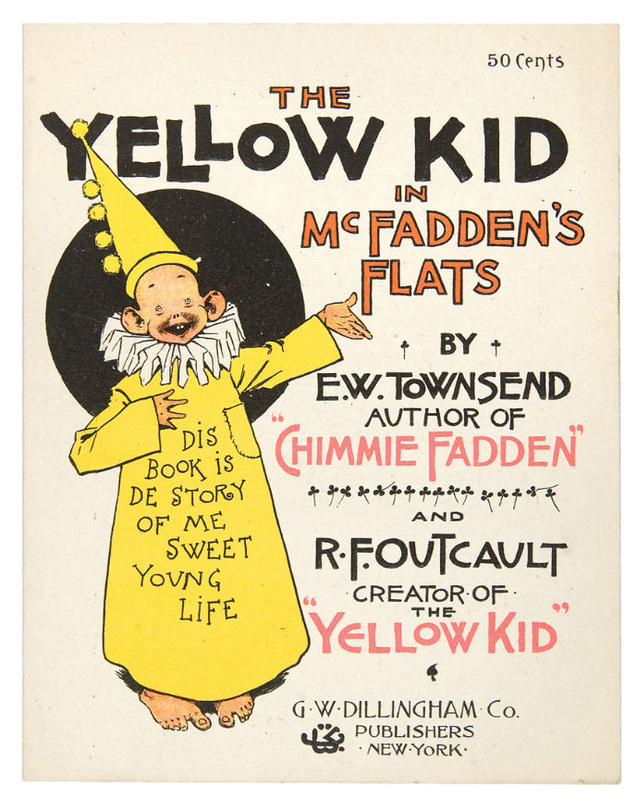

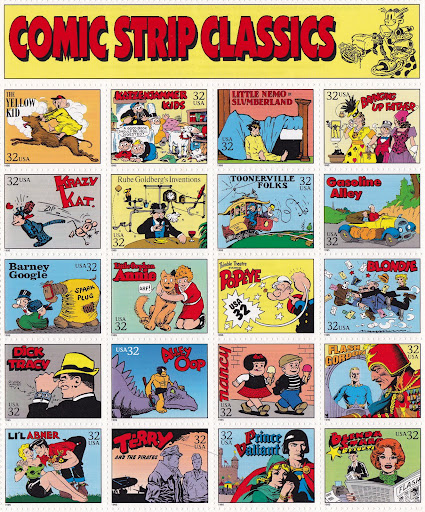

Many people know about the great comic book scare in the late ’40s and early ’50s. You know the one that started with individuals like Dr. Fredric Wertham and Senator Robert C. Hendrickson and ended with the creation of the now defunct Comics Code Authority. But what many people aren’t aware of is that comics had come under fire long before Dr. Wertham conducted his juvenile delinquency case studies in the Lafargue Clinic in Harlem, New York. This is a tale that goes back to very creation of the medium in the late 1890s, and starts with what many people consider the first comic: The Yellow Kid in McFadden’s Alley, published in 1897. (I should note that there is a debate as to whether The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck, created in 1842, more than fifty years earlier, is in actuality the first comic.)

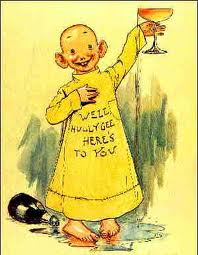

Like many early comics, The Yellow Kid in McFadden’s Alley did not have original material, but was a reprint of a newspaper strip. The material in The Yellow Kid in McFadden’s Alley first appeared in Hogan’s Alley, which starred the Yellow Kid and, debuting in 1895, was also one of the earliest weekly comic strips.

