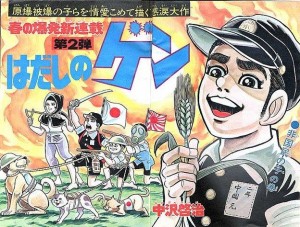

Keiji Nakazawa’s internationally renowned manga Barefoot Gen, which depicts wartime atrocities from the perspective of the seven-year-old protagonist, has fallen victim to several challenges in its home country of Japan. Barefoot Gen is loosely based on Nakazawa’s own childhood, as his father, two sisters, and a brother were killed in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima when he was seven years old. Nakazawa died of lung cancer last year, but his widow Misayo said he felt strongly “that he must share with children accounts of the miseries of the war and the atomic bombing to prevent a recurrence.” To aid in this effort, he donated 2,735 original drawings from the manga and 30 boxes of other materials to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Keiji Nakazawa’s internationally renowned manga Barefoot Gen, which depicts wartime atrocities from the perspective of the seven-year-old protagonist, has fallen victim to several challenges in its home country of Japan. Barefoot Gen is loosely based on Nakazawa’s own childhood, as his father, two sisters, and a brother were killed in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima when he was seven years old. Nakazawa died of lung cancer last year, but his widow Misayo said he felt strongly “that he must share with children accounts of the miseries of the war and the atomic bombing to prevent a recurrence.” To aid in this effort, he donated 2,735 original drawings from the manga and 30 boxes of other materials to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Tomoko Watanabe of the nonprofit peace group ANT-Hiroshima said that Nakazawa’s message successfully connected with young readers: “The work does describe brutal scenes, but children are intrinsically able to get to the essence of the story — that people should live despite the difficulties. We must trust the children and let them read as they want to.” Instead, Matsue officials apparently prefer to shield students from real-life events and risk the realization of Nakazawa’s worst fear for a new generation.

The book shows bomb victims “with their skin rotting and falling off their bodies…while others are seen dismembered,” but it also does not shy away from atrocities committed by Japanese troops in other Asian countries. It was these events, such as the Rape of Nanking and “a publicized account of two soldiers aiming to kill 100 Chinese citizens first in a contest,” that caused a Matsue citizen to challenge the book’s presence in schools. Many Japanese nationalists deny that such war crimes were ever committed by their country’s troops. Matsue’s board of education did not address the history revisionism behind the challenge, but instead said that the manga may be too graphically violent for children to read on their own.

The series was pulled from primary and middle school libraries in the Japanese city of Matsue. Keiji Nakazawa’s celebrated series was removed after the complainant — one who does not even live in the prefecture where Matsue City is located — called the book an “ultra-leftist manga that perpetuated lies and instilled defeatist ideology in the minds of young Japanese.” Citing “portions that warrant consideration as appropriate reading material for children,” school officials barred students from checking out the manga but allowed teachers to continue using it in classrooms. The Matsue City school board overturned the order that banned Barefoot Gen from school libraries, but they didn’t do it over concerns of censorship. The board cited concerns over procedural problems with the decision.

A little more than a month after Keiji Nakazawa’s manga classic Barefoot Gen was restored to school libraries in Matsue, an English-language translator of the series has been abruptly disinvited from speaking at a junior high school in suburban Tokyo, 400 miles away. School officials there obliquely cited “recent circumstances” and “social trends” as their reason for cancelling the translator’s visit.

In early 2014, a mayor in Izumisano City in the Osaka Prefecture, Japan, demanded that all copies of Barefoot Gen be removed from elementary and junior high schools in the district. Izumisano City’s mayor, Hiroyasu Chiyomatsu, felt compelled to review the manga after it was temporarily banned in Matsue City. Chiyomatsu called for the removal in Izumisano City because he feels that the book discriminated against the mentally ill and poor. The district has eight elementary schools and five junior high schools, so the ban affected a relatively large number of students.

After Chiyomatsu expressed concern in November about “many expressions in the manga that impact human rights,” his political ally and appointee Tatsuhiro Nakafuji, superintendent of Izumisano schools, passed a resolution to collect all 128 copies of the book from district libraries. Many schools refused to cooperate, however, so in January, Nakafuji personally collected the remaining copies. Following this action, the local school principals’ association sent two letters of protest to the school board, saying that “[t]o deny children the chance to read the manga grounded in [a] certain sense of values and ideas is a violation of their human rights.”

In response to media coverage and protests from educators and citizens, the school board claimed that it had planned all along to only withhold the books until March 20, after making “preparations to provide guidance to students regarding the problematic expressions.”