by Joe Sergi

I was recently asked to join a Facebook Group called, “Comic Book Fans vs. a Bunch of Moms with Nothing Else Better To Do . . . ” This Group was created in response to the recent actions by the One Million Moms organization who are requesting that its supporters email Marvel and DC comic book companies, “…urging them to change and cancel all plans of homosexual superhero characters immediately. Ask them to do the right thing and reverse their decision to have sexual orientation displayed to readers.” Apparently, One Million Moms believes that if children read about gay characters, they will become gay. Marvel and Archie have responded, defending their positions, and several Social Media groups have begun to form on both sides of the issue. The last news I have heard is that the One Million Moms deleted their anti-gay Facebook page.

This kind of tension has always existed. On the one side, you have the welfare and protection of the community (especially children, who can’t protect themselves). On the other, you have fundamental liberties such as free speech. The problem is that the well intentioned actions of groups in the first category tend to infringe on the rights of the second because it is the simplest solution. This happened in the 1940s when civic minded parents decided that it was in the best interest of their children and the community to burn comic books, which leads me to my first “official” CBLDF column topic: book burning.

The first recorded state-sponsored book burning occurred in China in 213 BC at the direction of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, who also created the Great Wall and the Terracotta army. So, book burning has been around a long time. Motivations have ranged from religious persecutions to political statements. Throughout history, governments, church leaders, and librarians have taken part in burning, the most extreme of censorship methods. The Nazis used it in World War II to all but destroy books which did not correspond to their ideology. The Nazis were stopped in 1945. But, three short years later, book burners were back, and this time they came for the comics.

The first recorded state-sponsored book burning occurred in China in 213 BC at the direction of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, who also created the Great Wall and the Terracotta army. So, book burning has been around a long time. Motivations have ranged from religious persecutions to political statements. Throughout history, governments, church leaders, and librarians have taken part in burning, the most extreme of censorship methods. The Nazis used it in World War II to all but destroy books which did not correspond to their ideology. The Nazis were stopped in 1945. But, three short years later, book burners were back, and this time they came for the comics.

The year was 1948 and change was in the air. World War II was over, but the Cold War was just beginning. President Truman manages to sign the Marshall Plan into law, which authorizes $5 Billion in aid for 16 countries, and he beats both Thomas Dewey and Strom Thurman to stay in office. The United Nations forms the World Health Organization and adopts the Declaration of Human Rights. Columbia introduces the 33 1/3 record (ask your parents). Scientists publish a new paper announcing something called “The Big Bang Theory.” Olivier’s Hamlet and The Music Man are top box office earners and are shown along with the first color news reels. Cole Porter’s Kiss Me Kate opens on Broadway, and Nat King Cole was crooning on the radio. While all of this progress and growth was happening in the world, well intentioned parents and citizens were convincing their children to burn all their comic books in the United States.

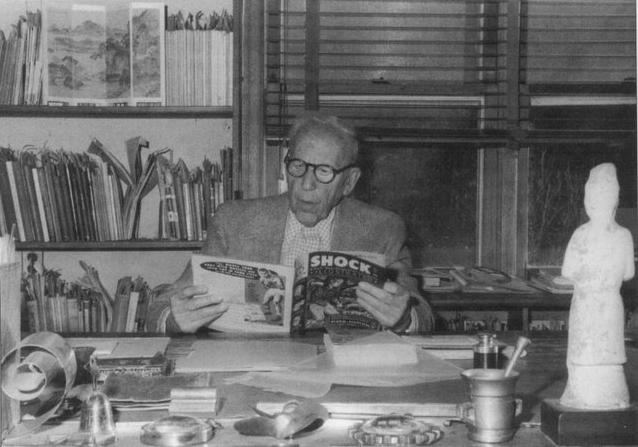

The Allied Forces had defeated Hitler three years earlier, and apparently people were looking for a new enemy. Dr. Fredric Wertham gave them one. As most people know, Wertham, a German-born psychiatrist, worked in a charitable hospital in Harlem treating juvenile delinquents. He discovered that many of these delinquents read comic books. Thus, Wertham concluded, comic books inspired children to become criminals. I assume that most of these children also wore shoes, so he could have just have easily concluded that footwear was the downfall of America, but he limited his studies to comics.

In 1948, Wertham began his public attack on comics with an interview in Collier’s Magazine called “Horror in the Nursery.” A short time later, he presented at a symposium entitled “The Psychopathy of Comic Books.” In May 1948, those same views were released, with the same name, in the American Journal of Psychotherapy and in the Saturday Review of Literature in an article entitled “The Comics . . . Very Funny” (excerpts would later be included in the August issue of Reader’s Digest). Wertham considered comic book readers to be “abnormally sexually aggressive” and thought that reading comics led to crime. Now, Wertham wasn’t the first person to have this opinion. But the problem was that Wertham was a highly distinguished psychologist who thought comic books were bad for kids and eloquently voiced his concerns. In fact, Wertham would later say to the 1954 U.S. Senate Subcommittee Hearing on Juvenile Delinquency, “I think Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry.” With Wertham pointing the finger and leading the charge, America had found a new enemy.

