Translator and manga industry expert Dan Kanemitsu submitted the following opinion piece on the recent ban of Barefoot Gen from the perspective of being close to the ground in recent battles involving manga regulation in Japan.

Translator and manga industry expert Dan Kanemitsu submitted the following opinion piece on the recent ban of Barefoot Gen from the perspective of being close to the ground in recent battles involving manga regulation in Japan.

In December of 2010, Tokyo was buzzing over the revision of an ordinance that regulates what can be considered harmful to youth and restricts the circulation of such material. While touted by advocates as a simple age restriction stipulation, the labeling of works as “harmful to youth” and thereby making them available only for adults had effect of driving many books out of print. Books demarcated as being harmful were shunned by the distribution system, and thus the label was considered a kiss of death. This was one of the reasons why the manga publishing industry in Japan fought the revision attempt so bitterly.

The second revision attempt of the Tokyo Metropolitan Ordinance Regarding the Healthy Development of Youths was designated Bill 156, and during the public debate regarding this bill, the then deputy Governor of Tokyo, Naoki Inose, pressed on-line for the passage of the new expansion of what constitutes “harmful to youth.” He claimed that the new bill was merely a provision which would more effectively restrict the sales of problematic works to minors and nothing more.

When pressed on the question of how previously published works would fare under the new expanded definition, Mr. Inose claimed that masterpieces by Osamu Tezuka and others would be just fine under Bill 156. Mr. Inose, who has since become the Governor of Tokyo, at the time contended that people should not blame the revision of the ordinance for their inability to create masterpieces, going on to state that “if you create a masterpiece, the ordinance will be pushed back.”

The clear implication here is that the restrictions on manga and anime was directed toward what moralists considered sub-standard works that contribute the delinquency of youth or disgusting smut produced by unscrupulous authors and publishers who were flaunting the spirit of the ordinance.

But in fact, any work can fall prey to calls of restriction and censorship, and in some cases guardians entrusted with protecting works will cower to the most ridiculous of demands simply to avoid controversy, especially when fending off criticism becomes inconvenient and tiresome.

The standards of what constitutes ridiculous demands for censorship was raised considerably when the Japan Society for Tobacco Control claimed that Hayao Miyazaki’s latest film, The Wind Rises, was in violation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, an international treaty that includes guidelines on advertising related to smoking.

The outcry against this claim within Japan was very strong, where even advocates for reducing smoking were saddened that the society was making very precarious contention that a fictional film that was based in pre-war and wartime time period in Japan could be considered advertising for the contemporary tobacco industry.

The Japan Society for Tobacco Control has since modified their position slightly, now claiming that the depiction of characters smoking amounts to “product placement” and thereby should be curtailed because it encourage viewers to smoke cigarettes.

This controversy has been considered a wake-up call by many, making it clear that even masterpieces by giants of the anime industry are prone to calls of censorship. (Here are some more links to the debate raging in Japan: http://sankei.jp.msn.com/entertainments/news/130823/ent13082311310009-n1.htm and http://news.mynavi.jp/news/2013/08/21/023/).

So far the parties involved in the production and distribution of The Wind Rises have effectively ignored the calls for censorship of their film, but not everybody has shown equal determination to protect the integrity of masterpieces, never mind more “mundane” works.

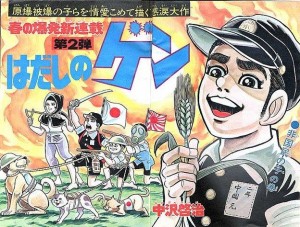

In August, news broke that Keiji Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen, a manga considered to be one of the best works ever regarding the Hiroshima atomic bombing and the subsequent turmoil of post-war Japan, was removed from libraries of Matsue City schools. Matsue City is part of Shimane Prefecture, located on Shikoku Island. It is considered to be a quiet, rural locality that is adverse to conflict. Compulsory education in Japan is only up to junior high school, so Matsue City’s decision to remove Barefoot Gen means grade school and junior high school students no longer have access to a book that has been on the bookshelves for decades.

In August, news broke that Keiji Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen, a manga considered to be one of the best works ever regarding the Hiroshima atomic bombing and the subsequent turmoil of post-war Japan, was removed from libraries of Matsue City schools. Matsue City is part of Shimane Prefecture, located on Shikoku Island. It is considered to be a quiet, rural locality that is adverse to conflict. Compulsory education in Japan is only up to junior high school, so Matsue City’s decision to remove Barefoot Gen means grade school and junior high school students no longer have access to a book that has been on the bookshelves for decades.

