Heroes Con in Charlotte, North Carolina, went down a few weeks ago. Unlike other larger conventions, which have expanded to become focused more on pop culture like television, movies and video games, Heroes Con is still a good old fashioned comic show and feels more like a family reunion. This year’s convention was special because it included Stan Lee, who I guess, keeping with the family analogy, is the really cool uncle that tells really fun stories about his adventures. You know, the one everyone loves but hardly ever gets to see. During the Annual Charity Art Auction, Stan Lee showed up to sign this painting by Phil Noto:

The audience was immediately on their feet. How could they not be? I mean, this was Stan “The Man” Lee. As I sat in the art auction, I thought about all the amazing things Uncle Stan had done for comics and how many great stories he must have about his experiences. With the Spider-Man movie out and Comic-Con wrapped up, I thought it would be fun to talk about the time that Stan Lee (and Marvel) challenged the Comics Code Authority and won.

Of course, one can’t mention comic book censorship without thinking of Fredric Wertham or his book, Seduction of the Innocent. In one of those great Stan Lee stories, Stan recounts, in his 2002 autobiography, Excelsior!, his frequent debates with Wertham. “He once claimed he did a survey that demonstrated that most of the kids in reform schools were comicbook readers,” Stan writes. “So I said to him, ‘If you do another survey, you’ll find that most of the kids who drink milk are comicbook readers. Should we ban milk?’ His arguments were patently sophistic, and there I’m being charitable, but he was a psychiatrist, so people listened.”

Stan Lee had been at Marvel/Timely/Atlas through the Werthem years. He experienced first hand the trouble caused by censorship of that time. In one interview, he described how, in 1957, after the public backlash against comics, he had to fire his artists, including Joe Sinnott, Dick Ayers, Gene Colan, Martin Nodell, Morris Weiss, Frank Bolle, and John Romita. “It was the toughest thing I ever did in my life. I had to tell them this. It was, as I say, the most horrible thing I ever had to do.” He told each of them, “I’m sorry, but there is no more work for you. It’s over. They were in shock, I was in shock.”

Stan had also been there when the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA) was formed in September 1954. The CMAA, under the leadership of New York Magistrate Charles F. Murphy created the Comics Code Authority (CCA), a self-policing code of ethics and standards for the comic book industry. The CCA responded to the public outcry by banning graphic depictions of violence and gore in crime and horror comics, as well as the sexual innuendo of what aficionados refer to as good girl art. Although this self-regulatory body appeared to calm the growing hysteria against comics, there was a large price to pay — free speech. The Code was de facto censorship. After its enactment, the number of comics on the stands dropped from 650 to around 250, and several companies (like EC Comics, Star Press, Sterling, Toby Press, Eastern Color, and the comic book division of United Features Syndicate) were forced out of business.

Stan had also been there when the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA) was formed in September 1954. The CMAA, under the leadership of New York Magistrate Charles F. Murphy created the Comics Code Authority (CCA), a self-policing code of ethics and standards for the comic book industry. The CCA responded to the public outcry by banning graphic depictions of violence and gore in crime and horror comics, as well as the sexual innuendo of what aficionados refer to as good girl art. Although this self-regulatory body appeared to calm the growing hysteria against comics, there was a large price to pay — free speech. The Code was de facto censorship. After its enactment, the number of comics on the stands dropped from 650 to around 250, and several companies (like EC Comics, Star Press, Sterling, Toby Press, Eastern Color, and the comic book division of United Features Syndicate) were forced out of business.

Most surviving comic companies had mixed feeling about the CCA. For example, Stan Lee stated in a 1988 interview, “I never thought about the Code when I was writing a story, because basically I never wanted to do anything that was to my mind too violent or too sexy. I was aware that young people were reading these books, and had there not been a Code, I don’t think that I would have done the stories any differently.” He added, in his autobiography, “Most of the changes seemed foolish and unnecessary to us, but they were easy to make and never bothered us that much. At least we were back in business again.”

