On October 30, 1938, Americans believed that Martians had invaded the planet Earth because of realistic broadcast produced by Orson Welles’s Mercury Theater of the Mind. And while that broadcast created havoc and disarray, it was still considered protected free speech by the FCC. Years later, comics would not be given the same consideration.

On October 30, 1938, Americans believed that Martians had invaded the planet Earth because of realistic broadcast produced by Orson Welles’s Mercury Theater of the Mind. And while that broadcast created havoc and disarray, it was still considered protected free speech by the FCC. Years later, comics would not be given the same consideration.

It’s Halloween! Do you want to hear something really scary?

The year was 1938. Oversees, a politician named Adolph Hitler continued his rise to power. In the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was President, and the U.S. saw the creation of the March of Dimes and the establishment of a minimum wage. In January, Daffy Duck made his first appearance in the Merrie Melodies Cartoon named “Daffy Duck and Egghead.” Later in the year, Daffy was joined by an as yet unnamed Bugs Bunny, who appeared in “Porky’s Hare Hunt.” In April, comic books were forever changed as a strange visitor from the planet Krypton made his presence known in the pages of Action Comics #1. Howard Hughes flew around the world, and Joe Lewis knocked out Max Schemeling in the first round. Frank Capra’s You Can’t Take it With You was tops at the box office (and takes best picture and director the Academy Awards) and Artie Shaw’s Begin the Beguine topped the music charts.

On October 30, 1938, Martians invaded New Jersey and took over the world.

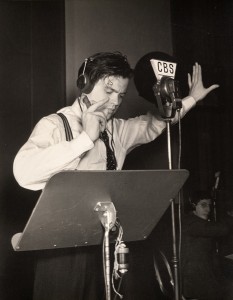

That night, more than six million CBS radio listeners tuned in and heard Orson Wells and his Mercury Theater perform HG Wells’s War of the Worlds. Most of the listeners realized it was a radio dramatization. But as many as two million people believed it was real and that they were hearing news reports of an alien invasion.

Now, to fully understand the impact of what occurred, one must realize just how important radio was to the American consciousness in 1938. Although there were some early code transmissions of news and weather broadcasts as early as 1909 and the first commercial broadcast license was issued to KDKA, which went on the air on November 2, 1920 (they broadcasted election results), radio was still in its infancy. By 1938, the major radio networks had only been on the air for about ten years. In that time, the influence of radio had grown exponentially. Not only did radio provide a variety of scripted programming, including musical performers, comedies, dramas, and soaps, but Americans could experience journalism in a way completely unheard of at the time.

Now, to fully understand the impact of what occurred, one must realize just how important radio was to the American consciousness in 1938. Although there were some early code transmissions of news and weather broadcasts as early as 1909 and the first commercial broadcast license was issued to KDKA, which went on the air on November 2, 1920 (they broadcasted election results), radio was still in its infancy. By 1938, the major radio networks had only been on the air for about ten years. In that time, the influence of radio had grown exponentially. Not only did radio provide a variety of scripted programming, including musical performers, comedies, dramas, and soaps, but Americans could experience journalism in a way completely unheard of at the time.

Previously, the American public relied on newspapers and magazines for their news. This was not only colder and more impersonal, but there was also a time lag between the event and the reporting, which further disconnected the narrator from the reader. With the introduction of radio, listeners could be invested in ways readers never could. For example, in 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt took advantage of radio to connect with his constituency through his Fireside Chats, in which he shared his vision for a prosperous America and sympathized with the people. Another example occurred in 1932, when the listening public became glued to their transistors after the son of the world famous aviator Charles Lindberg was kidnapped. People listened to the real-time sounds of war as Hans Von Kaltenborn became the first journalist to report from the front lines of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. Finally, people who had tuned in on May 6, 1937, heard an emotional Herbert Morrison cry of “the humanity” when the Hindenburg burst into flames.

It should also be noted that, leading up to the War of the Worlds, many radio stations had been broadcasting about threats to America. However, these were not imaginings of a Martian invasion that sprung from the mind of HG Wells. Instead, these were very real threats that came from the policies of Nazi Germany and the rise of Adolph Hitler. In fact, a month before War of the Worlds broadcast, more radios were sold during the Munich Crisis (September 12-30th 1938) than in any previous three-week period.

Americans knew a war was coming.

They just didn’t expect The War of the Worlds.

Orson Welles has joked that War of the Worlds made him a star. That is not necessarily accurate. While it is true that Welles was only 23 years old when War of the Worlds aired, he had been in radio for several years as the voice of “The Shadow.” In July 1938, Welles (with assistance from fellow actor and writer John Houseman) created “The Mercury Theater of the Air,” a weekly hour-long show that presented classic literary works performed by Welles’ celebrated avant garde Mercury Theatre repertory company. Prior to the War of the Worlds broadcast, the Mercury Theater was a sustaining program (which is a fancy way to say that it had no commercials) and had previously performed such classic works as Sherlock Holmes, Jane Eyre, and the Count of Monte Cristo. The show aired Sundays at 8:00 p.m. on 92 affiliated CBS stations. Unfortunately, Mercury went up against the “Chase and Sanborn Hour,” which was the most popular radio program of 1938. The star of the show was ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his dummy Charlie McCarthy, which is interesting since ventriloquism is a visual performance art. On Sunday nights, listeners would alternate between the two programs in the radio equivalent of today’s channel surfing. Welles was always looking for ways to increase his audience, hoping to take away listeners from the “Chase and Sanborn Hour.”

