Welcome to Using Graphic Novels in Education, an ongoing feature from CBLDF that is designed to allay confusion around the content of graphic novels and to help parents and teachers raise readers. In this column, we examine graphic novels, including those that have been targeted by censors, and provide teaching and discussion suggestions for the use of such books in classrooms.

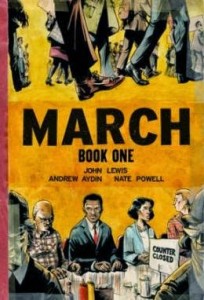

In this post, we take a closer look at March: Book One by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell (Top Shelf, 2013). We highlight it here as it sensitively documents Americans’ struggle for equal rights and civil liberties, and because this award-winning graphic novel is an excellent book to read, learn, and discuss for Black History Month.

March: Book One begins the trilogy of Representative John Lewis’s graphic novel memoire, co-written with his aide Andrew Aydin and illustrated by Nate Powell. It is a critically acclaimed best-seller that received the 2013 Coretta Scott King Honor Book Award by the American Library Association and has been named one of the best books of 2013 by USA Today, The Washington Post, Publishers Weekly, Library Journal, School Library Journal, Kirkus Reviews, The Horn Book, ComicsAlliance, and others.

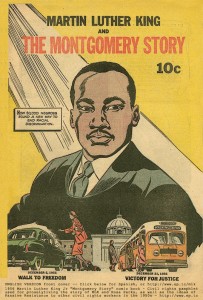

March: Book One recounts Congressman Lewis’ youth in rural Alabama and provides a wonderful window into what life was like for Black families in the 1940s and 1950s under Jim Crow and segregation laws. Lewis’ first-person narrative allows him to reminisce as he revisits his past, while the prose and art give us the feeling that we, too, are reliving this tumultuous time in American history along with him. Together, we are introduced to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s words and speeches, and we learn of the birth of the Nashville Student Movement and their non-violent struggle to eliminate segregation through their lunch counter sit-ins and their trips to prison and City Hall. We learn of Lewis’ first meeting with Dr. King and about the Supreme Court school desegregation decision of Brown v. The Board of Education. We learn about the case of Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi, of Rosa Parks and Jim Lawson and F.O.R. (Fellowship of Reconciliation), the last of which published Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a comic book that deeply influenced Lewis and so many more.

Table of Contents

BOOK OVERVIEW

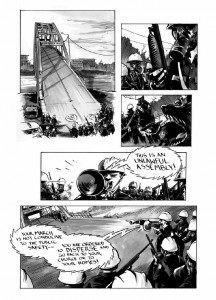

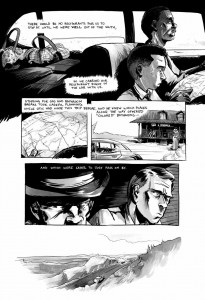

March: Book One opens with the march at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, during which 600 peaceful demonstrators were attacked by Alabama state troopers under the orders of then-governor George Wallace. The story then goes back and forth between shaping events in Lewis’ life that led to his being on the dais for Barack Obama’s 2009 inauguration. As Lewis and Aydin gently narrate Lewis’ story, the power of these events and the tumultuous emotions and reactions they evoked are relayed through Powell’s powerful images.

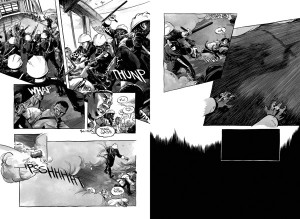

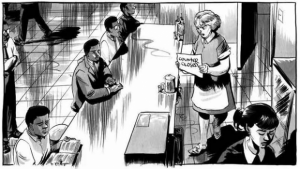

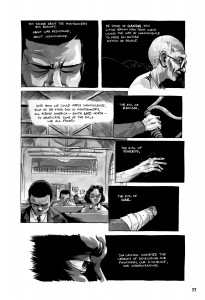

Powell’s black and white images empower viewers to comprehend those volatile times as we intimately view their unfolding events. Powell deftly uses contrast, negative space, sharp angles, and lettering to relay violent emotions, combining them with soft, sloping grays for the gentler intervals. There are beautiful wide-angle shots establishing historic locations, and sharp, angular lines, along with extensive use of black and white color juxtapositions to relate Lewis’ personal turmoil and the drama of these famous and infamous events.

