Below is a web-friendly version of the CBLDF presentation on the history of comics censorship, which has been delivered to audiences of scholars, lawyers, advocates and readers in the United States. Please contact CBLDF about bringing this presentation to your group.

Born Banned

Censorship arising from moral panic is a constant presence in the history of comics. From the 1930s to the modern day, the comics medium has been stigmatized as low-value speech.

Moral crusaders asserted that comics corrupted youth, hurt their ability to read and appreciate art, and even made them delinquents. This kind of public criticism spread in popular magazines and town meetings, and even led to public burnings of comic books! Youth groups rallied to completely rid some towns of comics, buying up every comic in their local areas to be burned.

In the 1940s, comic book burnings were happening in the US, even as GIs were returning home from seeing the same activities in Germany. Although comics were associated primarily with juvenile readers, a full 25% of the printed materials going to military PXs in World War II were comics.

Sterling North’s anti-comics editorial, “A National Disgrace,” appeared in The Chicago Daily News in 1940. It was reprinted in multiple newspapers throughout the United States, and included quotes such as:

“Badly drawn, badly written and badly printed—a strain on young eyes and young nervous systems… Their crude blacks and reds spoil the child’s natural sense of color; their hypodermic injection of sex and murder make the child impatient with better, though quieter, stories.”

A Failed Attempt

The Association of Comics Magazine Publishers (ACMP) formed in 1948 to help curb this public criticism. The ACMP Code banned depictions sympathetic criminals, scenes of sadistic torture, the humorous or glamorous depiction of divorce, foul language, or ridicule or attack on religious or racial groups.

The ACMP failed due to a lack of uniform participation and standards for reviewing comics. The public criticism of comics continued.

Dr. Fredric Wertham

Fredric Wertham was a child psychologist who did groundbreaking work with underprivileged youth, but Wertham sullied his legacy in a quest for fame that manifested in the 1954 anti-comics screed Seduction of the Innocent. He is now known as one of the most iconic censors in modern history.

Fredric Wertham was a child psychologist who did groundbreaking work with underprivileged youth, but Wertham sullied his legacy in a quest for fame that manifested in the 1954 anti-comics screed Seduction of the Innocent. He is now known as one of the most iconic censors in modern history.

Wertham was a pioneering neurobiologist, and he worked extensively to fight stigmas associated with mental illness in children. He was an early advocate for poor and disenfranchised mentally ill individuals receiving fair criminal trials and for allowing their background and mental health serve in their defense. Wertham was progressive on many social issues, including helping establishing the Lafargue Clinic in Harlem, a low-cost non-discriminatory psychiatric center. Further, he was the author of important studies that concluded racial segregation was detrimental to children’s mental health, and he was instrumental in Brown v. Board of Education, helping eliminate the racial segregation of children in public schools.

However, it was during his work at the Lafargue Clinic that Wertham began to make questionable connections between juvenile delinquency and the popularity of comics.

Wertham’s opening salvo against comics came in an article published in Ladies Home Journal called, “What Parents Don’t Know about Comic Books.” He went on to publish his notorious book Seduction of the Innocent, which became a national sensation, wreaking havoc on the comics industry for years to come.

Wertham’s opening salvo against comics came in an article published in Ladies Home Journal called, “What Parents Don’t Know about Comic Books.” He went on to publish his notorious book Seduction of the Innocent, which became a national sensation, wreaking havoc on the comics industry for years to come.

Seduction of the Innocent was a work of junk science that vilified horror, crime, jungle and superhero comics. Wertham asserted that comics were a corrupting influence on youth and a leading cause of juvenile delinquency. Wertham’s “science” was based around the habits of at-risk youth, lacked a control group, and did not account for the habits of adult comic readers. Chock full of specious claims and unscientific conclusions, Seduction remains infamous for the assertions that Batman and Robin were involved romantically, Superman was an anti-American fascist, and most egregiously, the conclusion that crime comics were teaching children how to commit violent and evil acts.

Wertham’s assertions against the medium prompted brutal censorship and lasting stigma against comics.

Comics on Trial

In response to the public outcry raised by Wertham in popular magazines and Seduction of the Innocent, comics were put on trial by the United States government in 1954 by the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency. For two days in April 1954 senators heard testimony from child psychologists, comic book publishers, and cartoonists seeking insight into whether comics required government regulation.