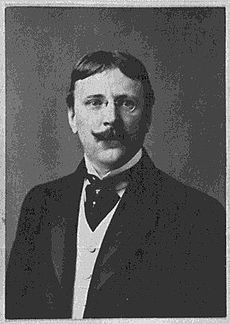

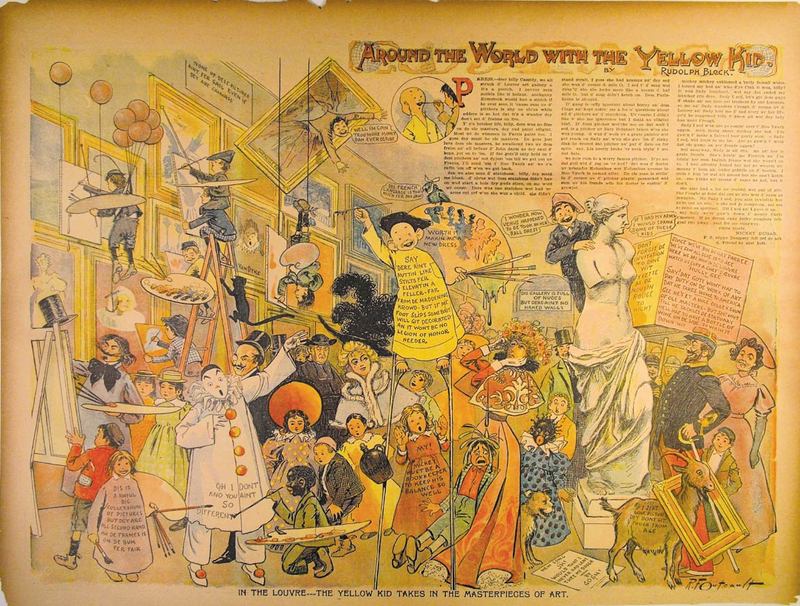

Created by Richard Felton Outcault and originally published in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World in 1895, Hogan’s Alley told the story of Mickey Dugan, the Yellow Kid. Mickey was a bald, snaggle-toothed boy who wore an over-sized yellow nightshirt and hung around in a slum alley typical of the time. This alley, called Hogan’s Alley, was filled with odd characters, mostly other children. With a goofy grin, the Kid habitually spoke in a ragged, peculiar slang printed on his shirt (which was tinted yellow by a brand-new color process). The humor and social commentary in Hogan’s Alley was aimed at Pulitzer’s adult readership and the series became a hit. Eventually, the success of the Hogan’s Alley came to the attention of William Randall Hearst, who owned the competing New York Morning Journal. Hearst believed that comics were key to selling newspapers (in part, because of the large immigrant population, whose first introduction to the English language was primarily through comics). As a result, Hearst lured Outcalt away from the World by offering him more money than Pulitzer. Consequently, The Yellow Kid left the World and joined the Journal in 1897.

Created by Richard Felton Outcault and originally published in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World in 1895, Hogan’s Alley told the story of Mickey Dugan, the Yellow Kid. Mickey was a bald, snaggle-toothed boy who wore an over-sized yellow nightshirt and hung around in a slum alley typical of the time. This alley, called Hogan’s Alley, was filled with odd characters, mostly other children. With a goofy grin, the Kid habitually spoke in a ragged, peculiar slang printed on his shirt (which was tinted yellow by a brand-new color process). The humor and social commentary in Hogan’s Alley was aimed at Pulitzer’s adult readership and the series became a hit. Eventually, the success of the Hogan’s Alley came to the attention of William Randall Hearst, who owned the competing New York Morning Journal. Hearst believed that comics were key to selling newspapers (in part, because of the large immigrant population, whose first introduction to the English language was primarily through comics). As a result, Hearst lured Outcalt away from the World by offering him more money than Pulitzer. Consequently, The Yellow Kid left the World and joined the Journal in 1897.

As an interesting aside, the term “Yellow Journalism” — originally “Yellow Kid Journalism” — came about because New York Press editor Ervin Wardman became enraged at the “Around the World With Yellow Kid” feature on the Journal‘s editorial page. As a result, he made reference to the “Yellow Press of New York” to describe the new kind of journalism represented by Pulitzer’s World and Hearst’s Journal, which excitedly elevated unimportant news; used irrelevant pictures, faked interviews and stories; and had a Sunday supplement with color comics. (Wardman’s rejected terms included “new journalism” and “nude journalism.”) In one of those great ironies in history, the name Pulitzer has since become synonymous with high standards and excellence in journalism. When the newspaper publisher died, he left money in his will to Columbia University to launch a journalism school and establish the Pulitzer Prize.

But, I digress. The Yellow Kid was a commercial success. In fact, he was the first comic strip character to have a his own line of merchandise, which included gum, cigarettes and toys. However, The Yellow Kid also raised the ire of censors and was labeled “vulgar” by its critics (a label Outcault did not necessarily dispute). Apparently, frequent letters were received by Journal readers asking the editor to reform this character, who was corrupting 1890s youth with his antics, and particularly because of the short nightgown he wore. (In response, Outcault drew an extra piece onto his character’s nightgown, extending it so that fell almost to his ankles.) In 1898, Outcault walked away from The Yellow Kid feature. (In 1902, he created Buster Brown, a Yellow Kid clone). But, Outcalt had paved the way for several other strips to follow, including The Katzenjammer Kid, Blackberries, Lady Bountiful, Mutt and Jeff and Hairbreadth Harry.

