by Joe Sergi

A little note before I begin. The below discussion involves a little more legal theory and history than I am usually comfortable writing about. And while I am a lawyer, I do not practice First Amendment Law. And while a card carrying member of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF) and I regularly contribute to them, I have never worked for or represented the CBLDF (and am actually restricted from doing so by Federal Regulation). Most importantly, I did NOT stay in a Holiday Inn Express last night. As a result, nothing below is meant to be legal advice or even a legal opinion. I’m merely summarizing what happened at the panel (and giving my personal views as a creator and following up where applicable). In short, “Some restrictions apply”; “void where prohibited by law and not available in NJ”; and “Do not taunt happy fun ball.” Now that that’s out of the way (darn lawyers):

I attended a great presentation by Charles Brownstein, the Executive Director of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF), which traced the history of censorship in America. Surprisingly, C2E2 actually had two panels on censorship and scheduled them at exactly the same time. To their credit, once the organizers realized this, they moved the CBLDF Panel. The other one was done by the ALA and I didn’t get to attend. But, I made it a point to attend the CBLDF panel (and gave up a chance to hang with John Cusack to do it—sorry John). It was called “CBLDF: The History (and Future) of Comics Censorship.”

I attended a great presentation by Charles Brownstein, the Executive Director of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF), which traced the history of censorship in America. Surprisingly, C2E2 actually had two panels on censorship and scheduled them at exactly the same time. To their credit, once the organizers realized this, they moved the CBLDF Panel. The other one was done by the ALA and I didn’t get to attend. But, I made it a point to attend the CBLDF panel (and gave up a chance to hang with John Cusack to do it—sorry John). It was called “CBLDF: The History (and Future) of Comics Censorship.”

I am a big fan of the CBLDF and the work they do. I wrote a post about them here. A relative young organization, only in existence for 26 year, the CBLDF exists to protect the First Amendment Rights of creators, retailer, and libraries. And why many people know what they do, this panel highlighted the reasons why we need a CBLDF in the world. I took fairly comprehensive notes and will do my best at summarizing Mr. Brownstein’s fascinating lecture.

Brownstein started by reading the First Amendment and stressing the importance of the exact words. I agree with him and so I will reproduce them here in full:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

If you look at those words, the First Amendment doesn’t say that only free speech that you are comfortable with or agree with is protected; it says that all free speech is protected. Obscenity, on the other hand, is not protected. And throughout history kids try to rebel and parents try to protect them by reining them in. That is a noble goal, but sometimes people freak out and overcompensate. And when things are taken too far, you end with censorship. Sadly, censorship arising from moral panic is a constant presence in the history of comics. From the thirties to the modern day, the medium has been stigmatized as warping young minds.

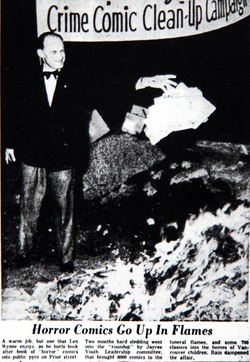

Comics came out in the 30s and pretty much from that day moral crusaders said that comics corrupted youth. This outcry led to a rash of public criticism in popular magazines and newspapers. In fact, it got so bad that people actually led to comic book burning.

Comics came out in the 30s and pretty much from that day moral crusaders said that comics corrupted youth. This outcry led to a rash of public criticism in popular magazines and newspapers. In fact, it got so bad that people actually led to comic book burning.

Brownstein pointed out the absurdity of this as comics were powerfully important in influencing society and the youth. In fact, he gave the statistic that during World War II, 25% of printed matter sent to military wee comics. And while these comics were fine for the young men and women defending the country, those same books were being burned back in the states.

In response the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers was created in 1948 to regulate the industry and create rules which were modeled loosely after the 1930 Hollywood Production Code. Essentially, this code banned graphic depictions of violence and gore in crime and horror comics, as well as the sexual innuendo of what aficionados refer to as good girl art. But, the organization never took off.