Lewis’s Story

Even before the title page, the book opens with the Selma to Montgomery March in 1965. The images show peaceful protesters on the Edmund Pettus Bridge as they meet with angry, tear-gas-armed police officers. These images set the stage, letting us know that we will be marching with Lewis on his political and historical journey.

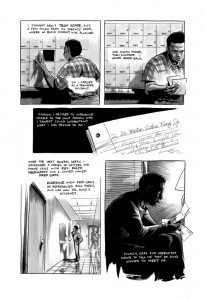

Following this introduction, the story moves back and forth between Lewis preparing to sit on a cold dais in wintery Washington D.C. for the 2009 Obama inauguration and the events in his life that led him there. While in his office before the inauguration, Lewis is joined by a small group of friends and constituents who ask him questions that enable him to reflect upon his past. Lewis’ first-person narrative is told with insight and sensitivity.

He begins his story with his childhood growing up on his parents’ tenant farm in rural Alabama, where he cared for their chickens. He named each one, and addressed sermons to his devoted “flock.” One fateful summer in the early 1950s, his Uncle Otis came to take him on a trip to Buffalo, New York. This opened Lewis’s eyes to the racial and social injustices of segregation and demeaning Jim Crow laws. On their drive north, Lewis describes their having to use “colored-only” bathrooms, the fact that they couldn’t stop at restaurants anywhere along the way, and that Blacks coming south from the north faced even greater perils. Upon his return from Buffalo, Lewis began noticing segregation and civil injustices in his town as Black kids rode to school in older busses, rural Black communities lacked paved roads, and Black students were given older texts books and playground equipment.

As Lewis grew, he became increasingly aware of segregation and racial injustice. In May 1954, he notes:

I read a headline that just turned by world upside-down. The U.S. Supreme court had handed down its decision in the school desegregation case of Brown vs. the Board of Education of Topeka. The doctrine of “separate but equal” — upon which the entire institution of segregation was based — had been ruled unconstitutional.

Then, one Sunday morning in early 1955, Lewis heard Martin Luther King’s radio sermon relaying the power of “social gospel.” Shortly after the speech, there was a second Supreme Court Ruling in Brown vs. The Board of Education, and as Lewis notes, “Lines had been drawn. Blood was beginning to spill,” sharing the Emmett Till murder in Money, Mississippi, as one example.

Fourteen-year-old Emmett, who was severely beaten and whose body was later found in the Tallahatchie River, was visiting relatives from Chicago. A black farmer, Moses Wright, witnessed two white men dragging Emmett from his relatives’ home and testified against them in open court. The all-white jury found the defendants not guilty, and while they confessed to the murder in Look Magazine a few months later, they had already been tried and nothing could be done against them.

We then read about Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Improvement Association-led boycott against the buses that discriminated against Parks.

Five days before Lewis’ sixteenth birthday, he preached his first public sermon and an article in The Montgomery Advertiser was published about the boy preacher. Shortly thereafter, his mother found out about a school in Nashville for Black men and women wishing to become ministers or missionaries. Lewis applied and was accepted. At one point, however, Lewis notes, “Here I was reading about justice, when there were brave people out there working to make it happen.”

Lewis contemplated applying as a transfer student to Troy State, near his parents’ home, which had not accepted any Black students. He discussed his thoughts of applying to Troy State with Rev. Ralph Abernathy, who referred him to lawyer Fred Gray, who represented Rosa Parks and Dr. King. After an exchange of letters, Lewis met with Dr. King and Mr. Gray, who agreed to help Lewis with the application process should he decide to apply and fight the admissions committee. They warned him, however, of dangers he and his family would be facing. After much thought, Lewis decided not to apply and remained in Nashville.

A greater influence upon Lewis’ life and path occurred March 26, 1958, when Lewis met Jim Lawson, a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (F.O.R.) who was conducting a workshop on non-violence. The F.O.R. trained people in ways of pacifism and non-violent demonstrations and was a major influence in the civil rights protests of the 1960s. Lewis relates the power and scope of the F.O.R. training, and his role in the Nashville lunch counter sit-ins held in downtown department stores hat refused to serve Black or inter-racial groups of customers.

As the sit-ins grew in numbers and incidents, reactions grew stronger and stronger. The peaceful protesters met with increasing arrests and court convictions. The protests continued and led to the city’s formation of a biracial committee to study segregation. Jim Lawson was fired from Vanderbilt, an act that in turn backfired due to widespread negative reactions nationally. The inaction of the committee led to further sit-ins, greater news coverage, and the eventual proposal of a system of partial integration. But the sit-ins continued, as did the violent reactions to the sit-ins. Finally, six downtown Nashville department stores began serving food to black patrons on May 10, 1960. So ends Lewis’ story in March: Book One.

