There are a few things in life that everyone should know: Look both ways before crossing the street. Always eat your vegetables. If you have nothing nice to say, don’t say anything at all. But, most important of this sage wisdom, is that you should never ever tug on Superman’s cape. In the 1950s, Fredrick Wertham did just that as part of his attack on the comic industry. However, unlike the many other combatants that fell victim to Wertham’s attacks, the Man of Steel not only continued to thrive under the scrutiny, but his creators attacked back. As a result, Wertham was humiliated and forced to join the likes of Lex Luthor, Metallo, and Brainiac on the list of many opponents who have been defeated by the greatest and most beloved hero of all time.

There are a few things in life that everyone should know: Look both ways before crossing the street. Always eat your vegetables. If you have nothing nice to say, don’t say anything at all. But, most important of this sage wisdom, is that you should never ever tug on Superman’s cape. In the 1950s, Fredrick Wertham did just that as part of his attack on the comic industry. However, unlike the many other combatants that fell victim to Wertham’s attacks, the Man of Steel not only continued to thrive under the scrutiny, but his creators attacked back. As a result, Wertham was humiliated and forced to join the likes of Lex Luthor, Metallo, and Brainiac on the list of many opponents who have been defeated by the greatest and most beloved hero of all time.

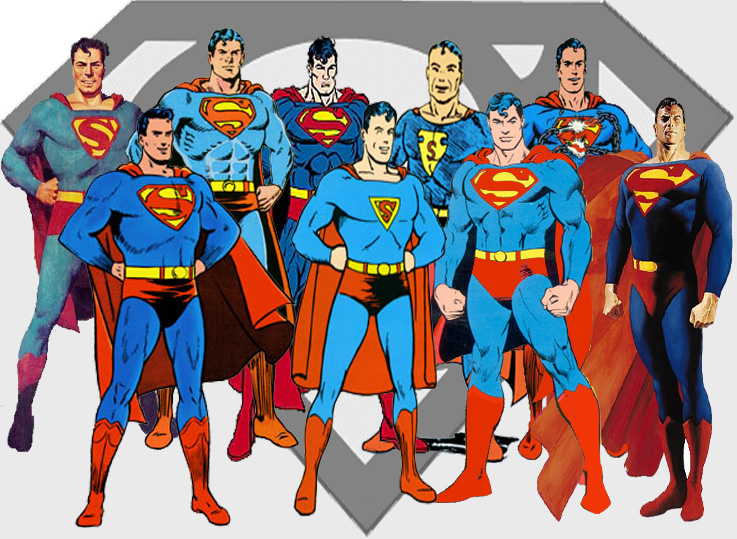

I will start this article by saying that I could never be impartial when it comes to Superman. Superman is the greatest comic book character ever created. He is the prototype from which all other superheroes follow. Superman has thrived in his never-ending battle for almost 75 years and is as popular now as when he first appeared in Action Comics #1.

I will start this article by saying that I could never be impartial when it comes to Superman. Superman is the greatest comic book character ever created. He is the prototype from which all other superheroes follow. Superman has thrived in his never-ending battle for almost 75 years and is as popular now as when he first appeared in Action Comics #1.

With apologies to Howard Stern, Superman is truly the king of all media, having conquered music, comics, magazines, newspapers, books, radio, film, television, and even the internet. A Gallup Poll concluded that the public knew more about Superman than about American history. The S shield symbol, one of the most recognizable in the world, is synonymous with everything that is good and decent. In fact, during the 90s, when comics became grim and gritty, Superman still stood for morals and ideals. He was the light in that dark time. On a personal level, Superman’s unwavering dedication to truth and justice had a huge influence on me when I was growing up and still inspires me to this day. My first published work was an historical analysis of Superman’s publication history. My first novel has been called “a love letter to the Man of Steel’s mythology and heroic archetype” and is dedicated, in part, to Siegel and Shuster, his creators. It’s a life-long dream to someday write his adventures. I say all of this so that when it comes to a fight between my hero and Fredric Wertham, the man who help stunt the creative growth of the comic book industry for decades, I wanted you to be clear on whose corner I am in.