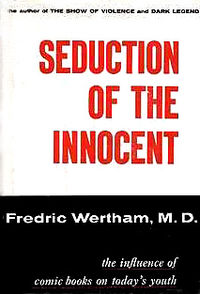

Dr. Fredrick Wertham

Dr. Fredrick Wertham

I’m not sure there is a comic book fan who isn’t familiar with the infamous Dr. Wertham or his book, Seduction of the Innocent.

Dr. Wertham was a child psychologist who worked with juvenile delinquents. Juvenile delinquency was on the rise in America in the 1950s and he tried to figure out why. He discovered that many of his patients read comics. As a result, he concluded that comics were a corruptive influence on children. Apparently, he was also a media hound who was always looking for way to be in the spotlight and his used his anti-comics soap box as a road to celebrity.

The apex of his anti-comics work was the 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent, which vilified horror, crime, and superhero comics. This book led to the brutal censorship of comics in the 1950s. Brownstein again showed the hypocrisy of Wertham’s position by pointing out the Werthams’s view of child sidekicks as homoerotic child abuse, when in fact the sidekick was created as a way to help kids deal with their absentee father figures who were shipped overseas during the war.

As a result of Wertham’s crusade, the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency held hearings in 1954. Wertham was asked to testify to a room of sympathetic Senators. He made a convincing case.

On the same day, Congress also heard from William Gaines, the publisher of EC Comics. EC comics printed crime and horror comics (Brownstein didn’t mention it, but I always found it kind of ironic that EC Comics started by printing Bible comics.) EC Comics, which included titles such as Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, Shock SuspenStories, Weird Science and Two-Fisted Tales, featured stories with content above the level of the typical comic. For some reason, Gaines volunteered to appear at the hearing (which is never good advice). He also was on diet pills. So, by the time he actually was able to testify after Wertham, he was crashing on the pills and experiencing flop sweats. To make matters worse, he was defiant in his testimony and met with disdain from the Senators. In short, his testimony was a public disaster and led to further public backlash against comics.

To bring the story home, Brownstein mentioned a few examples, such as the aggressive opening remarks by Gaines. I was able to track down a copy of them, he said:

- “Entertaining reading has never harmed anyone. Men of good will, free men should be very grateful for one sentence in the statement made by Federal Judge John M. Woolsey when he lifted the ban on Ulysses. Judge Woolsey said, ‘It is only with the normal person that the law is concerned.’ May I repeat, he said, “It is only with the normal person that the law is concerned.” Our American children are for the most part normal children. They are bright children, but those who want to prohibit comic magazines seem to see dirty, sneaky, perverted monsters who use the comics as a blueprint for action. Perverted little monsters are few and far between. They don’t read comics. The chances are most of them are in schools for retarded children. What are we afraid of? Are we afraid of our own children? Do we forget that they are citizens, too, and entitled to select what to read or do? Do we think our children are so evil, so simple minded, that it takes a story of murder to set them to murder, a story of robbery to set them to robbery? Jimmy Walker once remarked that he never knew a girl to be ruined by a book. Nobody has ever been ruined by a comic.”

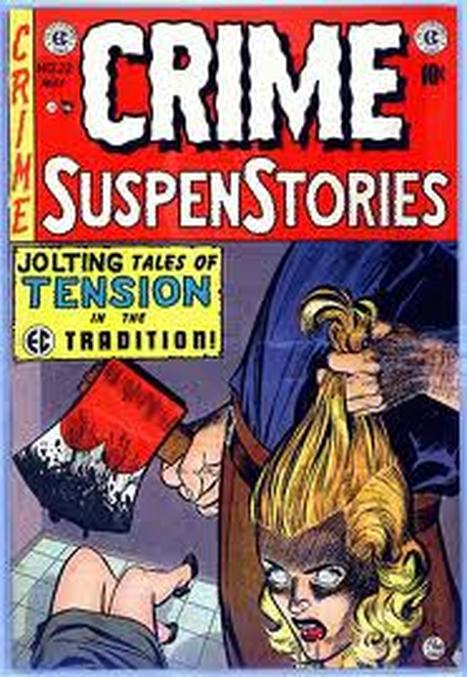

Brownstein also mentioned that, during the hearing Gaines was showed a cover of Crime Suspense Stories, which featured a killer carrying the severed head of a woman and an axe and was asked whether he thought it was in good taste. As a result of his responses, the major newspapers announced in headlines that “Crime publisher says shock comics in good taste.”