But that didn’t mean there weren’t clashes. On the one hand, the comics professionals were trying to put out the best comics they could make. On the other, the CCA personnel were just trying to do their job. Of course, their requests did not always make sense. For example, Stan Lee’s Amazing Marvel Universe contains a story about how strange the limits on the size a puff of smoke could be under the CCA. Stan Lee described the incident as follows:

We did a western once. We had so many, I don’t remember which one. But at any rate, there was a panel where the hero shoots a gun and in the next panel, he knocks the gun out of the villain’s hand. And when he shot the gun, if you could visualize this, the gun is drawn in profile and, out of the nozzle of the gun, you see a puff of smoke, indicating that the shot had been fired, and a hand holding the gun — it was a close up. We sent the page to the Code and they sent it back and they said, ‘that panel had to be changed.’ And I said, ‘what on Earth is wrong with it?’ And they said ‘it’s too violent.’ And I said, ‘Why?’ Now, believe it or not they said, ‘the puff of smoke is too large.’ So, I gave it to one of the artists and he made the puff of smoke a little bit smaller. And we sent it back and they said, ‘oh, now it’s fine and they ok’ed it.” And I never knew that a large puff of smoke could be so injurious to young people when they look at it.

The remaining companies, like Marvel and DC, not only survived the CCA, but thrived under it. Stan was there when the industry revitalized in the Silver Age. In fact, Stan Lee was one of the impetuses behind that revitalization. Comics historian Peter Sanderson wrote:

The Marvel of the 1960s was in its own way the counterpart of the French New Wave…. Marvel was pioneering new methods of comics storytelling and characterization, addressing more serious themes, and in the process keeping and attracting readers in their teens and beyond. Moreover, among this new generation of readers were people who wanted to write or draw comics themselves, within the new style that Marvel had pioneered, and push the creative envelope still further.

Cary D. Adkinson, in his article, “The Amazing Spider-Man and the Evolution of the Comics Code: A Case Study in Cultural Criminology,” for the 2008 School of Criminal Justice, University at Albany Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture 15(3), expands on the importance of Spider-Man.

One such hero, introduced in 1962, helped revitalize a struggling genre and bring legitimacy to the medium itself. Peter Parker, the Amazing Spider-Man, revolutionized how superhero stories were told by confronting authority and the social ills that characterized the American cultural landscape during the Civil Rights Era. The mythos developed by co-creators Stan Lee and Steve Ditko created a universe in which “justice” depended on how characters used their power responsibly for the greater social welfare. In the mid-1960s Lee wove increasingly critical social commentary into the series, perhaps to cater to the sensibilities of the predominately college student audience, but certainly to preach the values of tolerance and responsibility to the general readership.

In short, the Marvel Age of comics had come and Spidey was leading the charge. As a result, in 1971, when Stan Lee was Editor in Chief, he was given the opportunity to do something that have considerable social consequence and would change the face of comics forever. Stan Lee tells the story as follows (in Les Daniels’ Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World’s Greatest Comics):

‘I got a letter from the Department of Health Education and Welfare.’ recalls Lee, ‘which said, in essence, that they recognized the great influence that Marvel Comics and Spider-Man have on young people. And they thought it would really be beneficial if we created a story warning kids about the dangerous effects of drug addiction. We were happy to help out. I wove the theme into the plot without preaching, because if kids think that you’re lecturing them, they won’t listen. You have to entertain them while you’re teaching.’

Roy Thomas and Stan Lee discussed this letter and the comic in Comic Book Artist #2:

Roy: Do you still have the letter from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare which prompted you to write the narcotics issues of Spider-Man?

Stan: There used to be a scrapbook in the office, and if it’s still around, the letter would be in there. I haven’t seen it in a million years. I got this letter — I don’t remember the exact wording — and they were concerned about drug use among kids. Since Marvel had such a great influence with young people, they thought it would be very commendable if we were to put out some sort of anti-drug message in our books.