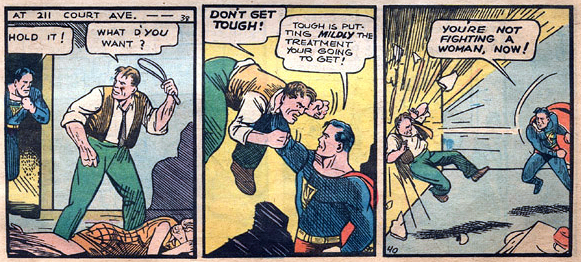

When Superman first appeared in 1938, he was an anti-establishment social crusader who fought for the common people against the interests of the rich and powerful. His early adventures had the Man of Steel facing off against wife beaters, a corrupt judicial system, lynch mobs, and even corporate robber barons. Mark Waid, in Superman in the Fifties, described this early Superman as a “diamond in the rough: a quick-tempered social activist whose dedication to the ideals of truth and justice apparently put him above the rules and regulations of society.”

But, by the 1950s, the Last Son of Krypton had mellowed. Instead of fighting for the oppressed against the government, he embraced the establishment and became its most staunch patriotic supporter and advocate. This change came about through the combination of his radio and film appearances as well as the fact that he was licensed out as the spokesperson for everything from gasoline to cereal. Earlier, in 1940, new editor Whitney Ellsworth instituted a moral code. As Les Daniels explains in his book Superman, the Complete History (page 41):

Among Ellsworth’s most important tasks was determining a proper code of conduct for Superman. In the first newspaper adventure, Superman had deliberately torn the wings off a plane full of bad guys…. Such melodramatics worried Harry Donnenfeld: Superman was becoming a valuable property, one that appealed to a younger audience, and the publisher was anxious to avoid any repetition of the censorship problems associated with his early pulp magazines (such as the lurid Spicy Detective). It was up to Ellsworth to impose tight editorial controls on Jerry Siegel. Henceforth, Superman would be forbidden to use his powers to kill anyone, even a villain.

A copy of DC’s editorial standards (in the form of a memo by Ellsworth) was submitted to Congress as part of the testimony of Gunnar Dybwad, executive director of the Child Study Association of America, during the 1954 Hearing on Juvenile Delinquency. The memo reads:

EXHIBIT No. 21

NATIONAL COMICS PUBLICATIONS INC.

EDITORIAL POLICY FOR SUPERMAN D─C PUBLICATIONS

1. Sex. ─ The inclusion of females in stories is specifically discouraged. Women, when used in plot structure, should be secondary in importance, and should be drawn realistically, without exaggeration of feminine physical qualities.

2. Language. ─ Expessions [sic] having reference to the Deity are forbidden. Heroes and other “good” persons must use basically good English, through some slang and other colloquialism may be judiciously employed. Poor grammar is used only by crooks and villains ─ and not always by them.

3. Bloodshed. ─ Characters ─ even villains ─ should never be shown bleeding. No character should be shown being stabbed or shot or otherwise assaulted so that the sanguinary result is visible. Acts of mayhem are specifically forbidden. The picturization of dead bodies is forbidden.

4. Torture. ─ The use of chains, whips, or other such devices is forbidden. Anything having a sexual or sadistic implication is forbidden.

5. Kidnaping [sic] . ─ The kidnaping [sic] of children is specifically forbidden. The kidnaping [sic] of women is discouraged, and must never have any sexual implication.

6. Killing. ─ Heroes should never kill a villain, regardless of the depth of the villainy. The villain, If he is to die, should do so as the result of his own evil machinations. A specific exception may be made in the case of duly constituted officers of the law. The use of lethal weapons by women ─ even villainous women ─ is discouraged.

7. Crime. ─ Crime should be depicted in all cases as sordid and unpleasant. Crime and criminals must never be glamorized. All stories must be written and depicted from the angle of the law ─ never the reverse. Justice must triumph in every case.

In general, the policy of Superman D─C Publications is to provide interesting, dramatic, and reasonably exciting entertainment without having recourse to such artificial devices as the use of exaggerated physical manifestations of sex, sexual situations, or situations in which violence is emphasized sadistically. Good people should be good, and bad people bad, without middle ground shading. Good people need not be “stuffy” to be good, but bad people should not be excused. Heroes should act within the law, and for the law.