If you are curious, here is a copy of that infamous cover.

And a copy of his testimony:

- Chief Counsel Herbert Beaser: Let me get the limits as far as what you put into your magazine. Is the sole test of what you would put into your magazine whether it sells? Is there any limit you can think of that you would not put in a magazine because you thought a child should not see or read about it?

- Bill Gaines: No, I wouldn’t say that there is any limit for the reason you outlined. My only limits are the bounds of good taste, what I consider good taste.

- Beaser: Then you think a child cannot in any way, in any way, shape, or manner, be hurt by anything that a child reads or sees?

- Gaines: I don’t believe so.

- Beaser: There would be no limit actually to what you put in the magazines?

- Gaines: Only within the bounds of good taste.

- Beaser: Your own good taste and saleability?

- Gaines: Yes.

- Senator Estes Kefauver: Here is your May 22 issue. [Kefauver is mistakenly referring to Crime Suspenstories #22, cover date May] This seems to be a man with a bloody axe holding a woman’s head up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?

- Gaines: Yes sir, I do, for the cover of a horror comic. A cover in bad taste, for example, might be defined as holding the head a little higher so that the neck could be seen dripping blood from it, and moving the body over a little further so that the neck of the body could be seen to be bloody.

- Kefauver: You have blood coming out of her mouth.

- Gaines: A little.

- Kefauver: Here is blood on the axe. I think most adults are shocked by that.

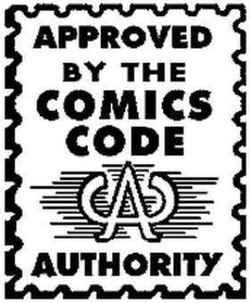

Code of Silence

Code of Silence

After the devastating Senate hearings, the comics industry was faced with an angry public and the fear of Congressional interference through adverse regulations. In response, the industry created the Comics Code Authority (CCA). Similar to the Association of Comic Magazine Publishers, the CCA sought self-regulate comics. Essentially, the CCA sought to sanitize comics and eliminated the crime and horror genres. Essentially, comics for older teens and adult disappeared for nearly fifteen years.

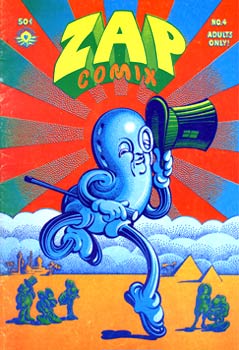

The Underground Comix Movement

The Underground Comix Movement

From 1966 through 1973, there a movement called underground comix. Underground comix emerged as an uncensored form of art that challenged class, sexuality, equality, politics, and drugs. (I should add that I don’t particularly enjoy reading underground comix and they are not my cup of tea. But, that is a far cry for believing that they should be pulled off the market.) Underground comix thrived for less than ten years because of changes in the law. These changes came about with a criminal case involving Zap Comix. Although Zap Comix was thought to be the gold standard for underground commix, it was also the first to be found to be legally obscene.