The first day’s afternoon session was decisive in leading to widespread censorship of comics. Dr. Wertham was the first on the stand, repeating his well-rehearsed assertions that comics were a direct cause of juvenile delinquency. He said:

I would like to point out to you one other crime comic book which we have found to be particularly injurious to the ethical development of children and those are the Superman comic books. They arose in children phantasies of sadistic joy in seeing other people punished over and over again while you yourself remain immune. We have called it the Superman complex.

In these comic books the crime is always real and the Superman’s triumph over good is unreal. Moreover, these books like any other, teach complete contempt of the police. For instance, they show you pictures where some preacher takes two policemen and bang their heads together or to quote from all these comic books you know, you can call a policeman cop and he won’t mind, but if you call him copper that is a derogatory term and these boys we teach them to call policemen coppers.

All this to my mind has an effect, but it has a further effect and that was very well expressed by one of my research associates who was a teacher and studied the subject and she said, “Formerly the child wanted to be like daddy or mommy. Now they skip you, they bypass you. They want to be like Superman, not like the hard working, prosaic father and mother.”

Talking further about the ethical effects of comic books, you can read and see over and over again the remark that in crime comic books good wins over evil, that law and order always prevails. We have been astonished to find that this remark is repeated and repeated, not only by the comic books industry itself, but by educators, columnists, critics, doctors, clergymen. Many of them believe it is so.

Mr. Chairman, it is not. In many comic books the whole point is – that evil triumphs; that you can commit a perfect crime. I can give you so many examples that I would take all your time.

I will give you only one or two. Here is a little 10-year-old girl who killed her father, brought it about that her mother was electrocuted. She winks at you because she is triumphant. I have stories where a man spies on his wife and in the last picture you see him when he pours the poison in the sink, very proud because he succeeded. There are stories where the police captain kills his wife and has an innocent man tortured into confessing in a police station and again is triumphant in the end.

I want to make it particularly clear that there are whole comic books in which every single story ends with the triumph of evil, with a perfect crime unpunished and actually glorified.

In connection with the ethical confusion that these crime comic books cause, I would like to show you this picture which has the comic book philosophy in the slogan at the beginning, “Friendship is for Suckers! Loyalty ─ that is for Jerks.”

Wertham continued:

The second avenue along which comic books contribute to delinquency is by teaching the technique and by the advertisements for weapons. If it were my task, Mr. Chairman, to teach children delinquency, to tell them how to rape and seduce girls, how to hurt people, how to break into stores, how to cheat, how to forge, how to do any known crime, if it were my task to teach that, I would have to enlist the crime comic book industry.

Formerly to impair the morals was a minor was a punishable offense. It has now become a mass industry. I will say that every crime of delinquency is described in detail and that if you teach somebody the technique of something you, of course, seduce him into it.

Nobody would believe that you teach a boy homosexuality without introducing him to it. The same thing with crime.

For instance, I had no idea how one would go about stealing from a locker in Grand Central, but I have comic books which describe that in minute detail and I could go out now and do it.

Now, children who read that, it is just human, are, of course, tempted to do it and they have done it. You see, there is an interaction between the stories and the advertisements. Many, many comic books have advertisements of all kinds of weapons, really dangerous ones, like .22 caliber rifles or throwing knives, throwing daggers; and if a boy, for instance, in a comic book sees a girl like this being whipped and the man who does it looks very satisfied and on the last page there is an advertisement of a whip with a hard handle, surely the maximum of temptation is given to this boy, at least to have fantasies about these things.

It is my conviction that if these comic books go to as many millions of children as they go to, that among all these people who have these fantasies, there are some of them who carry that out in action.

Wertham concluded:

Mr. Chairman, I am just a doctor. I can’t tell what the remedy is. I can only say that in my opinion this is a public-health problem. I think it ought to be possible to determine once and for all what is in these comic books and I think it ought to be possible to keep the children under 15 from seeing them displayed to them and preventing these being sold directly to children.

In other words, I think something should be done to see that the children can’t get them. You see, if a father wants to go to a store and says, “I have a little boy of seven. He doesn’t know how to rape a girl; he doesn’t know how to rob a store. Please sell me one of the comic books,” let the man sell him one, but I don’t think the boy should be able to go see this rape on the cover and buy the comic book. I think from the public-health point of view something might be done now, Mr. Chairman …

Before Wertham was released from the stand, senators called attention to a satirical propaganda piece published in EC’s Haunt of Fear entitled “Are You A Red Dupe?” giving Wertham the opportunity to address the “smear” against him.