Orson Welles has joked that War of the Worlds made him a star. That is not necessarily accurate. While it is true that Welles was only 23 years old when War of the Worlds aired, he had been in radio for several years as the voice of “The Shadow.” In July 1938, Welles (with assistance from fellow actor and writer John Houseman) created “The Mercury Theater of the Air,” a weekly hour-long show that presented classic literary works performed by Welles’ celebrated avant garde Mercury Theatre repertory company. Prior to the War of the Worlds broadcast, the Mercury Theater was a sustaining program (which is a fancy way to say that it had no commercials) and had previously performed such classic works as Sherlock Holmes, Jane Eyre, and the Count of Monte Cristo. The show aired Sundays at 8:00 p.m. on 92 affiliated CBS stations. Unfortunately, Mercury went up against the “Chase and Sanborn Hour,” which was the most popular radio program of 1938. The star of the show was ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his dummy Charlie McCarthy, which is interesting since ventriloquism is a visual performance art. On Sunday nights, listeners would alternate between the two programs in the radio equivalent of today’s channel surfing. Welles was always looking for ways to increase his audience, hoping to take away listeners from the “Chase and Sanborn Hour.”

It is not clear as to whether War of the Worlds was planned as a radio hoax or whether Welles had any idea of the havoc it would cause. Welles initially denied it and later took credit for it and still later said he had a pretty good idea what would happen. However, the rest of the cast and crew really were apparently unaware of the ramifications the program would have.

A Time Magazine article reports:

When producer John Houseman suggested The War of the Worlds as the Mercury Theater’s Halloween eve broadcast, director and star Orson Welles laughed it off as silly and dull. Eventually, the idea surfaced to update the 1898 H.G. Wells story and split it into two. The first part would take the form of a series of musical pieces broken up by increasingly urgent news bulletins. No radio play before had toyed with the form like this, and the bulletins — at this point old hat to Americans familiar with the dire updates coming out of Europe — gave the story a sense of verisimilitude that it otherwise would have lacked.

Welles and Houseman were busy with a new play, so the writing duties were given to an up and coming playwright named Howard Koch. Given that his assignment was to update War of the Worlds into a series of news announcements, Koch had to pretty much rewrite the entire story as a play in less than a week. Koch told NPR about his process:

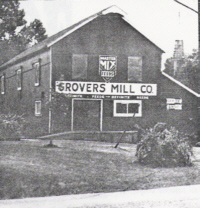

Coming down on the West Side of the Hudson River, I suddenly realized that if I was going to lay out this campaign, I better have a map…. I stopped at a gas station and they gave me a Jersey map. When I got to my apartment, I began work right away; I didn’t have much time. And I spread the map out, closed my eyes, put the pencil down, and it landed on Grover’s Mills. I thought, “Well, it has a good sound: American and real.”

Later that week after several rewrites, on Sunday, October 30, 1938 at 8:00 p.m., the broadcast began with the usual station identification and announcement:

The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations present Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre on the Air in The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells. Ladies and gentlemen: the director of the Mercury Theatre and star of these broadcasts, Orson Welles . . .

Welles then introduced the episode with his usual flair by reading a modified version of the first paragraph of HG Wells’s famous novel:

We know now that in the early years of the twentieth century this world was being watched closely by intelligences greater than man’s and yet as mortal as his own. We know now that as human beings busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinized and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinize the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacence people went to and fro over the earth about their little affairs, serene in the assurance of their dominion over this small spinning fragment of solar driftwood which by chance or design man has inherited out of the dark mystery of Time and Space. Yet across an immense ethereal gulf, minds that to our minds as ours are to the beasts in the jungle, intellects vast, cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes and slowly and surely drew their plans against us. In the thirty-ninth year of the twentieth century came the great disillusionment. It was near the end of October. Business was better. The war scare was over. More men were back at work. Sales were picking up. On this particular evening, October 30, the Crosley service estimated that thirty-two million people were listening in on radios.