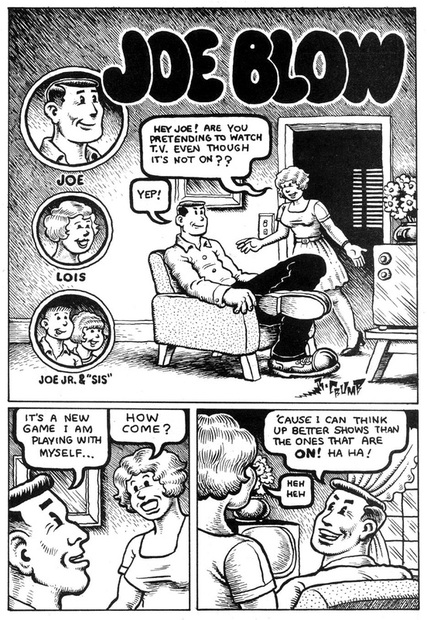

Specifically, there was a story in Zap Comix #4 that attacked social conventions. One of the stories, “Joe Blow” by Robert Crumb, was drawn in a simple line Walt Disney style and featured a white collared executive who, after a hard day at the office, enjoyed spending quality time with his nuclear family. Of course, this quality time consisted of an incestual orgy (with the motto “the family that lays together, stays together.”), thus providing a unique commentary on the hypocrisy of America. Brownstein added that Crumb is now hanging in several museums. Zap Comix #4 was the subject of a sting operation and retailers who offered it were prosecuted for (and found guilty of) selling obscenity in New York. The book was also prohibited from being sold over the counter in New York. It is interesting to note that Judge Joel Tyler, who provided over the case is the same judge who made Deep Throat famous by ruling it to be obscene. In the Zap Comix opinion, Judge Tyler stated, “. . . the cartoon is ugly, cheap and degrading. Its purpose—to stimulate erotic responses, and does not, as claimed, deal with basic realities of life. It is grossly shocking—demeaning the sexual experience by perverting it . . . it is part of the underworld press—the growing world of deceit in sex, and it is not reality or honesty, as they often claim it to be. It represents an emotional incapacity to view sex as a basic part of the human condition.” After the panel, I did some research and discovered that when Judge Tyler retired, he said, referring to the Deep Throat decision, “If I were to write that appendix today, I would be deemed a fool, given the substantial change in our outlook.” Given the recognition of Crumb, Pekar, and many other underground creators , I think he would agree that the statement would equally apply to the Zap Comix decision. I found out Judge Tyler died in January at the age of 90.

Brownstein next discussed the 1973 decision in Miller v. California, in which the United States Supreme Court laid down the standard for constitutes unprotected obscenity for First Amendment purposes. (I’m not sure I mentioned it earlier, but it is clear that “obscenity” is not protected by the First Amendment.) Brownstein then articulated what has become known as the Miller test for determining what constituted obscene material. The test has three parts:

Brownstein next discussed the 1973 decision in Miller v. California, in which the United States Supreme Court laid down the standard for constitutes unprotected obscenity for First Amendment purposes. (I’m not sure I mentioned it earlier, but it is clear that “obscenity” is not protected by the First Amendment.) Brownstein then articulated what has become known as the Miller test for determining what constituted obscene material. The test has three parts:

- Whether “the average person, applying contemporary community standards”, would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest,

- Whether the work depicts/describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by applicable state law,

- Whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.

The work is considered obscene only if all three conditions are satisfied. (I should add that the first two prongs of the Miller test are held to the standards of the community, and the last prong is held to what is reasonable to a person of the United States as a whole.) Brownstein added that After the Miller decision, content businesses braced for combat and many shops simply removed questionable material from their sheleves. Basically, it was a fatal blow for Underground Comix.

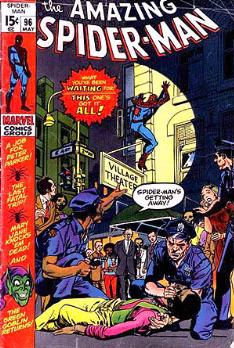

Spidey vs. Drugs

Spidey vs. Drugs

An interesting thing happened in the lates 60s/early 70s, while the underground was dying, mainstream comics were thriving. Brownstein discussed that in 1971, Stan Lee, at the request of the government, wrote a Spider-Man comic dealing with drug abuse. This comic violated the Comics Code and did not receive approval, but Marvel still released the book. The success of the issue and the importance of the issue led to the amendement of the code to allow drug use so long as it was depicted as a viscious habit.