To help readers more fully understand the time period, Lewis, Aydin, and Powell sensitively relate how painful this era was for everyone, without casting aspersions. Lewis narrates the pivotal events in his life through gentle conversation while Powell’s art leaves us to interpret and feel his their resulting emotions and consequences.

In short, Lewis’s story is told through gentle narration and vibrant art, in a way that empowers us to relive it with him. As a result, readers better understand the suffering and angst of segregation and Jim Crow laws that led to the 1960s civil rights movement.

Throughout March: Book One, Lewis, Aydin, and Powell relay:

- The effects of segregation and the Jim Crow laws in the 1940s – 1960s;

- The background and series of events leading the Civil Rights Movement;

- The effects of racism and blind acceptance of “fact” and of accepted status-quo;

- A community’s coming of age in its struggle for civil rights;

- The development of local and of national heroes and understanding how these heroes come to be;

- The power of the peoples’ voice in a democratic republic;

- The powers and limits of local and national government, especially in times of civic unrest;

- The power of social gospel and non-violent protest in times of civic unrest;

- The struggles nations and individuals must endure when fighting for their principles and ideals;

- The different ways people find the courage to stand up and fight for their rights;

- The power words (whether through books, newspapers or oratory) can have.

NOTE: According to Top Shelf Publishing, March: Book Two will be released in December. They are also planning a physical reprint of Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story. Originally published in 1957-58 by F.O.R., F.O.R. and Top Shelf recently made Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story available exclusively through comiXology as part of a digital bundle with March: Book One or as a stand alone download. F.O.R. will be publishing a physical reprint and releasing it on April 30,, and proceeds will go towards F.O.R.’s work promoting nonviolence around the world.

TEACHING/DISCUSSION SUGGESTIONS:

For Black History Month

- Research and review the Jim Crow laws that were in effect in Alabama in the 1950s and/or research and review the Jim Crow laws observed by your local/state community in the 1950s.

- Discuss the concept of “Separate but Equal”: it’s intent, its applications, and how it hurt so many. (See below for links to relevant resources.)

- Research and discuss how the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. The Department of Education was received among different communities (White and Black, north and south), and discuss its ramifications. (See below for links to relevant resources.)

- Research and discuss the March at Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965. (See below for links to relevant resources.) Discuss:

- What marchers went through just to get there;

- Whether or not they were expecting any trouble;

- Different ways people reacted and reported this incident.

- Review and discuss Martin Luther King Jr.’s radio speeches.

- Review and discuss the F.O.R. publication of Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story. Why do you thing this so influenced the young John Lewis and so many of his peers?

- Research and discuss what it meant to be a tenant farmer and sharecropper in the 1940s and 1950s . Where there differences for Black and White farmers?

Cultural Diversity, Civic Responsibilities, and Social Issues

- Analyze how the book’s different characters dealt with racism. Ask students how they might deal with racist comments, practices, and restrictions.

- Discuss what it must have felt like to be excluded from busses and shops and from receiving community services.

- Discuss different options and means of protest. How have these options changed today compared to the options Lewis and his colleagues had in the 1960s?

- Research, present, and discuss the personal backgrounds, public struggles, and the articles and speeches of local and national figures of the Civil Rights Movement.

- Define and discuss “racism”

- Discuss the different instances of discrimination and racism presented throughout the book. Discuss instances of racism today on local, national and international scenes.

- How is it the same/different across time and geographic locations (nationally and/or internationally)?

- How has racism changed today, if at all?

- Discuss the different instances of discrimination and racism presented throughout the book. Discuss instances of racism today on local, national and international scenes.

- Discuss how hurtful racism can be — to those targeted as well as to the general population.

- Discuss how racism has influenced, shaped and determined national and international policies and politics.

- Discuss what can be done today to fight racism and discrimination and ways students can help.

Language, Literature, and Language Usage

- Search for, define, and discuss slang and idioms that were used to demean Blacks. Compare and contrast these words to words used today to demean Blacks, Whites, Jews, Asians or any other “different” culture.

- Search for, define, and discuss the book’s use of idioms, hyperbole, and simile to better express opinions, feelings, and cultural expressions. Discuss how effective they are in communicating a specific message or a specific point in time. For example, you may want to discuss:

- On page 38, Lewis notes, “we carried our restaurant right in the car with us.”