Wertham dismissed the piece. “This is from comic books. I have really paid no attention to this,” he said. But the senators had, and they were about to call its publisher as its next witness.

Wertham dismissed the piece. “This is from comic books. I have really paid no attention to this,” he said. But the senators had, and they were about to call its publisher as its next witness.

William Gaines & EC Comics

Bill Gaines was the son of Max Gaines, who, as the originator of the four-color, saddle stitch newspaper pamphlet, was one of the most influential men in the creation of comics. Bill Gaines inherited the publishing house “Educational Comics” after his father died in a freak boating accident. Gaines renamed the company “Entertaining Comics” and proceeded to make some of the greatest comics of the 20th Century.

The comics published by EC between 1949 and 1954 are still held as brilliant examples of illustrated storytelling. Gaines enlisted some of the finest illustrators in the field’s history to breathe life into stories that could stand shoulder to shoulder with popular film and radio stories within the science fiction, horror, crime and war genres. He was also notable for establishing the satirical comic series Mad under the editorial stewardship of Harvey Kurtzman.

Crashed and Burned

William Gaines was 32 years old and filled with righteous indignation and undergoing amphetamine withdrawal when he voluntarily took the stand before the Senate Subcommittee.

According to Amy Kiste Nyberg in Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code:

Gaines originally had been scheduled to appear in the morning, but other witnesses apparently ran on longer than expected, pushing Gaines’ testimony until after lunch. After the committee reconvened, however, Wertham appeared to testify, and the committee moved him ahead of Gaines. Gaines later contended that the postponement of his appearance adversely affected his testimony. According to his biographer, Gaines was taking diet pills, and as the medication began to wear off, fatigue set in. Gaines recalled: “At the beginning, I felt I was really going to fix those bastards, but as time went on I could feel myself fading away… They were pelting me with questions and I couldn’t locate the answers.”

The young publisher unwisely chose to testify of his own volition and had the poor fortune to approach the stand with flagging energy to face the hostile interrogation of senators, who had just respectfully heard Wertham’s indictment of comics and who were rankled by his “Red Dupe” cartoon. Although the cards were stacked against him, Gaines took the stand with an air of defiance. In the first moments of his testimony he declared, “I was the first publisher in these United States to publish horror comics. I am responsible, I started them. Some may not like them. That is a matter of personal taste. It would be just as difficult to explain the harmless thrill of a horror story to a Dr. Wertham as it would be to explain the sublimity of love to a frigid old maid.”

Gaines’ remarks then grew more confrontational:

Entertaining reading has never harmed anyone. Men of good will, free men should be very grateful for one sentence in the statement made by Federal Judge John M. Woolsey when he lifted the ban on Ulysses. Judge Woolsey said, “It is only with the normal person that the law is concerned.” May I repeat, he said, “It is only with the normal person that the law is concerned.” Our American children are for the most part normal children. They are bright children, but those who want to prohibit comic magazines seem to see dirty, sneaky, perverted monsters who use the comics as a blueprint for action. Perverted little monsters are few and far between. They don’t read comics. The chances are most of them are in schools for retarded children.

What are we afraid of? Are we afraid of our own children? Do we forget that they are citizens, too, and entitled to select what to read or do? Do we think our children are so evil, so simple minded, that it takes a story of murder to set them to murder, a story of robbery to set them to robbery? Jimmy Walker once remarked that he never knew a girl to be ruined by a book. Nobody has ever been ruined by a comic.

As has already been pointed out by previous testimony, a little healthy, normal child has never been made worse for reading comic magazines. The basic personality of a child is established before he reaches the age of comic-book reading. I don’t believe anything that has ever been written can make a child overaggressive or delinquent. The roots of such characteristics are much deeper. The truth is that delinquency is the product of real environment, in which the child lives and not of the fiction he reads.

There are many problems that reach our children today. They are tied up with insecurity. No pill can cure them. No law will legislate them out of being. The problems are economic and social and they are complex. Our people need understanding; they need to have affection, decent homes, decent food. Do the comics encourage delinquency? Dr. David Abrahamsen has written: “Comic books do not lead into crime, although they have been widely blamed for it. I find comic books many times helpful for children in that through them they can get rid of many of their aggressions and harmful fantasies. I can never remember having seen one boy or girl who has committed a crime or who became neurotic or psychotic because he or she read comic books.”

