In early 2015, the critically acclaimed comic collection Palomar by Gilbert Hernandez was called “child porn” by the mother of a high school student in Rio Rancho, New Mexico. Initially, unbiased details are difficult to come by because of biased reporting from a local news station, which labeled the book “sexual, graphic, and not suitable for children.”

In early 2015, the critically acclaimed comic collection Palomar by Gilbert Hernandez was called “child porn” by the mother of a high school student in Rio Rancho, New Mexico. Initially, unbiased details are difficult to come by because of biased reporting from a local news station, which labeled the book “sexual, graphic, and not suitable for children.”

When Catrenna Lopez found objectionable material in Palomar after her 14-year-old son checked it out of the Rio Rancho High School library, she didn’t simply file a challenge with the school — she took her objections to the local media. A quick Google search would have turned up the accolades for the book and its literary value, but local news outlet KOAT didn’t comes close to a fair an accurate report, declaring that “we can’t show you any of the images because they’re too sexual and very graphic” and quoting Lopez’s claims that she found “child pornography pictures and child abuse pictures.” Of further concern were indications in the KOAT report that unnamed individuals in the school administration support Lopez’s claims that the book is “clearly inappropriate.”

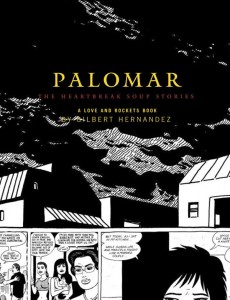

Needless to say, Palomar is not actually a collection of child porn — Publishers Weekly called it “a superb introduction to the work of an extraordinary, eccentric and very literary cartoonist” and it often draws comparisons to the magic realism of novelists such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez. The book collects Hernandez’s “Heartbreak Soup” stories, which originally appeared in the Love and Rockets series, a collaboration with his brothers Jaime and Mario. Gilbert Hernandez’s stories focus on the interconnected lives of characters from one family in the fictional South American town of Palomar.

CBLDF took immediate action to help defend the book, taking the lead with frequent partners Kids’ Right to Read Project in sending a letter to Superintendent V. Sue Cleveland to protest the allegations against Palomar. The letter argued that one parent’s objections cannot be allowed to determine the rights of other students to enjoy Palomar or any other literary work. And the letter urged the school district to adhere to its own guidelines, which state that reviews to challenged materials be treated “objectively, unemotionally, and as a routine matter.” The Rio Rancho review committee agreed. By a 5-3 vote, the committee voted to retain the book. Although Palomar is slated to return to shelves before the 2015-2016 school year, however, someone within the district has imposed a requirement for students under 18 to have parental permission to access it.

Additionally, emails released via FOIA request to local radio station KUNM show that RRPS initially did not follow the challenge policy, and the book’s record was in fact deleted from the computerized library catalog in response to the first verbal complaint from Lopez. It was only after the district received national scrutiny regarding the book challenge that an administrator informed employees the policy would be followed and a review committee assembled. Even after that committee recommended that the book be restored to shelves, an email exchange between the school’s principal and vice principal showed that both harbored some hope that the superintendent would still overturn that decision.