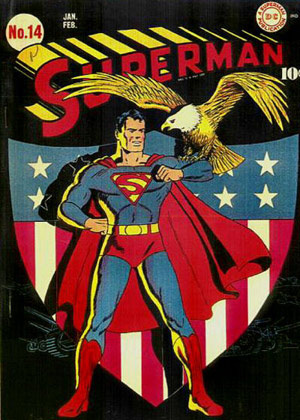

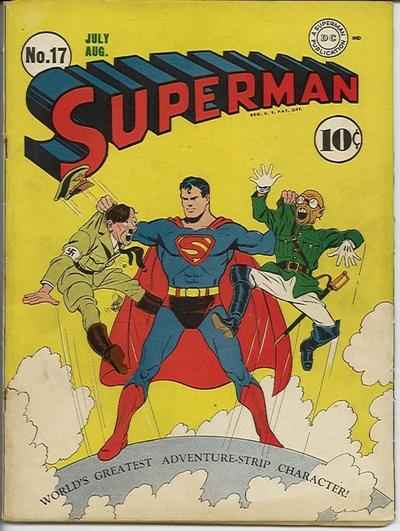

Superman was becoming an American ideal. Superman fought the Axis enemies on the covers of his comics long before America entered World War II. Inside the book, and throughout WWII, Superman supported war bonds, recycling, and other stateside activities to support the troops, all while stopping numerous terrorist attacks on American soil. An impassioned plea from Superman (as performed by Bud Collier on the radio program) inspired over 250,000 listeners to mail in pledges to buy war stamps. In fact, the original opening of the radio program, which described Superman’s fight as “a never-ending battle for truth and justice,” was changed during Word War II to “Truth, Justice and the American way.” In the real world, soldiers named tugs, jeeps, planes, and tanks after the hero. Because Superman so embodied the American ideal, Josef Goebbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda, denounced Superman in April 1940, In Das Schwarze Korps, the weekly newspaper of the Nazi S.S. Goebbels, and attacked the comic and its Jewish writers:

Superman was becoming an American ideal. Superman fought the Axis enemies on the covers of his comics long before America entered World War II. Inside the book, and throughout WWII, Superman supported war bonds, recycling, and other stateside activities to support the troops, all while stopping numerous terrorist attacks on American soil. An impassioned plea from Superman (as performed by Bud Collier on the radio program) inspired over 250,000 listeners to mail in pledges to buy war stamps. In fact, the original opening of the radio program, which described Superman’s fight as “a never-ending battle for truth and justice,” was changed during Word War II to “Truth, Justice and the American way.” In the real world, soldiers named tugs, jeeps, planes, and tanks after the hero. Because Superman so embodied the American ideal, Josef Goebbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda, denounced Superman in April 1940, In Das Schwarze Korps, the weekly newspaper of the Nazi S.S. Goebbels, and attacked the comic and its Jewish writers:

Jerry Siegel, an intellectually and physically circumcised chap who has his headquarters in New York… The inventive Israelite named this pleasant guy with an overdeveloped body and underdeveloped mind “Superman.

At the same time, the German American Bund sent Joe Shuster hate mail and picketed the offices of DC Comics. In Italy, Mussolini banned Superman comics, along with all other American made comics except those featuring Mickey Mouse (apparently Il Duce was mad about the Mouse, but that is a story for another day).

At the same time, the German American Bund sent Joe Shuster hate mail and picketed the offices of DC Comics. In Italy, Mussolini banned Superman comics, along with all other American made comics except those featuring Mickey Mouse (apparently Il Duce was mad about the Mouse, but that is a story for another day).

While other comics were becoming darker and delving into the macabre world of horror and crime, Superman still served as a beacon of good wholesome fun. The powers that be at DC took steps to associate the character with American ideal products and a team of censors reviewed his books to make sure that Superman maintained his wholesome reputation as “the Big Blue Boy Scout.” Specifically, in 1941, DC formed an editorial board to certify that comic books were being held up to high moral standards. The names of these editorial boards (which consisted of psychiatrists, child welfare experts, and some famous well-respected citizens) were printed on the inside cover of all DC books.

The book, and the character, appeared beyond reproach.

Well, that is, until Fredrick Wertham came along.