Gaines’ defiant stance flew against the public mood, and his own inexperience opened a line of testimony that was a publicity disaster and sealed the industry’s fate, seen in this infamous exchange:

Chief Counsel Herbert Beaser: Let me get the limits as far as what you put into your magazine. Is the sole test of what you would put into your magazine whether it sells? Is there any limit you can think of that you would not put in a magazine because you thought a child should not see or read about it?

Bill Gaines: No, I wouldn’t say that there is any limit for the reason you outlined. My only limits are the bounds of good taste, what I consider good taste.

Beaser: Then you think a child cannot in any way, in any way, shape, or manner, be hurt by anythin

g that a child reads or sees?

Gaines: I don’t believe so.

Beaser: There would be no limit actually to what you put in the magazines?

Gaines: Only within the bounds of good taste.

Beaser: Your own good taste and saleability?

Gaines: Yes.

Senator Estes Kefauver: Here is your May 22 issue. [Kefauver is mistakenly referring to Crime Suspenstories #22, cover date May.] This seems to be a man with a bloody axe holding a woman’s head up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?

Gaines: Yes sir, I do, for the cover of a horror comic. A cover in bad taste, for example, might be defined as holding the head a little higher so that the neck could be seen dripping blood from it, and moving the body over a little further so that the neck of the body could be seen to be bloody.

Kefauver: You have blood coming out of her mouth.

Gaines: A little.

Kefauver: Here is blood on the axe. I think most adults are shocked by that.

This exchange made the front pages of the next morning’s newspapers, most notably The New York Times, who ran the headline, “NO HARM IN HORROR, COMICS ISSUER SAYS.”

Code of Silence

Faced with an angry public and the threat of regulation by the government or self-regulation, the comics industry was backed into a corner. They responded by establishing the Comic Magazine Association of America, which instituted the Comics Code Authority, a censorship code that thoroughly sanitized the content of comics for years to come.

Faced with an angry public and the threat of regulation by the government or self-regulation, the comics industry was backed into a corner. They responded by establishing the Comic Magazine Association of America, which instituted the Comics Code Authority, a censorship code that thoroughly sanitized the content of comics for years to come.

Almost overnight, comics were brought down to a level appropriate only for the youngest or dimmest of readers. Horror, Crime, Science Fiction and other genres appealing to older and more sophisticated readers were wiped out for a generation.

Here’s a sampling of content banned by the Comics Code:

Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal, to promote distrust of the forces of law and justice, or to inspire others with a desire to imitate criminals.

If crime is depicted it shall be as a sordid and unpleasant activity.

Policemen, judges, government officials, and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.

Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates a desire for emulation.

In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

Scenes of excessive violence shall be prohibited. Scenes of brutal torture, excessive and unnecessary knife and gunplay, physical agony, gory and gruesome crime shall be eliminated.

No comic magazine shall use the word horror or terror in its title.

All scenes of horror, excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust, sadism, masochism shall not be permitted.

All lurid, unsavory, gruesome illustrations shall be eliminated.

Inclusion of stories dealing with evil shall be used or shall be published only where the intent is to illustrate a moral issue and in no case shall evil be presented alluringly, nor so as to injure the sensibilities of the reader.

Scenes dealing with, or instruments associated with walking dead, torture, vampires and vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism are prohibited.

Profanity, obscenity, smut, vulgarity, or words or symbols which have acquired undesirable meanings are forbidden.

Nudity in any form is prohibited, as is indecent or undue exposure.

Suggestive and salacious illustration or suggestive posture is unacceptable.

Females shall be drawn realistically without exaggeration of any physical qualities.

Illicit sex relations are neither to be hinted at nor portrayed. Rape scenes as well as sexual abnormalities are unacceptable.

Seduction and rape shall never be shown or suggested.

Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden.

Nudity with meretricious purpose and salacious postures shall not be permitted in the advertising of any product; clothed figures shall never be presented in such a way as to be offensive or contrary to good taste or morals.