I felt that the only way to do it was to make it a part of the story, and we made that three-parter of Spider-Man. I remember it contained one scene where a kid was going to jump off a roof and thought he could fly. My problem is that I know less about drugs than any living human being! I didn’t know what kind of drug it was that would make you think you could fly! I don’t think I named anything; I just said that he had “done” something.

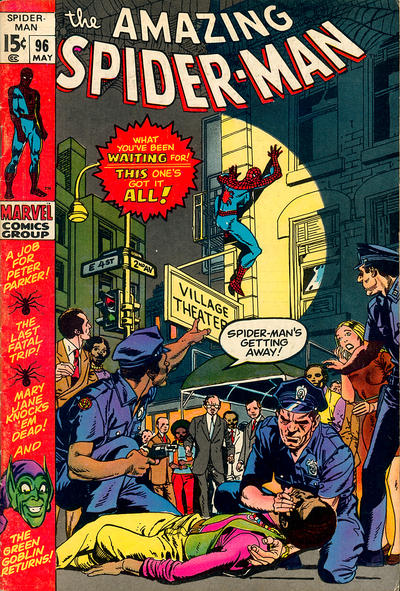

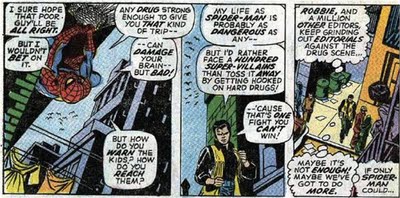

The three-part story appeared in Amazing Spider-Man issues 96 through 98 and were drawn by the amazing Gil Kane and John Romita, Sr. The story opens with Spider-Man saving a man who is high on drugs, dancing on a rooftop. Spidey says, “I would rather face a hundred super-villains than throw my life away on hard drugs because it is a battle you cannot win!” The main plot involving how Harry Osborn, Sr., had regained his memory and turned back into the Green Goblin. However, in an important subplot, Peter Parker is shocked to find Harry, his roommate and the son of the Green Goblin, popping pills, partly because his love interest Mary Jane Watson dumped him. Stan concludes the saga with the requisite fight between the Green Goblin and Spider-Man. However, Peter defeats the Goblin by showing him his sick son, which turns him back into Harry Osborne, Sr.

The three-part story appeared in Amazing Spider-Man issues 96 through 98 and were drawn by the amazing Gil Kane and John Romita, Sr. The story opens with Spider-Man saving a man who is high on drugs, dancing on a rooftop. Spidey says, “I would rather face a hundred super-villains than throw my life away on hard drugs because it is a battle you cannot win!” The main plot involving how Harry Osborn, Sr., had regained his memory and turned back into the Green Goblin. However, in an important subplot, Peter Parker is shocked to find Harry, his roommate and the son of the Green Goblin, popping pills, partly because his love interest Mary Jane Watson dumped him. Stan concludes the saga with the requisite fight between the Green Goblin and Spider-Man. However, Peter defeats the Goblin by showing him his sick son, which turns him back into Harry Osborne, Sr.

Stan was adamant that he didn’t want to be preachy:

I was determined not to allow the “message” part of our story to be so prominent, so blatant, as to make it seem like a sermon. I didn’t want our readers to feel we were preaching to them just because they were a captive audience — and yet, it was important that the message come across, loud and clear. The answer seemed to be to inject the theme of drug addiction as a peripheral sub-plot which would in no way dilute the action, drama, or suspense of the regular super hero theme.

“It was a good story and everyone involved was very happy with it.” Stan said in a later interview, “As usual, we sent the book to the CCA and, amazingly, and ironically, they said they had to reject it.” He expanded on this in Stan Lee’s Amazing Marvel Universe:

And when they were reading these [Spider-Man] stories, before they would put the seal of approval on the magazine, they said, ‘oh no, you can’t do this story.’ And I said, ‘why?’ They said, ‘according to the rules of the Code Authority, you can’t mention drugs in a story.’ And I said, ‘Look we’re not telling kids to take drugs, this is an anti-drug theme.’ [They said,] ‘Oh no it doesn’t matter, you mention drugs.’ And I said, ‘but the Department of Health Education and Welfare, a government agency, asked us to do it.’ and they said, ‘it doesn’t matter, you can’t mention drugs.’

