Before 1952, movies were not provided and protection from censorship under the Constitution. Things changed in 1952 thanks to Roberto Rossellini, Federico Fellini, and an amorous interlude between a wanderer named Saint Joseph and a disturbed peasant who believes herself to be the Virgin Mary.

Before 1952, movies were not provided and protection from censorship under the Constitution. Things changed in 1952 thanks to Roberto Rossellini, Federico Fellini, and an amorous interlude between a wanderer named Saint Joseph and a disturbed peasant who believes herself to be the Virgin Mary.

In the landmark case of Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, the Supreme Court held that film was an artistic medium and should be given the same First Amendment rights as any other form of creative expression. As such, the Court determined that free speech protection equally applied to motion pictures. With its ruling in the Burstyn case, which is often referred to as The Miracle Decision, the Supreme Court reversed earlier rulings and ended decades of censorship in American cinemas.

Prior to the Miracle Decision, it was settled law in America that movies were not entitled to any substantive Constitutional protection  from state censorship. In fact, in an earlier 1915 decision called Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, the U.S. Supreme Court examined whether motion pictures (specifically news reels) were part of “the press of th[is] country” and were therefore afforded protection under the First Amendment as freedom of speech and press. The Court determined that motion pictures were not protected speech. Instead, films were, as a medium, mere commercial entertainment. Worse than that, the Court concluded that movies had the capacity to incite audiences to immoral behavior. As a result, the state and local governments could lawfully restrict, censor, and ban films deemed to be immoral, sacrilegious, or otherwise objectionable. By 1952, seven states and nearly 100 municipalities had laws that established motion picture censor boards. The Supreme Court’s ruling in the Mutual Film case gave these censor boards an unfettered mandate to edit, cut, and even ban objectionable films.

from state censorship. In fact, in an earlier 1915 decision called Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, the U.S. Supreme Court examined whether motion pictures (specifically news reels) were part of “the press of th[is] country” and were therefore afforded protection under the First Amendment as freedom of speech and press. The Court determined that motion pictures were not protected speech. Instead, films were, as a medium, mere commercial entertainment. Worse than that, the Court concluded that movies had the capacity to incite audiences to immoral behavior. As a result, the state and local governments could lawfully restrict, censor, and ban films deemed to be immoral, sacrilegious, or otherwise objectionable. By 1952, seven states and nearly 100 municipalities had laws that established motion picture censor boards. The Supreme Court’s ruling in the Mutual Film case gave these censor boards an unfettered mandate to edit, cut, and even ban objectionable films.

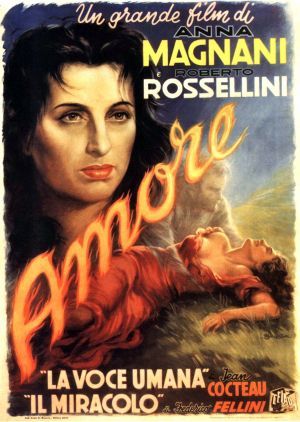

L’Amore was an anthology film that was released in Europe in 1948. The film consisted of two short segments. The first, “La voce umana,” was based on Jean Cocteau’s play The Human Voice. However, it was the film’s other segment, “Il Miracolo” (or “The Miracle”) that sparked a controversy. The plot of “The Miracle,” written by Roberto Rossellini, involves a young shepherdess (played by Anna Magnani) who meets a wandering vagabond (played by Federico Fellini, who also directed). She is convinced that he is Saint Joseph and begs him to take her away to paradise. In response, he gives her a drink and she falls asleep. The next day, Saint Joseph has abandoned her, and she finds that she is pregnant. The townspeople mock her and drive her from the town. The story ends with the shepherdess giving birth to what she believes to be the son of God.

As expected, “The Miracle” was not well received by conservative groups, which claimed the film was vile, harmful, and blasphemous. The film was protested in Paris by picketers.

In 1950, L’Amore was first shown in New York (with English subtitles). The film, which was combined with two other short subjects — Jean Renoir’s A Day in the  Country and Marcel Pagnol’s Jofroi — and released under the title Ways of Love. Despite being voted the best foreign language film of 1950 by the New York Film Critics Circle, the film once again sparked controversy. Francis Cardinal Spellman, archbishop of New York, ordered that his denouncement of “The Miracle” and Rossellini be read at every Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and he pronounced that all American Catholics should boycott the film and write the New York State Board of Regents to ask them to rescind the films license.