Through some post panel research, I discovered that the book was requested by the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare. The three issue story ran from #96–98 (cover date of May–July 1971) . I should also mention that the Comics Code at the time did not specifically forbid depictions of drugs. Instead, Marvel ran afoul of the a clause prohibiting “All elements or techniques not specifically mentioned herein, but which are contrary to the spirit and intent of the code, and are considered violations of good taste or decency”. At the time, acting administrator John L. Goldwater, publisher of Archie Comics, refused to grant Code approval based on the depiction of narcotics being used, regardless of the context. For those of you really interested, I should add that I remember, from a previous panel that the CCA had previously approved a story involving drugs, in Strange Adventures #205 (Oct. 1967), in which Deadman fought opium smugglers. But I digress.

Fandom Carries the Torch

Fandom Carries the Torch

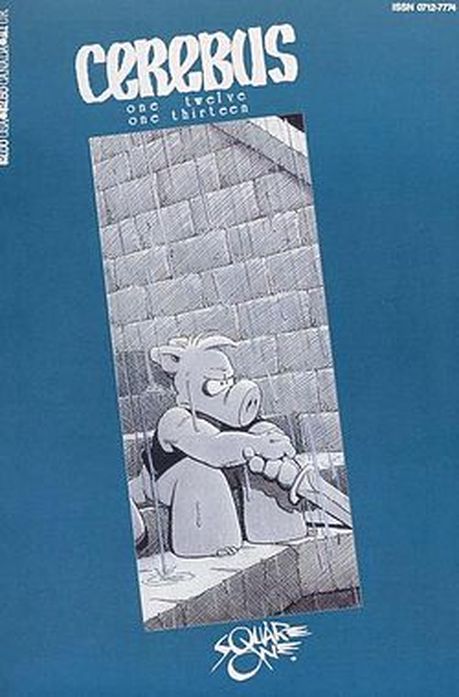

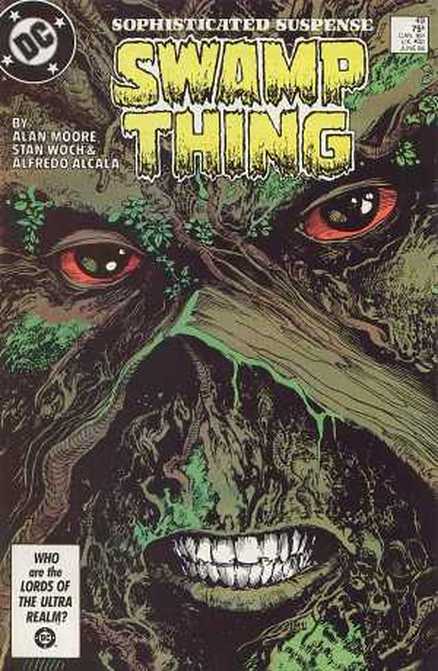

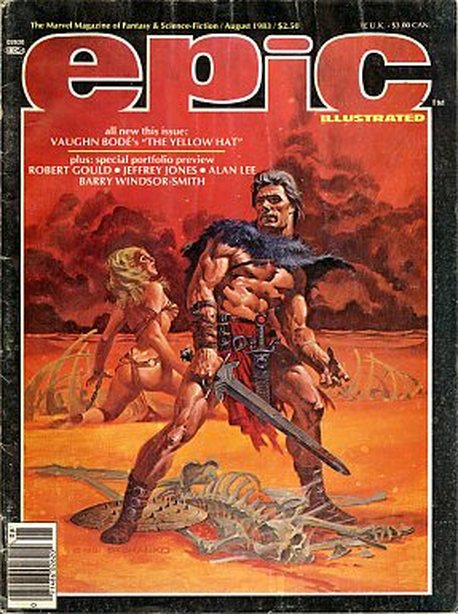

The panel next moved into how organized fandom saved comics through the use of conventions and specialty stores. These led to the creation of what has become known as the Direct Market and for bringing Japanese Manga to be introduced in America. As a result, the 1980s saw a huge surge of comics published for adults. Brownstein cited numerous examples of both independent books (like Fantographics, Cerebus, and Elfquest) and the experimentation done by Marvel and DC (like Epic Illustrated and Alan Moore’s run on Swamp Thing). However, the new comics revolution really started with the release of the Dark Knight Returns and Watchman, which put comics on the forefront as a means to offer commentary on society. Also at this time, Viz Media began to bring Manga to American audiences with more adult themes and simple line art. In short, comics (along with pop culture, in general) were being viewed as having artistic merit.