Some interesting observations before I continue. First, the word drugs is not contained in the CCA and drug use was not specifically prohibited by the CCA. Instead, the comic ran afoul of a general section entitled Standards Part C, which prohibited “All elements or techniques not specifically mentioned herein, but which are contrary to the spirit and intent of the code, and are considered violations of good taste or decency.”

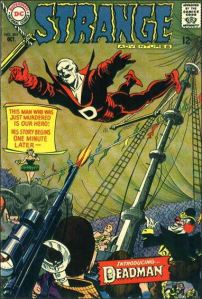

Second, as pointed out by Brian Cronin’s Comic Book Legends Revealed #226 on Comic Book Resources, at least one comic prior to the Spider-Man issues dealt with the topic of drugs. That comic was Strange Adventures #205, the first appearance of Deadman. In the story, Deadman takes on opium dealers in a book that received CCA approval and came out three years before Stan Lee submitted the Spider-Man stories.

Third, the decision to reject the book was not made by Leonard Darvin, the CCA administrator at the time because he was reportedly out sick when the Spider-Man issue came through for approval. As a result, Archie Comics publisher John L. Goldwater made the decision to reject the book. Several commentators have speculated that Darvin would have approved the issues. So, I can’t help but wonder that somewhere in the Blue Area of the Moon, Uato is asking “What if Darvin had approved Spider-Man 96?”

In any event, Stan was faced with a three-part story that was ready for publication, but one that the CCA refused to approve. In a controversial move, Stan decided that, “we would do more harm to the country by not running the story than by running it.” He added, in Michael Mallory’s Marvel: Their Characters and Their Universe that, “I felt that the United States Government somehow took precedence over the [CCA].”

So, Stan took the issue to Marvel’s Publisher, his cousin-in-law. On this, Stan told the story to Comics Alliance,

Well I was very proud of our publisher because I went to him. His name was Martin Goodman. I said, ‘Martin, you have got to let me send these three issues without the Code.’ He said, ‘gosh Stan, that’s taking a big step. I mean, we’re supposed to abide by the Code. And I said, “Yeah, but we’re supposed to do what the government tells us and I got this letter from Washington. And besides, this is a good thing. It’s letting kids know that drugs are harmful. This time he said, “Ok Stan, you go ahead and do it and I’ll back you up.”

So, for the first time since the inception of the CCA, Marvel sold their books without the seal of the CCA. Stan said, “I could understand them; they were like lawyers, people who take things literally and technically. The Code mentioned that you mustn’t mention drugs and, according to their rules, they were right. So I didn’t even get mad at them then. I said, ‘screw it’ and just took the Code seal off those issues. Then we went back to the Code again.” There was no explanation on the books as to why there wasn’t a seal, no rationalization and not even any mention of the request from Department of Health Education and Welfare. Nobody really cared that it wasn’t there. Stan recalls the reaction, “The world did not come to an end. We got the greatest mail from parents, teachers, religious organizations praising us for that story.” Stan Lee expanded on this to Kevin Smith in Mutants, Monsters and Marvels:

A funny thing happened there, too. The New York Times gave it a good write up. Now, as you probably know, when The New York Times has a feature story, other papers in the country pick up on it. Well, I would clippings from the other papers. But, what they would do, so often they would headline their stories something like “Marvel Comics Drug Issue Causes Controversy” and looking at the headline, you would think we were pushing drugs. So I learned there is no good you can do that doesn’t turn into something you are embarrassed by later.

During the Stan Lee: An American Icon panel at New York ComicCon a few years ago, Marvel’s Joe Quesada, mentioned that he got into comics because his father heard about the anti-drug storyline in Amazing Spider-Man, and wanted Joe to read these issues. But all of the reaction was not positive. Marvel drew criticism from DC head Carmine Infantino for defying the code. DC announced that they would not do any drug stories unless the code was changed.