Country and Marcel Pagnol’s Jofroi — and released under the title Ways of Love. Despite being voted the best foreign language film of 1950 by the New York Film Critics Circle, the film once again sparked controversy. Francis Cardinal Spellman, archbishop of New York, ordered that his denouncement of “The Miracle” and Rossellini be read at every Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and he pronounced that all American Catholics should boycott the film and write the New York State Board of Regents to ask them to rescind the films license.

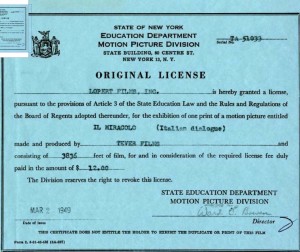

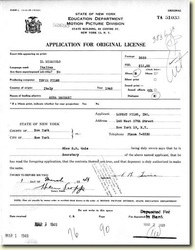

At the time when”The Miracle” was released, N. Y. Education Law, §122 required that a film be licensed before it could be shown in theaters. This license could be revoked if the New York State Board of Regents found that a film was sacrilegious. The law provided:

The director of the [motion picture] division [of the education department] or, when authorized by the regents, the officers of a local office or bureau shall cause to be promptly examined every motion picture film submitted to them as herein required, and unless such film or a part thereof is obscene, indecent, immoral, inhuman, sacrilegious, or is of such a character that its exhibition would tend to corrupt morals or incite to crime, shall issue a license therefor. If such director or, when so authorized, such officer shall not license any film submitted, he shall furnish to the applicant therefor a written report of the reasons for his refusal and a description of each rejected part of a film not rejected in toto.

The New York Education Department had issued a license to allow showing of “The Miracle,” but the Education Department’s governing body, the New York Regents (chaired by Wilson) reexamined “The Miracle” after allegedly receiving hundreds of letters, telegrams, postcards, affidavits, and other communications that consisted of both condemnation and praise for protesting the showing of the film. The Regents concluded that “The Miracle” was sacrilegious religious bigotry. On February 16, 1951, after notice and a hearing, the Commissioner of Education was ordered to rescind the picture’s license.

With the assistance of the American Civil Liberties Union, the film’s distributor, Joseph Burstyn, Inc., brought suit in New York state court to challenge the Regents’ ruling on the grounds that the statute violated the First Amendment as a prior restraint upon freedom of speech and of the press, “that it is invalid under the same Amendment as a violation of the guaranty of separate church and state and as a prohibition of the free exercise of religion,” and “that the term ‘sacrilegious’ is so vague and indefinite as to offend due process.” The Regents’ decision was upheld by the New York court as well as the Court of Appeal. Burstyn then appealed the decision to the Supreme Court, who agreed to hear the case.

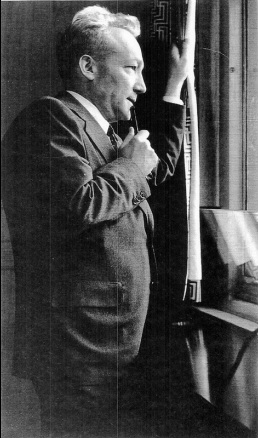

At oral argument, held on April 24, 1952, Ephraim London, Burstyn’s attorney (pictured left), argued for the power of film. He stated, “I do not think,” he told the justices, “one can name a great novel, play or essay that does not both entertain and communicate ideas simultaneously. . . . The mere fact that a communication is effective does not mean it should be denied freedom guaranteed by the Constitution.” In response, New York Solicitor General Charles A Brind Jr. argued that the New York statute prohibited films that were “obscene, indecent, immoral, or sacrilegious,” which meant that no film should be allowed to vilify the religious beliefs of any segment of the population. In response to questions from Chief Justice Fred Vinson, Brind admitted that movies did have First Amendment protection. However, the Solicitor countered that this didn’t mean that all licensing requirements are unconstitutional.

At oral argument, held on April 24, 1952, Ephraim London, Burstyn’s attorney (pictured left), argued for the power of film. He stated, “I do not think,” he told the justices, “one can name a great novel, play or essay that does not both entertain and communicate ideas simultaneously. . . . The mere fact that a communication is effective does not mean it should be denied freedom guaranteed by the Constitution.” In response, New York Solicitor General Charles A Brind Jr. argued that the New York statute prohibited films that were “obscene, indecent, immoral, or sacrilegious,” which meant that no film should be allowed to vilify the religious beliefs of any segment of the population. In response to questions from Chief Justice Fred Vinson, Brind admitted that movies did have First Amendment protection. However, the Solicitor countered that this didn’t mean that all licensing requirements are unconstitutional.

One month later, on May 26, 1952, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously reversed the state appeals court decision and lifted the ban on “The Miracle.” Justice Clark wrote the final decision and essentially reversed the Court’s earlier holding in Mutual Film. The Court held that the fact that motion pictures are produced by a large, profitable industry does not remove the protection of Constitutional guarantees. Films were given protection under the First and Fourteenth Amendments, and movies which offended a particular religious group cannot, for that reason alone, be banned. They recognized the Miracle Case as ‘‘the first to present squarely . . . the question whether motion pictures are within the ambit of protection which the First Amendment, through the Fourteenth, secures to any form of ‘speech’ or ‘the press.’’’ The Court held ‘‘that motion pictures are a significant medium for the communication of ideas’’ and recognized that the movies ‘‘may affect public attitudes and behavior in a variety of ways, ranging from direct espousal of a political or social doctrine to the subtle shaping of thought which characterizes all artistic expression.’’ Movies’ significance ‘‘as an organ of public opinion,’’ the Court stated, ‘‘is not lessened by the fact that they are designed to entertain as well as to inform.’’ Nor would the Court dilute constitutional protection for motion pictures on the ground that they ‘‘are published and sold for profit.’’ Like ‘books, newspapers, and magazines, motion pictures won recognition as ‘‘a form of expression whose liberty is safeguarded by the First Amendment.’’ The Court thereupon included ‘‘expression by means of motion pictures . . . within the free speech and free press guaranty of the First and Fourteenth Amendments’’ and overruled the holdings in Mutual Film.

To summarize, The Miracle Decision has three basic holdings:

1) Motion pictures are included within the free speech and press guarantees of the First Amendment;

2) The New York Education Law prohibiting the exhibition of any film without a license was void as a prior restraint on protected expression; and

3) A movie cannot be banned on the charge of sacrilege.

It should be noted that the Court also said in dicta (nonbinding language) that a clearly drawn obscenity statute to regulate motion pictures might be upheld. (Remember, the Regents only found the film to be a sacrilege and not obscene.) During oral argument, Ephraim London, Burstyn’s attorney, argued that “a movie cannot ever be censored in advance.” This caused a reaction from Justice Sherman Minton, who asked, “Not even for obscenity?” London replied: “That’s right.” Ephram’s position was explicitly rejected by the Court’s dicta.

After the decision, Bosley Crowther, a New York Times film critic who had been cited several times in the opinion, wrote:

After the decision, Bosley Crowther, a New York Times film critic who had been cited several times in the opinion, wrote:

“It is significant that the Miracle case was fought by an independent importer of foreign pictures, Joseph Burstyn, without the support of the organized film industry, and that its outcome reasserts the freedom of thought and expression which other elements in the industry seem ready to resign in the face of dubious pressures and dark depressing fears. The Supreme Court has reminded the filmmakers that they live in a society of free men.”

Burstyn died the year after his Supreme Court victory. Again, film critic Bosley Crowther, summed up his contributions:

“Though Mr. Burstyn is no longer here to see it done, the case he singly and bravely carried.may yet spearhead full freedom for the screen.”

Before the Miracle decision, the movie industry was viewed just another business, fully subject to government regulation. The decision changed American film forever by affording Constitutional protection to films. The Miracle Decision was a turning point for the film industry and free speech movements in the United States. It also reinforced the idea that even popular entertainment (which naturally includes comic books) is Constitutionally protected speech.

For a complete collection of material related to the decision, please go to http://iarchives.nysed.gov/PubImageWeb/listCollections.jsp?id=67922

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net