- On page 42, “I was about ready to burst with excitement.”

- On page 53, “I was certain he’d tan my hide.”

- On page 56, “Dr. King’s message hit me like a bolt of lightning…Lines had been drawn, blood was beginning to spill.”

- On page 109 “Cut off the head, the thinking went, and the body would fall.”

- Have students collect family stories (oral, written, and/or photographed) of the 1960s and civil rights movement, marches, and protests, and/or stories of racism and segregation. (Note: There were and still are incidents of racism and segregation experienced by minority and immigrant families as well. To include all your students, you may want to expand your discussion/project to the comparing and contrasting racist incidents directed at various targeted groups.)

- You may have students write two versions of these stories as a means of reflecting on language use and idioms that are time/era specific. Have them write one version as if they are there in the 1960s as a first-person narrative, and then have them write it s if they are reflecting back. from now How does the language and/or the story differ?

Critical Thinking and Inferences

The authors make many inferences in this book both with language use and through imagery. You may want to discuss the following uses of inference:

- On page 1, we see people walking on the Edmund Pettus Bridge and the first words we read are: “Can you swim?” Discuss why these are actually very powerful words to begin with. You may also want to discuss the metaphor these words relate and the inferences they evoke.

- When Lewis talks about his trip with his Uncle Otis to Buffalo, New York, he writes (p. 37): “I know now that Uncle Otis saw something in me that I hadn’t yet seen. THAT is why we took our trip in June of ’51.” Discuss what is was Uncle Otis saw in young John Lewis.

- On page 47, Lewis relates that after his trip with Uncle Otis, “I started riding the bus to school, which should’ve been fun. But it was just another sad reminder of how different our lives were from those of white children.” Compare and contrast:

- The lives of black and white children in Alabama in the 1950s;

- The lives of black children in the north and south of the U.S. in the 1950s;

- The lives of black and white students in the 1950s versus the lives of black and white students today.

- On page 70, Lewis relates that upon first meeting Dr. King, Lewis said, “Dr. King, I am John Robert Lewis. I said my whole name.” Discuss why Lewis used his full name here and the impact it had on everyone at that meeting.

- Discuss what Lewis meant on page 109, where he notes, “That same day, the Chancellor and Trustees of Vanderbilt University ordered the Dean of the Divinity School to dismiss Jim Lawson. Cut off the head, the thinking went, and the body will fall.”

Modes of Storytelling and Visual Literacy

In graphic novels, images are used to relay messages with and without accompanying text, adding additional dimension to the story. Compare, contrast, and discuss with students how images can be used to relay complex messages. For example:

- Have students hunt for visual and verbal examples of racism, discrimination, and /or segregation, comparing how they are relayed through language and how they are relayed through image. Discuss the impact of these various forms of communication.

- For parts of the story, Powell relays his images against a black background while others are relayed against a white background. Chart when he does each and discuss why this might be. Discuss how page design and backgrounds help communicate the story and its messages.

- On page 9, Powell uses color and angles to relay the violence on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Explore how he does this and the emotions and impressions these images create.

On page 27, Lewis notes that “By the time I was five I could read it (the Bible) myself, and one phrase struck me strongly, though I couldn’t comprehend its full meaning at the time….’Behold the lamb of God which taketh away the sin of the world.’” Discuss how the image Powell draws influences the meaning of Lewis’ worlds.

On page 27, Lewis notes that “By the time I was five I could read it (the Bible) myself, and one phrase struck me strongly, though I couldn’t comprehend its full meaning at the time….’Behold the lamb of God which taketh away the sin of the world.’” Discuss how the image Powell draws influences the meaning of Lewis’ worlds.- Compare and contrast how the authors help us distinguish between words that were sung, spoken, preached, and/or heard over the radio.

- Discuss how Powell uses art between pages 60-63 to relay the passage of time in Lewis’ life and narrative.

Suggested Prose Novel and Poetry Pairings

For greater discussion on literary style and/or content here are some prose novels and poetry you may want to read with March: Book One

- The Silence of Our Friends by Mark Long, Jim Demonakos and Nate Powell (First Second Books, 2012) — A semi-autobiographical story of Mark Long’s childhood experiences in Houston, Texas, 1968 centering around the Texas Southern University student boycott after the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCCC) was banned from its campus.