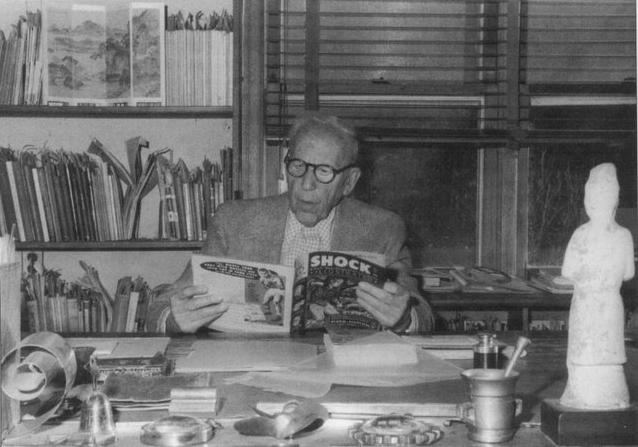

As comics fan are aware, Wertham was a child psychiatrist that published an impassioned attack on crime comic books, Seduction of the Innocent, which blamed comics for the growing problem of juvenile delinquency in America. This book is commonly viewed as the stimulus that stirred the public moral panic and created a backlash against comics and their creators. This, in turn, led to the destruction of a large number of comic publishers and to the imposition of the Comics Code, which stifled creativity for decades. Tom De Haven called Wertham the “industry’s real-life supervillain.”

But, Superman isn’t a crime comic, some would say.

Not according to Wertham, who described Superman and his fellow heroes as:

The Superman type of comic books tends to force and super-force. Dr. Paul A. Witty, professor of education at Northwestern University, has well described these comics when he said that they “present our world in a kind of Fascist setting of violence and hate and destruction. I think it is bad for children,” he goes on, “to get that kind of recurring diet … [they] place too much emphasis on a Fascist society. Therefore the democratic ideals that we should seek are likely to be overlooked.

David Hajdu, author of The Ten Cent Plague, writes:

Unlike many critics of crime, horror, and romance comics in the newspaper columns and state assemblies, Wertham considered superhero comics as dangerous as any others. In fact, he reserved a specially toxic venom for National/DC’s popular trio of heroes, Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman, whom he saw respectively, as exemplars of fascism, homoeroticism, and sadomasochism.

Wertham goes on to argue that Superman caused children to be narcissistic.

Rather than doing good deeds for the sake of morality and character, Wertham wrote that Superman influences children to do a good deed for the sake of fame and potential rewards; Wertham even goes so far as to argue that Superman’s influence is so dangerous that the character encourages children to create accidents and problems in order to be seen solving them.

Indeed, even when he testified in front of the Senate, Wertham took the time to single out Superman, noting that the comic books aroused in children “phantasies [sic] of sadistic joy in seeing other people punished over and over again while you yourself remain immune.” Wertham called it the “Superman complex.”

Perhaps the most incredible claim leveled at the Man of Tomorrow is that Wertham labels him an un-American fascist, he writes:

Actually, Superman (with the big S on his uniform — we should, I suppose, be thankful that it is not an S.S.) needs an endless stream of ever new submen, criminals and “foreign- looking” people not only to justify his existence but even to make it possible. It is this feature that engenders in children either one or the other of two attitudes: either they fantasy themselves as supermen, with the attendant prejudices against the submen, or it makes them submissive and receptive to the blandishments of strong men who will solve all their social problems for them — by force.

Wertham argued that Superman was actually the epitome of Nazism. Superman’s speed, strength, and near invulnerability, Wertham argued, drew close the concept of the perfect man and race that was located at the core of the Nazi Party’s ideology and thus provided subliminal support for the Nazi Party. This theme was adopted by CatholicWorld, who stated that Superman personified an ideal “very much in the style of a Nazi pamphleteer.” Gershom Legman, an American cultural critic and essayist, wrote that Superman “is really peddling a philosophy of ‘hooded justice’ in no way distinguishable from that of Hitler….” Wertham and friends’ condemnation of Superman for being an un-American Nazi mere years after the Nazi party condemns him for being a pro-American Jew is dramatic irony on par with the works of Shakespeare. Of course, it should not have really been a surprise since Wertham is also quoted as saying, “I think Hiter was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry.”

Wertham argued that Superman was actually the epitome of Nazism. Superman’s speed, strength, and near invulnerability, Wertham argued, drew close the concept of the perfect man and race that was located at the core of the Nazi Party’s ideology and thus provided subliminal support for the Nazi Party. This theme was adopted by CatholicWorld, who stated that Superman personified an ideal “very much in the style of a Nazi pamphleteer.” Gershom Legman, an American cultural critic and essayist, wrote that Superman “is really peddling a philosophy of ‘hooded justice’ in no way distinguishable from that of Hitler….” Wertham and friends’ condemnation of Superman for being an un-American Nazi mere years after the Nazi party condemns him for being a pro-American Jew is dramatic irony on par with the works of Shakespeare. Of course, it should not have really been a surprise since Wertham is also quoted as saying, “I think Hiter was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry.”

As a result of these attacks, Wolcott Gibbs, a critic for the New Yorker, warned, “The evidence that Dr. Wertham has gathered is overpowering…. I like to think that Superman and his pals are up against the battle of their perverse, fantastic, and foolish lives.”

So, how did the makers of Superman (collectively known as Superman, Inc at the time) respond to these allegations? The safest thing to do would have been to lay low. This was especially true after EC Publisher MC Gaines was crucified in the media after his appearance in the congressional hearings. Clearly, the deck was stacked against comics. Superman’s best move would have been to hide out in his Fortress of Solitude until the whole comics scare blew over. But, then who would challenge Wertham’s views?

This looked like a job for Superman!

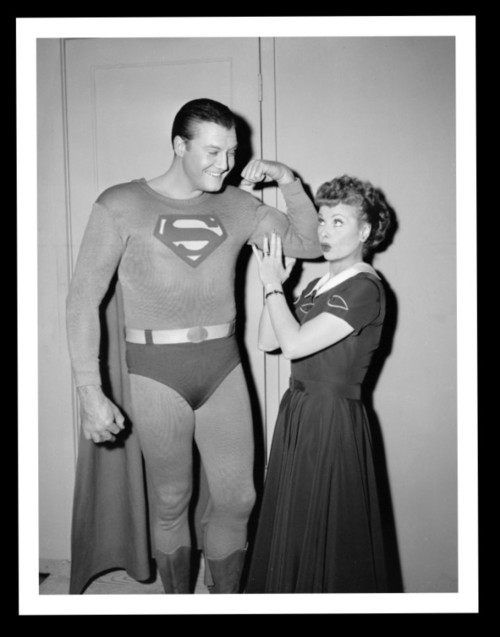

Instead of passively waiting for the tide to turn, Superman forged his way onto a new American frontier: the world of television. In doing so, Superman conquered yet another medium and prevailed in the eyes of the public against Wertham’s smear campaign. Larry Tye in his book, Superman: The High Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero, explains:

This was no time to launch another Superman experiment. Not in 1951, when the whole comic book world was running scared. Not when the medium into which he was being catapulted, television, was so callow and unclear whether it would succeed, and it was perfectly clear that actors with promise would opt for Hollywood or Broadway. Not when Superman himself was being labeled a sociopath.

Tye continues, explaining precisely why Superman pushed through the challenges and into television:

But that wasn’t the way National Comics or Robert Maxwell thought. They knew that there more children than ever in America, where soldiers had come home from Europe and made up for lost time by igniting an unprecedented boom in babies. They also knew that radio was dying as a venue for children’s adventure and that movie serials wouldn’t be far behind. While TV might be new and untested, so where comic books when Superman broke through in that medium. Now was precisely the time when the battered Superman of the static page could use a lift onto the small screens that were turning up in America’s dens and playrooms. For Superman’s owners, the question wasn’t whether, but when to push ahead . . . .

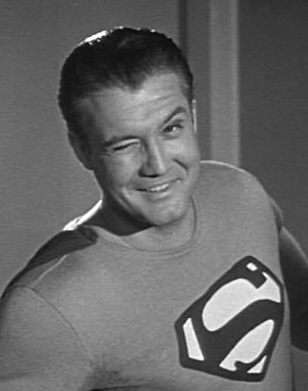

And push ahead they did. The Adventures of Superman debuted in 1953, with George Reeves playing the Man of Steel (and Ellsworth as producer). Almost immediately, the show became tremendously popular and is considered a television classic. Superman even reached the pinnacle of his day: a guest spot on the 1950s most popular situation comedy, I Love Lucy. Les Daniels explains, “such guest shots were generally reserved for Hollywood icons like John Wayne, Rock Hudson, or Harpo Marx, but in 1956, Reeves joined their illustrious company — or rather Superman did.” (I should add that Reeves was uncredited for the role).

And push ahead they did. The Adventures of Superman debuted in 1953, with George Reeves playing the Man of Steel (and Ellsworth as producer). Almost immediately, the show became tremendously popular and is considered a television classic. Superman even reached the pinnacle of his day: a guest spot on the 1950s most popular situation comedy, I Love Lucy. Les Daniels explains, “such guest shots were generally reserved for Hollywood icons like John Wayne, Rock Hudson, or Harpo Marx, but in 1956, Reeves joined their illustrious company — or rather Superman did.” (I should add that Reeves was uncredited for the role).

