, were sexually explicit and obscene. They queried the court to consider what would happen if a child found these portions of the text. Ernst dismissed this and argued, “Adult literature [should never] be reduced to mush for infants.”

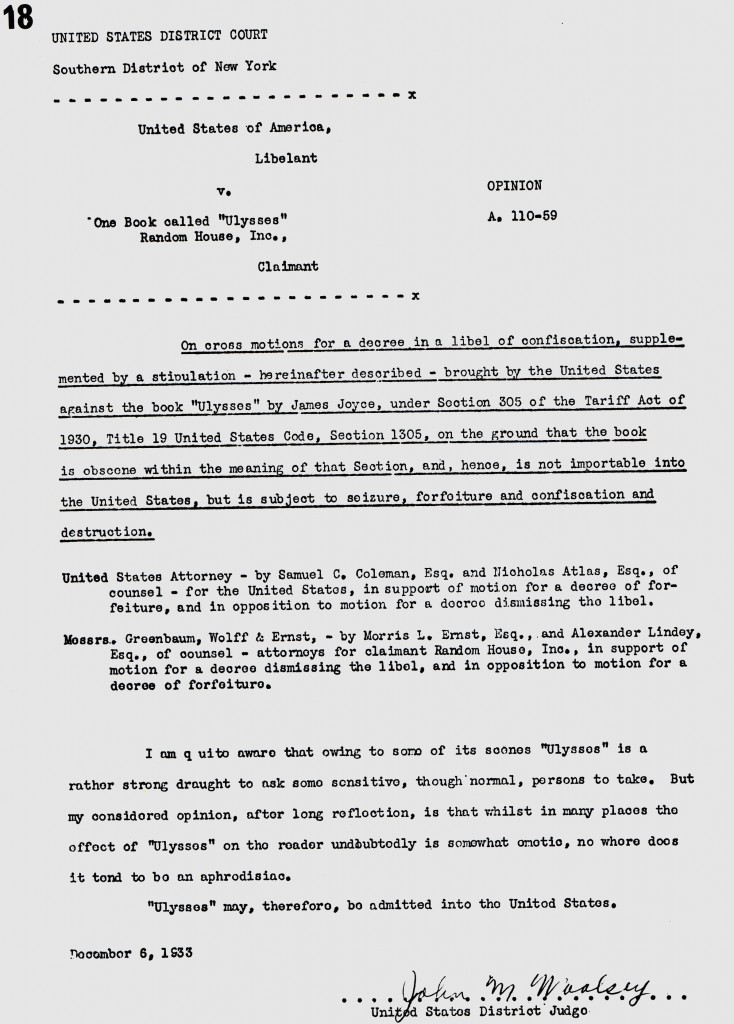

The court issued its opinion on December 6, 1933 and ruled in favor of the book. The court dismissed the government’s motion for forfeiture and destruction and libel.

The court wrote:

I hold that Ulysses is a sincere and honest book … The words which are criticized as dirty are old Saxon words known to almost all men and, I venture, to many women, and are such words as would be naturally and habitually used, I believe by the types of folk whose life, physical and mental, Joyce is seeking to describe. In respect of the recurrent emergence of the theme of sex in the minds of his characters, it must always be remembered that his locale was Celtic and his season Spring.

More importantly, the court did not apply an obscenity standard that deprived adults of literature thought corrupting to children. Instead, the court examined whether the work would “lead to sexually impure and lustful thoughts” in a normal adult. The court wrote:

I am quite aware that owing to some of its scenes Ulysses is a rather strong draught to ask some sensitive, though normal, persons to take. But my considered opinion, after long reflection, is that whilst in many places the effect of Ulysses on the reader undoubtedly is somewhat emetic, nowhere does it tend to be an aphrodisiac. Ulysses may, therefore, be admitted into the United States.

As the court explained, “If one does not wish to associate with such folks as Joyce describes, that is one’s own choice.”

Legend has it that Random House began typesetting Ulysses within ten minutes of hearing the judge’s ruling. A copy of Judge Woosley’s opinion appeared in every copy of Ulysses sold. Ernst wrote the introduction.

The case was appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, where the case was heard by Chief Judge Martin Manton (not pictured), Judge Learned Hand (pictured left), and his cousin, Judge Augustus Noble Hand (pictured center).

During oral argument, Ernst argued:

There are two questions pertinent to the resolution of this case. The first is: Has the book been accepted and dealt with openly or has it been dealt with under the counter? The answer is that it has been dealt with openly. The other question is that of the intention of the author. As to that, I do not think there can be any serious derogatory comment. The book was written to present a study of the human mind and emotions in certain phrases and it has not been hawked about in a coarse, grasping sense. Those shouting loudest for censorship are the big business fellows who tell dirty stories in Pullman cars. If you blush, it minimizes the corruption and act as a repellant

Hand asked, “You can imagine writings that are rude without being lustful; they would merely be disgusting. Is that your point?”