- P.S. Be Eleven (winner of the Loretta Scott King Award, 2013) and sequel to One Crazy Summer (Newbery Honor Book) by Rita Williams-Garcia — Both novels reveal race, gender and political issues of the late 1960s.

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee — An American classic about a town struggling with racism and a trial that brings two families from opposing sides of the civil rights conflict to the forefront.

- I Have a Dream: Writings and Speeches That Changed the World by Martin Luther King Jr. — Martin Luther King, Jr.’s text of his famous speech (see its link below).

- Martin’s Big Words: The Life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. by Doreen Rappaport and Bryan Collier (illustrator) — An extraordinary picture-book biography incorporating narrative, famous quotes from Dr. King, and powerful collage and watercolor illustrations that introduce King’s words and legacy to younger readers.

- Coming of Age in Mississippi by Anne Moody — An autobiography of a poor black girl whose parents were tenant farmers on a Mississippi plantation and whose dream of going to college was realized upon winning a basketball scholarship. We get first-hand accounts of her joining the NAACP, CORE, and SNCC and the steps she took in demonstrations, and sit-ins, along with her subsequent arrests and jailings.

- Through My Eyes: Ruby Bridges by Ruby Bridges, Margo Lundell (Editor) — Ruby Bridges chronicles her steps in November 1960 as a six-year-old black girl surrounded by federal marshals who walked through a mob of screaming segregationists into her school.

Common Core State Standards

March: Book One is full of advanced vocabulary, simile, slang, idioms, and cultural folklore. It promotes critical thinking, introduces multiple national American Heroes, and is a coming of age story laden with issues of identity, justice and friendship. Furthermore, in graphic novel format, it provides verbal and visual story telling that addresses multi-modal teaching, and meets Common Core State Standards including:

- Key ideas and details: Citing textual evidence, determining a theme or central idea, describing how a plot unfolds, analyzing how particular elements of the story interact; analyzing how particular lines of dialogue or incidents of a text reveal aspects of a character or provoke a decision; analyzing a particular point of view or cultural experience reflected in a work of literature from outside the United States, drawing on a wide reading of world literature.

- Craft and structure: Determining the meaning of words and phrases including figurative and connotative meaning; analyzing how particular sentences, chapters, scenes or stanzas fit into the overall structure of a text; explaining how a point of view is developed; analyzing how a text’s structure or form contributes to its meaning; analyzing a particular point of view or cultural experience reflected in a work of literature from outside the United States, drawing on a wide reading of world literature; determining the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to domains related to history/social studies; describing how a text presents information

- Integration of knowledge and ideas: Comparing and contrasting texts; distinguishing among fact, opinion, and reasoned judgment in a text; analyzing how a modern work of fiction draws on themes, patterns of events, or character types from myths, traditional stories, or religious works describing how the material is rendered new; analyzing how an author draws on and transforms source material in a specific way..

- Range of reading and level of text complexity: By the end of the year, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, in the grades 6-8, and in the grades 8-10 text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

- Knowledge of language: Using knowledge of language and its conventions when writing, speaking, reading, or listening; applying knowledge of language to understand how language functions in different contexts, to make effective choices for meaning or style and to comprehend more fully when reading or listening.

- Vocabulary acquisition and use: Determining the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases; demonstrating understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in world meanings; and acquiring and using accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases.

- Research to build and present knowledge: Drawing evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research;

- Comprehension and collaboration: Engaging effectively in a range of collaborative discussions building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly.

- Presentation of knowledge and ideas: Presenting claims and findings, sequencing ideas logically and using pertinent descriptions, facts, and details to accentuate main ideas or themes.

This book and related discussions also cover the following themes identified by The National Council for the Social Studies:

- Culture and Cultural Diversity: “…students need to comprehend multiple perspectives … to consider the strengths and advantages that this diversity offers to the society in general and to their own growth…to analyze the ways that a people’s cultural ideas and actions influence its members…”

- Time, Continuity, and Change: “…facilitate the understanding and appreciation of differences in historical perspectives and the recognition that interpretations are influenced by individual experiences, societal values, and cultural traditions… examine the relationship of the past to the present and extrapolating into the future… provide learners with opportunities to investigate, interpret, and analyze multiple historical and contemporary viewpoints within and across cultures related to important events, recurring dilemmas, and persistent issues, while employing empathy, skepticism, and critical judgment…”

- Individual Development and Identity: “…describe how family, religion, gender, ethnicity, nationality, socioeconomic status, and other group and cultural influences contribute to the development of a sense of self…have learners compare and evaluate the impact of stereotyping, conformity, acts of altruism, discrimination, and other behaviors on individuals and groups…”