The show preached a messages of tolerance and good will. The television show continued to showcase the same all ages positive messages that ran through the comic throughout its 104 episode run. In a 1954 interview, George Reeves explained:

In Superman, we’re all concerned with giving kids the right kind of show. We don’t go too much for violence. Once, for a big fight scene, we had several of the top wrestlers in town do the big brawl. It was considered too rough by the sponsors and producer, so it was toned down. Our writers and the sponsors have children, and they are all very careful about doing things on the show that will have no adverse effect on the young audience. We even try in our scripts, to give a gentle message of tolerance and stress that a man’s color and race and religious beliefs should be respected.

This apparently did not faze Wertham, who wrote:

Some movie writers look in crime comic books for new tricks. For instance the producer of the movie serial Atom Man vs Superman, which was shown in about half the movie theaters of the country, is said to be “an avid reader of the comics, from which he gets many of his ideas.”

Television has taken the worst out of comic books, from sadism to Superman. The comic-book Superman has long been recognized as a symbol of violent race superiority. The television Superman, looking like a mixture of an operatic tenor without his armor and an amateur athlete out of a health-magazine advertisement, does not only have “superhuman powers,” but explicitly belongs to a “super-race.”

But the fight did not end there. In addition to putting their character in the spotlight in other media, DC Comics took the fight to Wertham. Larry Tye, in Superman: The High Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero, explains:

Mort [Weisenger] took on Fredric Wertham. In a radio debate, Wertham talked about how all of the two hundred inmates he had interviewed at reform school had read Superman, prompting Weisenger to ask, “Did you get them to confess that they also chew bubble gum, play baseball, eat hot dogs, and go to the movies?” There was no joking in an “investigation” he did for Better Homes and Gardens in 1955 entitled “How They’re Cleaning Up the Comic Books” — and no mention, as he outlined the “stern self-censorship” publishers were pursuing to purge comics of everything from sex to cannibalism and bad grammar, that Weisenger was not a disinterested investigator but a top editor at America’s biggest comic book publisher.

The March 1955 issue of Better Homes and Gardens referred to by Tye had a lengthy article that explained the need for the Comics Code and how it functioned. It started out with a description of every comic book ever made “from Action Comics to Ziggy Pig.” (Ziggy Pig appeared in a back-up in the 1940’s Timely Krazy Komics in a short-lived five issue run from 1944-1946.)

The March 1955 issue of Better Homes and Gardens referred to by Tye had a lengthy article that explained the need for the Comics Code and how it functioned. It started out with a description of every comic book ever made “from Action Comics to Ziggy Pig.” (Ziggy Pig appeared in a back-up in the 1940’s Timely Krazy Komics in a short-lived five issue run from 1944-1946.)

Weisenger wrote:

…some anxious parents concerned with the reading habits of their children will note something new has been added to the familiar [comic book]…. This seal is another and the latest answer to the comic-book industry’s bitterest critics. During the next 30 days, as millions of comic books introducing this seal flood the magazine racks of Candy stores, supermarkets, and pharmacies throughout the country, the public will be informed that the seal is the symbol of the industry’s new policy of stern self-censorship… Comic-book houses are on the hot seal today as a result of conscienceless editing by a minority of unethical publishers within their ranks… it is because of the past activities of the lunatic fringe that the entire industry has been smeared….

I should note that the article also stated that, according to Judge Murphy, the Comics Code hired all women with college backgrounds “because it has been my experience that women are more sensitive than men in most matters of good taste.” Les Daniels, in DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World’s Favorite Comic Book Heroes adds:

DC was one of the few comic book publishers to survive [The Comics Code Crunch]. “We didn’t have titles that were really attackable,” says Irwin Donnenfeld. “And I went around the country. I spoke before PTA groups. I was on TV discussing the problems of comics and how helpful they are in teaching kids to read.”

In my research, I discovered that Wertham struck back one last time on April 9, 1955 (which was after the imposition of the Comic Book Code and not very publicized), in an article the Saturday Review of Literature called “It’s Still Murder: What Parents Still Don’t Know About Comics Books.” Reading more like a rant, Wertham accuses the Comics Book Code of not being sufficient and the Association (and comic book industry) of being disingenuous.