And then the CCA changed. Or as Stan says, “I might add that it does have a happy ending. The Comics Code finally allowed a mention of drugs that can be done in a way like that.” As a result of Stan’s actions, the CCA began to look a little foolish and the member publishers amended the code to remove some of the more foolish provisions, which gave creators more freedom that was available in other media. Stan summed it up in an interview with IGN, when he said, “After the Code people learned of [the reaction to the anti-drug issues], they changed the Code and started to be a little bit more intelligent about what they objected to “ Specifically, the restriction against anti-drug messages was removed and the CCA revised the Code to say:

Narcotics or Drug addiction shall not be presented except as a vicious habit. Narcotics or Drug addiction or the illicit traffic in addiction-producing narcotics or drugs shall not be shown or described if the presentation:

(a) Tends in any manner to encourage, stimulate or justify the use of such narcotics or drugs; or

(b) Stresses, visually, by text or dialogue, their temporary attractive effects; or

(c) Suggests that the narcotics or drug habit can be quickly or easily broken; or

(d) Shows or describes details of narcotics or drug procurement, or the implements or devices used in taking narcotics or drugs, or the taking of narcotics or drugs in any manner; or

(e) Emphasize the profits of the narcotics or drug traffic; or

(f) Involves children who are shown knowingly to use or traffic in narcotics or drugs; or

(g) Shows or implies a casual attitude toward the taking of narcotics or drugs; or

(h) Emphasizes the taking of narcotics or drugs throughout, or in a major part, of the story, and leaves the denouement to the final panels.

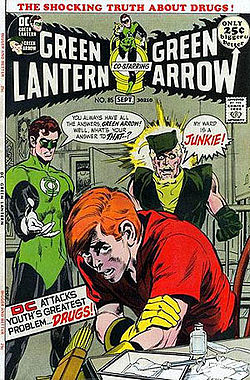

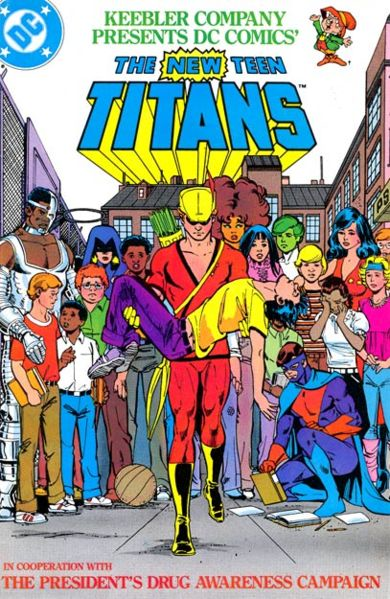

DC Comics eventually did its own anti-drug story in the pages of Green Lantern/Green Arrow, which had a plot in which Speedy, Green Arrow’s teenage sidekick, became a heroin addict. Speedy overcomes his addiction and helps other addicts kick the habit. Years later, First Lady Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” anti-drug campaign endorsed issues of The New Teen Titans in which Speedy and other teenage superheroes fought drug dealers, encouraged addicts to enter detox programs, and told kids not to try drugs. Of course, as we have seen the act of the Federal government had no sway on the CCA. And it all started with Stan’s Spider-man stories. As he puts it “This was a defining moment in the Comics Code Authority losing a lot of its authority.”

There is a Stan Lee quote in the Ten Cent Plague, by David Hajdu, that has always struck me as odd. He says, talking about the revitalization of comics and Marvel in the 1960s, “I knew how to keep it simple. [Marvel] wanted to give kids a good time and give them something positive to enjoy. We didn’t want to change the world.” As a matter of fact, Stan Lee did change the world for the better with the anti-drug Spider-Man issues.

But, if Stan had caved to the censorship of CCA, we would never have been able to read those issues. And that would have been a crime. ‘Nuff said.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net/.