Ernst responded, “That’s right, your honor. If reasonable men differ on Ulysses, then according to the precedences of our law, the decision of Judge Woosley must stand.”

The lower court decision was affirmed 2-1, with Chief Judge Manton in the dissenting minority. Judge Augustus Hand, writing for the majority, noted, “We think that Ulysses is a book of originality and sincerity of treatment, and that it has not the effect of promoting lust.”

The Second Circuit also held that the harm of an “obscene” book must be judged not from reading select passages but as a result of the whole book. Therefore, if the book as a whole had artistic merit and the allegedly obscene parts were germane to the purpose of the book, then the book could not be viewed as obscene. Judge Augustus Hand wrote:

We believe that the proper test of whether a given book is obscene is its dominant effect. (I.e., is promotion of lust the dominant effect of reading the whole book?) In applying this test, relevancy of the objectionable parts to the theme, the established reputation of the work in the estimation of approved critics, if the book is modern, and the verdict of the past, if it is ancient, are persuasive pieces of evidence; for works of art are not likely to sustain a high position with no better warrant for their existence than their obscene content.

Judge Hand concluded the majority opinion with a historical perspective of the harms of overzealous censorship:

Art certainly cannot advance under compulsion to traditional forms, and nothing in such a field is more stifling to progress than limitation of the right to experiment with a new technique. The foolish judgments of Lord Eldon about one hundred years ago, proscribing the works of Byron and Southey, and the finding by the jury under a charge by Lord Denman that the publication of Shelley’s Queen Mab was an indictable offense are a warning to all who have to determine the limits of the field within which authors may exercise themselves. We think that Ulysses is a book of originality and sincerity of treatment and that it has not the effect of promoting lust. Accordingly it does not fall within the statute, even though it justly may offend many.

The dissent was based on Chief Judge Manton’s view that certain passages undoubtedy were obscene, as evidenced by the fact that they could not even be quoted in the opinion. As the book was a work of fiction “written for the alleged amusement of the reader only,” those passages should be viewed in isolation. Moreover, Chief Judge Manton argued that the book should be examined based on its effect on the entire community, including children. To do otherwise “would show an utter disregard for the standards of decency of the community as a whole and an utter disregard for the effect of the a book upon the average less sophisticated members of society, not to mention the adolescent.” Chief Judge Manton concluded by arguing that masterpieces are not the product of “men given to obscenity or lustful thoughts — men who have no Master” but should serve “a moral standard,” be “noble and lasting,” and “cheer, console, purify, or enoble the life of people.”

The dissent was based on Chief Judge Manton’s view that certain passages undoubtedy were obscene, as evidenced by the fact that they could not even be quoted in the opinion. As the book was a work of fiction “written for the alleged amusement of the reader only,” those passages should be viewed in isolation. Moreover, Chief Judge Manton argued that the book should be examined based on its effect on the entire community, including children. To do otherwise “would show an utter disregard for the standards of decency of the community as a whole and an utter disregard for the effect of the a book upon the average less sophisticated members of society, not to mention the adolescent.” Chief Judge Manton concluded by arguing that masterpieces are not the product of “men given to obscenity or lustful thoughts — men who have no Master” but should serve “a moral standard,” be “noble and lasting,” and “cheer, console, purify, or enoble the life of people.”

The government chose not to appeal to the Supreme Court, ending a decade-long struggle with the United States government and local censorship groups. Further, key components of today’s three-prong Miller obscenity test stem from the District Court decision in United States v. One Book Called “Ulysses,” including the view that the work investigated for obscenity must be considered in its entirety and not merely judged on its parts.

I should note that, 23 years later, the Supreme Court would follow the Second Circuit and rejected the vulnerable-child standard in Roth v. United States and created a test for obscenity that looked at whether a work’s dominant appeal is to the “prurient interest” of average adults, and whether it was “utterly without redeeming social importance.”

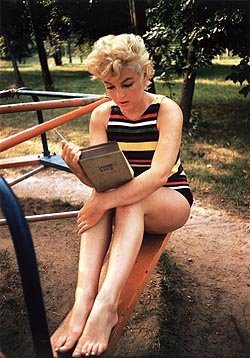

But, that is the subject of another column. The important thing to take away is that Ulysses could be sold in the United States, and Ulysses is still in print today.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net