The code itself is a pious document. Liquor advertising is forbidden. There never was any. The word crime “shall never appear alone on a cover.” It never did. “Divorce shall not be treated humorously.” Was it, ever? The code does not even mention narcotics and drug addiction, which have played such an infamous role in crime and love comics. Pools of blood are not mentioned either…. The Code does not forbid cruelty to children…. Kicking in the face, popularized in comics and never practiced by children before the comic book era, is not mentioned in the code…

Wertham continues his rant, advocating for further censorship:

In the wording of the code, Mr. Murphy [a reference to New York Magistrate Charles F. Murphy, the first head of the organization] has tipped his hand, too. “excessive violence is forbidden.” Should not all violence be toned down? “Brutal” torture is forbidden. Does that mean that refined torture is all right? “Excessive” knife and gunplay are forbidden; so is “unnecessary” knife and gun play. Does that mean that it is all right to stab a guy if need be? Surely this is not a countermeasure, but a cover-up continuation of the cruelty-for-fun education of children.

Wertham next goes through several examples in code-approved books. It is important to mention that not one of the examples feature Superman. Wertham concludes the article with an impassioned plea that comics should be legislatively eliminated:

At present, it is far safer for a mother to let her child have a comic book without a seal of approval that one with such a seal. If comic books, as the industry claim, are the folklore of today, then the codes are the fables. The problem is really simple. You either close down a house of prostitution or you leave it open. You can’t satisfy both those who want it open and those who want it closed. How long are we supposed to wait for the comics clean-up? Mr. Murphy told the Joint Legislative Committee: “It will take years and years.” It could be done in a few weeks. The way the industry acts, it seems to me that it will take centuries.

Wertham further argues for legislation that censors comic books:

Mammon is at the root of all this. The comic-book publishers, racketeers of the spirit, have corrupted children in the past, they are corrupting them right now, and they will continue to corrupt them unless we legally prevent it. Of course, there are larger issues in the world today, and mightier matters to be debated. But maybe we will lose the bigger things if we fail to defend the nursery.

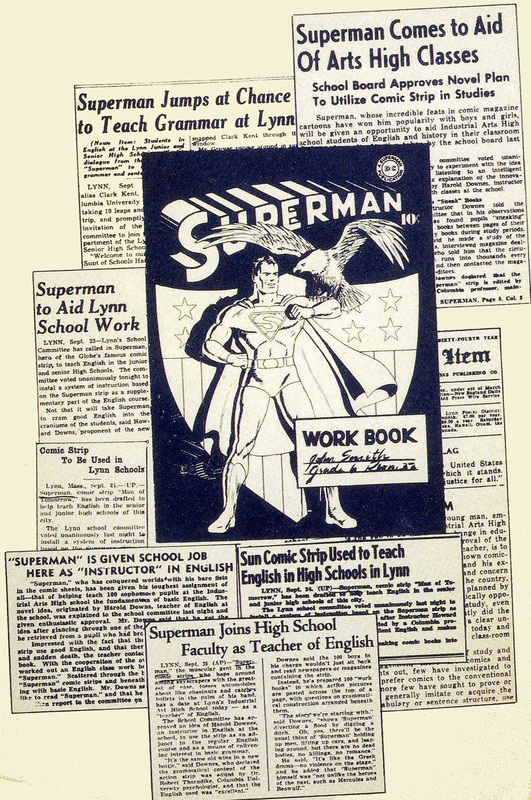

But it was too late. The battle was over. DC’s steps to keep Superman wholesome, combined with the serials, the radio program, the animated movies, the newspaper strips, and the brand new television show, made the character more popular than ever. Moreover, Wertham’s attacks actually had the reverse effect and made the Superman comics more appealing to rebellious children since it was portrayed as forbidden fruit. Parents and educators took advantage of this by having the character appear in workbooks to teach grammar, vocabulary and spelling. But, perhaps the greatest sign that Superman had emerged unscathed came in the 1960s when the Kennedy administration approached DC to create a book to promote exercise. Like Superman, President Kennedy had utilized the fledging television medium to help attain iconic status. Together, the two helped close the “muscle gap” with “Superman’s Mission for President Kennedy!” Tragically, the issue was delayed when, in November 1963, President Kennedy fell to an assassin’s bullet.