The Code’s Impact

CBLDF columnist Joe Sergi writes:

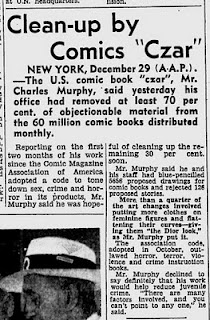

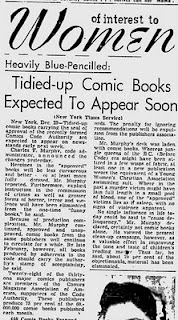

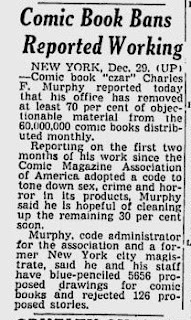

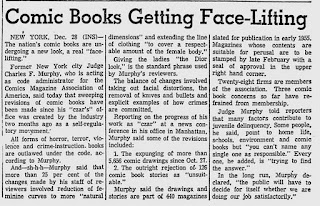

Although the Comics Code Authority had no official control over publishers, most distributors refused to carry comics that did not carry the seal. On December 24, 1954, The New York Times reported “NEW COMIC BOOKS TO BE OUT IN WEEK; First ‘Approved’ Issues Put More Clothing on Heroines and Tone Down Violence” by Dorothy Barcla. Soon, other stories appeared around the country and even in other parts of the world were talking about it. Here are some samples:

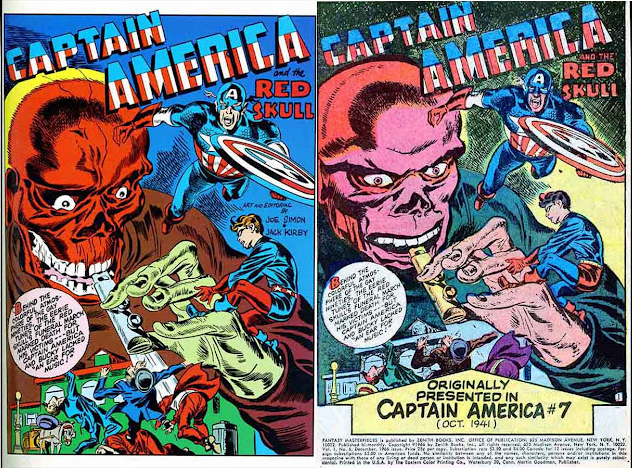

Sergi’s research also spotlights how the Code altered the work of comics master Jack Kirby to illustrate how the standards affected the way stories were told:

This splash page was changed presumably because it was too scary. The bound woman is also removed. The original is from Captain America #6 and it was reprinted in Fantasy Masterpiece#6.

The same issue also featured a Red Skull story from Captain America #7. You will note that he looks less frightful and more like a man in a mask. Apparently, that was something the people at the Comics Code insisted on.

Fallout

The impression that the Senate hearings left on the public and the subsequent censorship of the Code decimated the comics industry. Creators who’d made their careers writing or illustrating comics now lied about their profession in polite company because admitting to working in comics was viewed as a calling so deviant that it was aligned with being a fringe pornographer.

According to David Hajdu in The 10-Cent Plague, the work for cartoonists dried up, with the number of titles published dropping from 650 titles in 1954 to 250 in 1956. The consequence was that more than 800 working creators lost their jobs. The commercial rejection of comics and the business altering restrictions of the Code were still not enough for some critics. Hajdu writes: “More than a hundred acts of legislation were introduced on the state and municipal levels to ban or limit the sale of comics: Scores of titles were outlawed in New York, Connecticut, Maryland, and other states, and ordinances to regulate comics were passed in dozens of cities.”

Among the most egregious censorship bills was a New York law that served to:

- prohibit the publication or the distribution of lurid comics, defined as those ‘devoted to or principally made up of pictures or accounts of methods of crime, or illicit sex, horror, terror, physical torture, brutality, or physical violence’

- bar the sale of any such books to those under the age of 18

- ban the use of the words ‘crime,’ ‘terror,’ ‘horror,’ or ‘sex’ in comic book titles.

Violations were punishable by one year in jail, a $500 fine, or both. The law was passed by the legislature on March 22, 1955, and signed into law on May 2, 1955.

According to Hajdu, by fall of 1955, bills on comic books had passed in the legislative bodies of California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, and Washington. Legislation was proposed and either voted down or not acted upon in Delaware, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, New Mexico, South Dakota, Utah, and Wisconsin.

The Senate Subcommittee hearings, the Comics Code, and the subsequent flurry of laws regulating the sale of comics combined to form the most brutal era of censorship arising from moral panic that American pop culture has ever known.