- Individuals, Groups, and Institutions: “…help learners understand the concepts of role, status, and social class and use them in describing the connections and interactions of individuals, groups, and institutions in society…analyze groups and evaluate the influence of institutions, people, events, and cultures in both historical and contemporary settings…identify and analyze examples of tensions between expressions of individuality and efforts of groups and institutions to promote social conformity…”

- Power, Authority, and Governance: “…understanding the historical development of structures of power, authority, and governance and their evolving functions in contemporary American society… enable learners to examine the rights and responsibilities of the individual in relation to their families, their social groups, their community, and their nation… examine issues involving the rights, roles, and status of individuals in relation to the general welfare…explain conditions, actions, and motivations that contribute to conflict and cooperation within and among nations…challenge learners to apply concepts such as power, role, status, justice, democratic values, and influence…”

- Civic Ideals and Practices: “…assist learners in understanding the origins and continuing influence of key ideals of the democratic republican form of government, such as individual human dignity, liberty, justice, equality, and the rule of law…analyze and evaluate the influence of various forms of citizen action on public policy…evaluate the effectiveness of public opinion in influencing and shaping public policy development and decision-making…”

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

- March: Book One Teacher’s Guide (which is quite good) can be downloaded at http://www.topshelfcomix.com/contact/teachers-guidehttp://www.topshelfcomix.com/contact/teachers-guidehttp://www.topshelfcomix.com/contact/teachers-guide

- Information on the Edmund Pettus Bridge and the Selma-to-Mongomery March of 1965

- Background on the Emmett Till murder

- PBS’ American Experience: The Murder of Emmett Till — Contains the killers’ confessions admitting their guilt; a synopsis and transcript of this film; a link for primary sources (including family letters and reactions to the murder); and further readings; a timeline; teacher’s guide; and more.

- Separate is not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education – resource material provided by the Smithsonian National Museum of American History – with links to other important milestones in the civil rights movement.

- PBS’ American Experience: Civil Rights Movement Non-Violent Protests — Contains related videos, photographs, interviews, press coverage and primary sources, milestones, reflections, notes for teachers, and more.

- http://www.pbs.org/jefferson/enlight/brown.htm — Contains links and details of the Brown v. Board of Education decision

- Martin Luther King, Jr. I Have a Dream speech (text and audio)

- http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/themes/civil-rights/exhibitions.html — Multimedia resources from the Library of Congress that support the teaching about civil rights

- Historical places of the civil rights movement — We Shall Overcome: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary, with an introduction, itinerary maps, list of sites and links to learn more.

- http://www.academicinfo.net/africanamcr.html — Civil rights history resource

- http://www.pbs.org/teachers/thismonth/civilrights/index1.html — Teaching ideas for teaching the civil rights movement in American literature (all grade levels)

- http://www.crmvet.org/poetry/poemhome.htm — Poems of the Freedom Movement

- http://www.whyy.org/generations/oral.html — Guide for students on how to conduct oral history interviews, with samples of American slave narratives and other primary resource sets

- http://www.history.com/search?q=civil+rights+movement&x=0&y=0 — History Channel list of links and resources

- http://www.goodreads.com/shelf/show/civil-rights-movement and http://www.slj.com/2013/01/books-media/collection-development/focus-on-collection-development/civil-rights-everyday-heroes-focus-on-january-2013/ — Provide extensive lists for further reading on the Civil Rights Movement for students of varying ages and reading levels.

Meryl Jaffe, PhD teaches visual literacy and critical reading at Johns Hopkins University Center for Talented Youth OnLine Division and is the author of Raising a Reader! and Using Content-Area Graphic Texts for Learning. She used to encourage the “classics” to the exclusion comics, but with her kids’ intervention, Meryl has become an avid graphic novel fan. She now incorporates them in her work, believing that the educational process must reflect the imagination and intellectual flexibility it hopes to nurture. In this monthly feature, Meryl and CBLDF hope to empower educators and encourage an ongoing dialogue promoting kids’ right to read while utilizing the rich educational opportunities graphic novels have to offer. Please continue the dialogue with your own comments, teaching, reading, or discussion ideas at meryl.jaffe@cbldf.org and please visit Dr. Jaffe at http://www.departingthe text.blogspot.com.

We need your help to keep fighting for the right to read! Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

All images (c) John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell