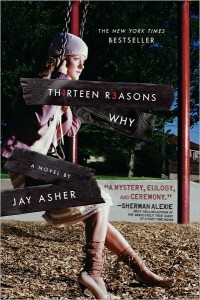

By virtue of dealing with the upsetting subject of teen suicide, it’s no surprise that 13 Reasons Why, both the hit Netflix show and the frequently challenged YA novel, are regularly mired in controversy. But as a recent A.V. Club article by Alex McLevy points out, a new study that some people are saying offers clear-cut proof that the show is, in fact, leading to teen suicide attempts, should be taken with a large grain of salt, if for no other reason than when dealing with something as complicated as suicide, there is no such thing as a straight answer.

By virtue of dealing with the upsetting subject of teen suicide, it’s no surprise that 13 Reasons Why, both the hit Netflix show and the frequently challenged YA novel, are regularly mired in controversy. But as a recent A.V. Club article by Alex McLevy points out, a new study that some people are saying offers clear-cut proof that the show is, in fact, leading to teen suicide attempts, should be taken with a large grain of salt, if for no other reason than when dealing with something as complicated as suicide, there is no such thing as a straight answer.

From the McLevy article,

The troubling reality of the phenomenon, and the fears it inspires, have been a mainstay of cultural concern for decades. Which is why a new study linking the popular Netflix series 13 Reasons Why with an increase in teen suicide attempts should be viewed with a massive dose of skepticism about any conclusions to be drawn from it. This is merely the latest scapegoat for a problem that rightfully generates a lot of hand-wringing about how to combat it—and a lot of wrong-headed impulses about controlling art. (Even in the case of cheap sensationalism like 13 Reasons Why, whose depiction of teen suicide is far from subtle.)

The study conducted by the University of Michigan consisted of questionnaires of presented to 87 children and teens with suicidal concerns in a psychiatric emergency room. A questionnaire was also given to parents and guardians, but that was more focused on whether the adults had any awareness of the show. According to the abstract for the study, 13 Reasons Why: Viewing Patterns and Perceived Impact Among Youths at Risk for Suicide, half of the youths who participated in the study had seen at least one episode of the show, and of that half, just over half “(51%) believed the series increased their suicide risk to a nonzero degree”, which means that on a scale of one to ten, it could have been a one they selected for the internal increase they felt. The abstract also mentions that “Youths with more depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation were more likely to identify with the lead characters and report negative affect while viewing.”

If this study had been done in 1986, it’s likely that the same results could have been found for The Smiths song There Is a Light That Never Goes Out. The A.V. Club article by Alex McLevy also points out that since the beginning of time, depressed kids seek out depressing music, books, movies, etc. But so do non-depressed kids. The reason most of the kids in the psychiatric emergency ward had seen the show, is because the first season was the second highest viewed Netflix original within the first 30 days after its premiere. And 13 Reasons Why demonstrated an 18% growth from episode one to episode two, which is extremely unusual on a site designed towards binge-watching, but according to Variety and Jumpstart, that’s because the controversial show exceeded expectations with word of mouth recommendations. With that kind of popularity, it should not be surprising that half of any group of teenagers have seen at least one episode.

Victor Hong, medical director of psychiatric emergency service at Michigan Medicine, said in response to the findings, “Our study doesn’t confirm that the show is increasing suicide risk. But it confirms that we should definitely be concerned about its impact on impressionable and vulnerable youth. Few believe this type of media exposure will take kids who are not depressed and make them suicidal. The concern is about how this may negatively impact youth who are already teetering on the edge.”

But that still puts the responsibility on the show, and art is not responsible for the mental health of our youth. McLevy brings up the well known Werther Effect, which is the fancy name for copycat suicides, named for the protagonist in Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther which inspired young men to kill themselves in real life, sometimes even dressing up as the character or leaving the book open to relevant passages in lieu of a suicide note. That was 200 hundred years ago, that is how well worn these arguments and concerns are.

And the Netflix show has added warnings before the episodes. It has included information after the episodes, imploring people in who need help or who know people who need help to go to 13reasonswhy.info to find crisis resources. They’ve shot a series of videos about depression, drug and alcohol abuse, understanding consent, talking with your teen about the show, and more – all to try and help open up a dialogue between teens and parents. They’ve more than met their responsibility for handling a difficult subject matter responsibly. Now it’s time we take the opening they’ve provided, and start having those difficult conversations with teens we care about.

It is easy to understand why people look for easy answers to the complex questions surrounding teen suicide. It is a terrifying reality for a community that almost universally agrees it is the worst possible outcome for the limitless potential of a life. But a Netflix show is no more responsible than Goethe was in his day. People who want to kill themselves will gravitate toward things that confirm their own beliefs. As a society, we need to take the opportunities presented by art to have open dialogues about these things, and not hope that if we just remove every reference to it, it will miraculously go away.

As McLevy writes in his article,

But it’s important to keep the focus where it belongs, which is on the troubling reality that art like 13 Reasons Why only highlights and calls attention to: Namely, life sucks for a lot of kids, and the fact that some of them entertain suicidal thoughts is a societal problem, not a problem of access to an online streaming service.