In response, several communities began to pass laws and put pressures on booksellers in order to stem the tide of the juvenile corruption caused by the four color menace known as the comic book. Things came to a head on October 26, 1948, in a small West Virginia town named Spencer, where children — overseen by priests, teachers, and parents — publicly burned several hundred comic books. For nearly a month, students gathered books. Then, they piled the books up into six foot high stack in the yard of the school. Then, six hundred children surrounded the comics and a student lit the cover of a Superman comic and threw it on top of the pile.

David Hajdu’s great book, The Ten Cent Plague has the following description of the Spencer burning:

The flames rose to a height of more than twenty-five feet as the children, their teachers, the principal, and a couple of reporters and photographers from the area papers watched for more than an hour….

When the Associated Press picked up the story from local accounts, readers of The Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune, and dozens of other papers around the country learned how, just three years after the second World War, American citizens were burning books.

Shortly after the Spencer Burning, residents of Binghamton, New York conducted a house to house collection of comic books and had a mass public comic book burning.

Gerard Jones, in his informative book, Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters and the Birth of the Comic Book described the event as follows.

An impromptu crusade in Binghamton, New York, sent volunteers door-to-door to ask, “Are there any comic books in this house?” When the households could be persuaded that doctors, police, and ministers were right about the dangers of comics, the volunteers gathered the offending publications and carried them to the local school yard, where they were piled high, doused with gasoline, and set afire. Time ran pictures of the comics blazing, children watching with some ambivalence from the background.

The following picture of the Binghamton Burning was featured in the December 20th issue of Time.

The caption under the picture read,

Manners and Morals

In Binghamton, N.Y., Students of St. Patrick’s parochial school collected 2,000 objectionable comic books in a house-to-house canvass, burned them in the school yard.

As a result of this coverage, similar events followed in many other cities. In Rumson, New Jersey, a group of young Cub Scouts conducted a two-day drive to collect objectionable comic books, which would be burned in Rumson’s Victory Park. The Scout that collected the most books won the right to light the blaze. At the last minute a decision was made to recycle and not burn the books. In Cape Girardeau, Missouri, a troop of Girl Scouts collected objectionable books and brought them to students at St. Mary’s, a Catholic high school, where a mock trial was held and, after finding the books guilty of “leading young people astray and building up false conceptions in the minds of youth,” the books were burned. In Chicago, a burning was organized by a Catholic Diocese. In Vancouver, Canada, nearly 8,000 comics were set ablaze by the JayCee Youth Leadership.

In a strange bit of irony, a large majority of the comics burned were produced by EC comics, who would later print adaptations of stories by Ray Bradbury, starting in 1952. A year later, in 1953, Bradbury would release Farenheight 451, a dystopian future in which books are burned and outlawed. But, what some people don’t know is that Farenheight 451 is based on a story called “The Fireman,” which in turn was based on a story named “Bright Phoenix.” “Bright Phoenix” was actually written in 1947, aligning the timing of the story with the early comic book burnings (and the now infamous Nazi book burnings in World War II). And while it is a known fact that the title of the book refers to the temperature at which paper burns, I’ll bet it took a considerably lower ignition point to destroy the low quality paper used in comics in the forties. As I was finalizing this posting, it was announced that Mr. Bradbury had died at the age of 91. The literary world has lost a giant.

As an interesting aside, I met Mr. Bradbury at one of his last appearances, where he told the story of how he came to work with EC Comics. The owners had copied two of his stories, putting them together into a single story. Bradbury sent a note praising them, while remarking that he had “inadvertently” not yet received his payment for their use. EC sent a check and together they released a series of Bradbury adaptations. I should also note that comic books and magazines survived in the world of Farenheight 451 because they weren’t worth worrying about.

Of course, many people reading this may think that book burning is nothing to worry about. They are a thing of the past, akin to a hate crime, and unheard of in today’s society. But, let’s not forget that, as recently as 2006, there have been several incidents of book burnings involving the Harry Potter franchise (I believe the Davinci Code was also burned earlier in the year). There were also Twilight burnings done by irate fans who wanted to show their displeasure to Stephanie Meyers (these readers eventually realized that returning the books sent a stronger message).

Book burning is the most severe form of censorship and who knows how many great books have been lost to history because of it. Of course, there also exist lesser forms of censorship that may be just as, if not more so, dangerous. I hope to explore those in the future because in the words of Ray Bradbury, “You don’t have to burn books to destroy a culture. Just get people to stop reading them.” Or if you prefer, as Henry Jones, Sr. (Sean Connery) said, “It tells me, that goose-stepping morons . . . should try reading books instead of burning them!”

And apparently, we are here again, with parent’s groups on one side and the comics industry on the other. I only hope, as this current debate rages on, that cooler heads prevail and things don’t escalate to censorship. Luckily, unlike 1948, there is better access to information and, for the most part, a more open minded view of the world. Plus, there are organizations like the CBLDF to pick up the fight should the wrong lines get crossed.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at www.joesergi.net.