The disappearance of The Yellow Kid did not alleviate societal concerns about this new medium. In 1908, The New York State Assembly of Mothers Clubs, at its final session in Saratoga, placed itself on record as condemning “Yellow” newspapers and the Sunday comic sections of newspapers. Shortly thereafter, on October 31, 1908, the Boston Globe announced that it would no longer produce its comic supplement. The editorial page announced:

We discard it as we would throw aside any mechanism that had reached the end of its usefulness, or any feature that had ceased to fulfill the purpose of attraction.

Comic supplements have ceased to be comic. They have become as vulgar in design as they are tawdry in color. There is no longer any semblance of art in them, and if there are any ideals they are low and descending lower.

Despite this, by 1908, 75% of American Sunday papers had comics sections, and by the end of the 1910s, comics were nearly unavoidable in both daily and Sunday newspapers. As a result, they came under fire. Comic strips were thought to weaken the use of good manners, teach lawlessness, cheapen life, and increase the chance of mental illness. From 1910 through 1912, women’s groups, religious organization, and magazines campaigned to remove comic strips from newspapers. The Lady’s Home Journal argued that these brutal, unsophisticated strips were “A Crime Against Children.” Good Housekeeping and The Nation took issue with the fact that these amoral strips appeared in the Sunday editions of the newspapers (in color, no less), which was the Christian Day of Worship. Watchdog groups went as far as to argue that these comic strips would devalue the United States as a civilized nation and World Power.

In The Seven Lively Arts, Gilbert Seldes, a proponent of the medium, wrote:

In The Seven Lively Arts, Gilbert Seldes, a proponent of the medium, wrote:

Of all the lively arts the Comic Strip is the most despised, and with the exception of the movies it is the most popular. Some twenty million people follow with interest, curiosity, and amusement the daily fortunes of five or ten heroes of the comic strip, and that they do this is considered by all those who have any pretentions to taste and culture as a symptom of crass vulgarity, of dulness, and, for all I know, of defeated and inhibited lives. I need hardly add that those who feel so about the comic strip only infrequently regard the object of their distaste.

— The “Vulgar” Comic Strip (pages 213-228)

Battle lines were being drawn. But before things could escalate to the same level of attack that would later begin in the ’40s, a major change occurred in the business of comics strips: syndication. In 1912, Hearst formed the International News Service, which was the first service to create syndication of comics to newspapers (this would eventually became King Features Syndicate). Sadly, with syndication came censorship. Syndicates, like King Features and United Features (who distributed the popular strip Blondie), forbade references to divorce, race, and religion and outright banned the discussion of politics. In a strange parallel to the comic crisis that would later come, the industry essentially made the decision to censor itself under pressure from its critics. (I should also note that the rise of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan provided many watchdog groups with a more tangible threat and they turned away from their attacks on the strips to focus on the war. In short, the start of World War II meant that the war against newspaper strips ended, and the war against comics was deferred until Hitler could be defeated.)

Outcalt died in 1929, and his obituary read in part:

It is hard now to understand the fierceness with which staid observers denounced it in the nineties, the contempt with which foreigners spoke of its ‘childishness.’ Vulgar and banal it often was. But the critics failed to realize that there might be an evolution from the early crudity. Mr. Outcault’s Buster Brown, which marked a step up, consoled millions of youngsters for the boredom of Sunday without doing them any harm. Today the powerful Katrinka, the Toonerville Trolley, the shrinking Mr. Milquetoast, the affairs of Gasoline Alley and Mr. McCutcheon’s country-boy pictures are followed the country over. Some of them are merely amusing, hut others are more; they reflect cleverly and good-naturedly some phase of American life or character which deserves pictorial record.

Certainly, we should honor Outcalt’s contribution to the creation of comic strips and comic books. But we should also acknowledge the criticism and narrowly averted total censorship that this new medium drew almost from inception. Most importantly, we must remember to vigilant, lest history will repeat itself (as it did in the ’40s).

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net/.