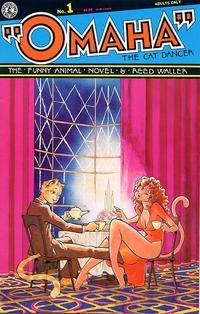

Of course, with the increased exposure and recognition of artistic merit came added exposure and, at times, overzealousness on the part of law enforcement authorities. On November 18, 1986, police officers had come into the shop, and seized seven comic titles, including Omaha the Cat Dancer, Weirdo and Heavy Metal. They also arrested the store manager, Michael Correa, on charges of displaying obscene material. Ultimately, Correa was fined $750.00 and sentenced to one year probation. Brownstein then commented that, after the long history of oppression, the comics industry wasn’t going to be beaten down again. So, Denis Kitchen got some money together, hired a lawyer named Burton Joseph who was a well-known attorney who specialized in First Amendment cases. Joseph got the Correa conviction overturned.

I found out after the panel that Kitchen felt a personal sense of responsibility because his company, Kitchen Sink Press published Omaha the Cat Dancer, one of books sold by Correa that resulted in his arrest. Kitchen then created limited edition prints (made by some of the biggest names in the industry) and raised around $20,000 (including his own personal contributions), which was put into a bank account for the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

I found out after the panel that Kitchen felt a personal sense of responsibility because his company, Kitchen Sink Press published Omaha the Cat Dancer, one of books sold by Correa that resulted in his arrest. Kitchen then created limited edition prints (made by some of the biggest names in the industry) and raised around $20,000 (including his own personal contributions), which was put into a bank account for the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

Brownstein stressed that he couldn’t discuss the work by the organization is done before a case is filed. So, most of the work done by the CBLDF is never seen. Brownstein did specifically mentioned some of the cases that the CBLDF assisted with:

Brownstein stressed that he couldn’t discuss the work by the organization is done before a case is filed. So, most of the work done by the CBLDF is never seen. Brownstein did specifically mentioned some of the cases that the CBLDF assisted with:

- Comic artist Paul Mavides prevailed against a resolution by the State of California to levy a sales tax on comic strips and comic books with assistance from the CBLDF

- Florida based underground comic book artist Mike Diana was convicted for obscenity stemming from his self-published Boiled Angel. The CBLDF was unable to overturn the conviction and Diana served his sentence in New York.

- Comic book artist Kieron Dwyer was sued by Starbucks Coffee and was forced to comply with an injunction saying could no longer use his logo for its confusing similarity to that of Starbucks.

- Although not mentioned in the panel, the CBLDF filed a friend-of-the-court brief (amicus Brief) in Schwarzenegger v. EMA, successfully urging the Supreme Court to affirm the Ninth Circuit’s decision that a California law banning the sale or rental of any video game containing violent content to minors, and requiring manufacturers to label such games, is unconstitutional. I attended to the oral argument.