But it was too late. The battle was over. DC’s steps to keep Superman wholesome, combined with the serials, the radio program, the animated movies, the newspaper strips, and the brand new television show, made the character more popular than ever. Moreover, Wertham’s attacks actually had the reverse effect and made the Superman comics more appealing to rebellious children since it was portrayed as forbidden fruit. Parents and educators took advantage of this by having the character appear in workbooks to teach grammar, vocabulary and spelling. But, perhaps the greatest sign that Superman had emerged unscathed came in the 1960s when the Kennedy administration approached DC to create a book to promote exercise. Like Superman, President Kennedy had utilized the fledging television medium to help attain iconic status. Together, the two helped close the “muscle gap” with “Superman’s Mission for President Kennedy!” Tragically, the issue was delayed when, in November 1963, President Kennedy fell to an assassin’s bullet.

The Krypton Companion (in an article entitled “Krypton Meets Camelot”) explains:

The most famous of the Chief Executive’s DC appearances was “Superman’s Mission for President Kennedy!” in Superman #170 (July 1964), which has an intriguing backstory. Planned for publication in issue #168 (cover date Apr. 1964) as part of the President’s campaign to encourage physical fitness among youths, “Superman’s Mission,” written by Bill Finger and E. Nelson Bridwell, was originally drawn by Curt Swan. The story was shelved immediately after Kennedy’s November 22, 1963 assassination, but rescheduled for print upon the request of Kennedy’s successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson. Swan’s original pages were, according to conflicting reports either lost or given to Jacqueline Kennedy, and Al Plastino quickly stepped forth to render the tale for publication. Plastino’s artwork for this landmark story is displayed in the Kennedy Library.

As Superman’s popularity grew, Wertham soon became a pariah. Les Daniels explains in Comix, A History of Comic Books in America:

[The Comics Code Authority] proudly proclaimed itself the most oppressive force of censorship on the American landscape, and nobody batted an eyelash. In addition, it even managed-to provide an indignant scapegoat: Dr. Wertham. The irony is while Wertham was the clever and coherent of the comics critics, he most certainly was not connected with the Authority.

I should also add that, perhaps in response to frustration with the success of the Superman show, Wertham attempted to “clean up” early television by writing an anti-televisual thesis, War on Children (1959), which was very similar in theme to Seduction of the Innocent. The book could not find a publisher.

In short, Wertham’s cultural influence waned as Superman’s grew.

Still, Wertham tried to move on, all the while denying that he was pro-censorship or against comic books. He stated:

My main interest is not in comic books or even mass media, but in children and young people. Over the years I have been director of large mental hygiene clinics… And I have done a great deal of work — sometimes with great difficulty — to prevent young people from being sent to reformatories where they are often very badly treated. I have also helped a number of young people so they were not sent to the electric chair. Seeing that so many immature people have troubles and get into trouble, I tried to find out all the sources that contributed to their difficulties. In the course of that work I came across crime comic books. I had nothing whatever to do directly with the comics code. Nor have I ever endorsed it. Nor do I believe in it.

Wertham further argues that his actions were not censorship, but intended to protect children. He even notes that he testified against censorship in federal court. In the 1970s, Wertham even wrote a book applauding the subculture of comic fandom, The World of Fanzines (1974), where he concluded that fanzines were “a constructive and healthy exercise of creative drives.” Trysh Travis writes in Romanticizing the Comics: What Wertham Got Right (featured in a 2012 issue of Raritan, A Quarterly Review):

In the post-Code years, Wertham routinely received hate mail from comics fans who, like Trombetta [author of The Horror! The Horror! Comic Books the Government Didn’t Want You to Read!], believed that his Senate testimony was “the day comics died.” Because he thought the Code was stupid and ineffective, because he was in fact a lifelong opponent of censorship, and because he seems to have been a remarkably principled and decent man, Wertham made a habit of responding to these letters. His dialogue with fans led him to write, in 1973, The World of Fanzines: A Special Form of communication. Though hardly a great book, Fanzines nevertheless suggests how we might move away from an overdetermined narrative of pop-culture creators, consumers, and forms as “cultural insurgents” (David Hajdu’s term) to construct a more precise, if less anthemic, account of how and why popular art forms matter — as well as of the limitations on that mattering.

Wertham’s work on the World of Fanzines earned him an invitation to address the New York Comic Art Convention, where, as expected, he faced a hostile crowd and was heckled.

As a result, Wertham never wrote about comics again.

So who won?

Isn’t it obvious?

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this bymaking a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net/.

Superman is (c) DC Comics.