The decision to remove Barefoot Gen from an entire public school system’s libraries was a shock to many. Barefoot Gen has long been considered a staple of book collections for children. While its depictions are graphic, both the right wing and the left wing applauded how it portrayed the savage nature of war and how the Japanese suffered terribly from it. The right used Nakazawa’s work to attack the victor’s justice that was directed against Japan by Allies after the war, while the left celebrated Nakazawa’s work as an important reminder of how war should be avoided and the terrible decision making that lead to Japan’s defeat.

Many assumed that the books was removed from circulation because of complaints by local residents who were over-sensitive regarding the graphic depiction featured in the manga — which is something Nakazawa was unabashed about, claiming the one reason he created Barefoot Gen was to “un-glorify” war — but it turned out that the impetus for this decision was based on a complaint from someone who was not even a resident in the particular prefecture. (A prefecture is the Japanese equivalent of a US state.)

Chiki Ogiue, a radio show host who often takes up free speech issues, reported via Twitter on some of the background behind how access to Barefoot Gen became restricted. He uncovered that a single person repeatedly demanded that Barefoot Gen be removed from school libraries because the work was “a ultra-leftist manga that perpetuated lies and instilled defeatist ideology in the minds of young Japanese.” He threatened to distribute 500 copies of a booklet that exposed harmful effects of this “ultra-leftist anti-Japanese book full of falsehoods.” This same person also called for flying the flag of Kochi Prefecture and the Japanese flag above the Kochi Prefecture Assembly (a neighboring prefecture) and creating a Takeshima Education Reference Center. (Takeshima is an island currently occupied by South Korea that is claimed by Japan.)

The person’s petition was rejected by the Matsue board of education overwhelmingly, but superintendent reviewed the manga in question and decided to restrict access to Barefoot Gen because of its gruesome depictions of the chaos just before war ended and right after. The citizen who called for Barefoot Gen to be restricted reportedly rejoiced over this decision, since even though his logic was rejected, his call for restricting the book went forward nonetheless.

Recently, it was revealed that members of the local education board were not allowed to deliberate over removing Barefoot Gen from circulation, and that the decision to place the manga in the restricted stacks was unilaterally conducted by superintendent of education in Matsue, along with the administration bureau.

As news of how Barefoot Gen was being treated in Matsue spread, the superintendent and administration bureau went into a “deer in headlights syndrome.” They openly questioned why the issue come up months after the decision was reached, backpedaling on the gravity of its decision, stating that teachers still can use Barefoot Gen in the classroom and students still have access to it if teachers deem that the student is ready to read the book.

The decry against this decision has been thunderous, where Mainichi Shinbun newspaper has recently reported that over 90% of calls reaching out to the education department of Matsue City has been critical regarding its decision to restrict access to Barefoot Gen.

But none of this would have come to light had it not for the fact that someone noticed access to Barefoot Gen was restricted and that Barefoot Gen enjoys such widespread popularity in Japan.

Meanwhile, Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Minister Hakubun Shimomura has supported the superintendent decision to restrict access to Barefoot Gen, thereby turning a local issue into a national issue. Protecting the imagined vulnerable sensibilities of youth has now become justification for restricting access to a masterpiece that was available for children for decades.

And thus, we return to the stake first laid out by Mr. Inose and the question of which works deserve protection. I would argue that ANY work of fiction should deserve equal protection under freedom of expression. Many works start off relatively modest popularity. When Mobile Suit Gundam first aired, the popularity was so low that the toy sponsors forced Director Yoshiyuki Tomino to cut back on the duration of the television series. When Katuhiro Ootomo’s Akira first started serialization, few expected a manga featuring delinquent youth involved in hedonistic lifestyle in a dystopian Japan to evolve into a manga that would influence millions across the globe.

Freedom of expression should never be reserved for works that enjoy popular support nor works that are esteemed to be masterpieces by authority. These works already are buttressed by the mainstream society. Freedom of expression should be rigorously extended toward unpopular works, works that do not enjoy recognition by authority nor are sanctioned by the government.

This is not because we don’t know where the next masterpieces come from. It is because works made by ordinary people shared by even a few should enjoy the same protection works created by huge institutions make to be shared by millions. This is about democracy and diversity, not about protecting high culture at the expense of low culture.

Inconvenience is never a justifiable rationale for censorship.

Dan Kanemitsu is a translator, interpreter, and cultural reference consultant for Japanese culture. He blogs about manga, anime, and video games, frequently addressing attacks against free expression of these media in Japan and abroad. Mr. Kanemitsu played a key role in organizing CBLDF Executive Director Charles Brownstein’s Manga Freedom Speaking Tour in Japan. To learn more about his work as a translator, visit www.translativearts.com. Follow Mr. Kanemitsu’s blog at http://dankanemitsu.wordpress.com and follow him on Twitter @dankanemitsu.