Manga Under Attack

Manga Under Attack

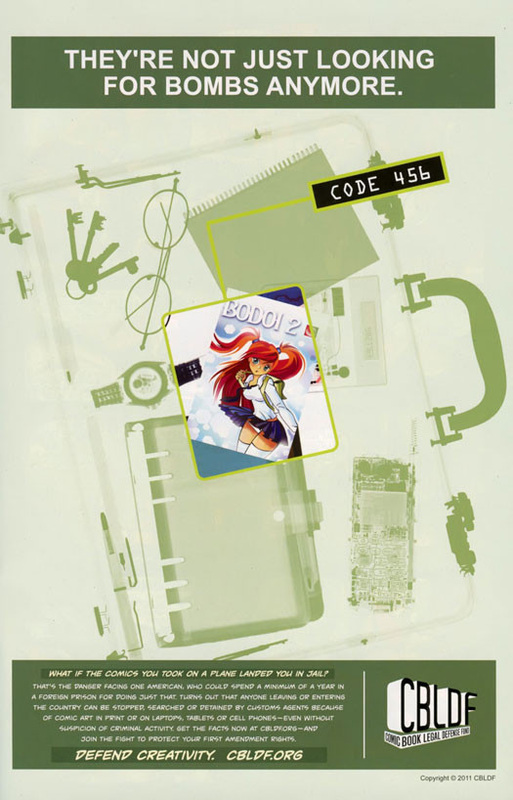

Brownstein then turned to the most recent case, involving Ryan Matheson, who was detained by Canadian authorities and accused of possessing and importing Child Pornography because they found two comic Manga images on his laptop. (This is also known as the Brandon X case). Brownstein showed one of the confiscated images, which was called the Shijūhatte (“the 48 positions”), which showed The Japanese drawings style that features super cutey childlike figures (I think it’s called “Moe”, but don’t quote me) having sex. They also confiscated a fan sketch that Brownstein said was like anything that was being sold in artist alley.

After a search of his laptop in 2010, Matheson was wrongfully accused of possessing and importing child pornography because of constitutionally protected comic book images on that device. He was subjected to abusive treatment by police and a disruption in his life that included a two-year period during which he was unable to use computers or the internet outside of his job, severely limiting opportunities to advance his employment and education. Thanks, in part to the work of the CBLDF, the Canadian Authorities have since withdrawn all charges against Matheson. But, then Brownstein stated that the CBLDF assisted in paying some of the legal bills (which exceeded $75,000) incurred by Matheson and provided expert support. CBLDF is currently seeking funds to help pay off the $45,000 debt Matheson incurred as a result of his case, and to create new tools to prevent future cases.

Brownstein heralded Matheson’s attitude of not backing down and being willing to fight for the art form that he loved.

And, while not mentioned on the panel, I should add that I had read somewhere that Comic artists Tom Neely and Dylan Williams also had books they were carrying over the US/Canadian border confiscated because the custom officials weren’t familiar with Manga. So if you are traveling you have to be careful. The CBLDF has written a Legal memorandum on Candaian issues available at https://cbldf.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/CBLDF-Legal-Memorandum-Canada-Issues.pdf and issued an advisory entitled, “CBLDF Advisory – Comic Book Art at Intl Borders” available at https://cbldf.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/CBLDF-Advisory-Comic-Book-Art-at-Intl-Borders.pdf. You should check them out if you have any concerns.

Final Statements

Final Statements

The prepared portion of the panel ended with what could be done. The most obvious easiest way to help would be to go make a contribution at www.cbldf.org. People should also spread the word about the CBLDF and cases like the one involving Matheson. People should take the time to learn about their rights and the CBLDF is a great place to start. Finally, if you have an interest you should consider writing an article for the site. Brownstein stressed that the CBLDF is a small organization that has received less than $500,000 in donation and has two people running it. They are lean and committed to the notion that comics are not a crime and no one should go to jail because of art.

I talked to Mr. Brownstein after the panel and found out that the CBLDF has acquired from the defunct CMAA the intellectual property rights to the Comics Code seal, which will not be used in their promotion.

I wish I could do more for this great organization.

Joe lives outside of Washington, DC with his wife, Yee, and daughter, Elizabeth. Joe has published short stories in the science fiction and horror genres. In addition, Joe has published several comic stories. Finally, Joe was selected as a semi-finalist in the Who Wants To Create A Superheroine contest sponsored by the Shadowline Imprint of Image Comics. In 2010, Joe was the awared the HALLER for Best Writer by the ComicBook Artist Guild at the 2010 New York ComicCon. Visit his website, Cup of Geek, here.

To bring this presentation to your school, convention, or event, please contact Charles.Brownstein@cbldf.org