However, most listeners did not hear this introduction. Later studies by CBS and the American Institute of Public Opinion found that between 40 and 50 percent of the listeners had tuned into the broadcast late. Instead, those listeners were tuned into the more popular “Chase and Sanborn Hour.” And, like they did each week, “The Chase and Sandborn Hour” spotlighted a musical feature at 8:12 p.m. And, like they did each week, listeners tuned into Mercury Theater. However, this week, instead of the usual dramatization of a play, listeners heard a breaking news bulletin that “a huge, flaming object, believed to be a meteorite, fell on a farm in the neighborhood of Grovers Mill, New Jersey, twenty-two miles from Trenton.” At around that time, Reporter Carl Philips gave the following “description”:

Well, I…I hardly know where to begin, to paint for you a word picture of the strange scene before my eyes, like something out of a modern “Arabian Nights.” Well, I just got here. I haven’t had a chance to look around yet. I guess that’s it. Yes, I guess that’s the…thing, directly in front of me, half buried in a vast pit. Must have struck with terrific force. The ground is covered with splinters of a tree it must have struck on its way down. What I can see of the…object itself doesn’t look very much like a meteor, at least not the meteors I’ve seen. It looks more like a huge cylinder. It has a diameter of…thirty yards.

Philips continues to interview people on the scene, including an expert, Dr. Pierson, who explains the object originated from the planet Mars, Suddenly the machine hums to life. The top of the object begins to screw off and Philips reports:

Good heavens, something’s wriggling out of the shadow like a gray snake. Now it’s another one, and another. They look like tentacles to me. There, I can see the thing’s body. It’s large, large as a bear and it glistens like wet leather. But that face, it… Ladies and gentlemen, it’s indescribable. I can hardly force myself to keep looking at it. The eyes are black and gleam like a serpent. The mouth is V-shaped with saliva dripping from its rimless lips that seem to quiver and pulsate. The monster or whatever it is can hardly move. It seems weighed down by…possibly gravity or something. The thing’s raising up. The crowd falls back now. They’ve seen plenty. This is the most extraordinary experience. I can’t find words…I’ll pull this microphone with me as I talk. I’ll have to stop the description until I can take a new position. Hold on, will you please, I’ll be right back in a minute.

Hal Davis, a publicity manager at CBS, explains what happened next.

Twelve or fifteen minutes into the program, the phone started ringing and the first one I picked up, a hysterical person said, “The Martians are invading, what do we do?”

Then, every phone began ringing at once. And everybody was hysterical. So, after about ten or fifteen minutes of this, I got somebody in the control room. And I said, “Hey, would you tell Orson Welles that people are taking this thing seriously? And they better put on a disclaimer.”

They came back and said, “Orson isn’t going to break into the program.”

About fifteen minutes after that, I guess, the operator called me panicked.

She said, “Hal, it’s gotten away from me.”

“I can’t handle it.”

Around that time, on the air, Reporter Phillips returned to the air with an “eyewitness account” of the alien attack:

Ladies and gentlemen (Am I on?). Ladies and gentlemen, here I am, back of a stone wall that adjoins Mr. Wilmuth’s garden. From here I get a sweep of the whole scene. I’ll give you every detail as long as I can talk. As long as I can see. More state police have arrived They’re drawing up a cordon in front of the pit, about thirty of them. No need to push the crowd back now. They’re willing to keep their distance. The captain is conferring with someone. We can’t quite see who. Oh yes, I believe it’s Professor Pierson. Yes, it is. Now they’ve parted. The Professor moves around one side, studying the object, while the captain and two policemen advance with something in their hands. I can see it now. It’s a white handkerchief tied to a pole…a flag of truce. If those creatures know what that means…what anything means!…Wait! Something’s happening!

A humped shape is rising out of the pit. I can make out a small beam of light against a mirror. What’s that? There’s a jet of flame springing from the mirror, and it leaps right at the advancing men. It strikes them head on! Good Lord, they’re turning into flame!

Now the whole field’s caught fire. The woods…the barns…the gas tanks of automobiles…it’s spreading everywhere. It’s coming this way. About twenty yards to my right…

Then, there were screams and a crash and then silence. Finally, an announcer solemnly stated

Ladies and gentlemen, due to circumstances beyond our control, we are unable to continue the broadcast from Grovers Mill. Evidently there’s some difficulty with our field transmission. However, we will return to that point at the earliest opportunity.

Meanwhile in the real world, all hell was breaking loose. There were reports of a nation-wide panic. According to the New York Times, 20 families in Newark, New Jersey rushed out of their houses with wet towels over their faces in order to protect themselves from Martian poison gas. In other places, panicked listeners packed roads, hid in cellars, and loaded their guns. In other cities, people begged police for gas masks to save them from the toxic gas and asked electric companies to turn off the power so that the Martians wouldn’t see their lights. One woman ran into an Indianapolis church where evening services were being held and yelled, “New York has been destroyed! It’s the end of the world! Go home and prepare to die!”

In the town of Grover’s Mills a group of town’s people listening in a tavern had gathered their shotguns and headed to the field. One of the townspeople reminisces:

In the town of Grover’s Mills a group of town’s people listening in a tavern had gathered their shotguns and headed to the field. One of the townspeople reminisces:

Now we get up there by the lake at Grover’s Mills and there’s nothing but a bunch of people — no hundred foot Martians. And, at that time, Orson Welles had not better show up anyplace near there.

In another altercation in Grover’s Mill, a group of listener shot a water tower thinking it was a Martian tripod.

Across the country the panic continued. The switchboard of newspaper offices and radio and police stations were rendered inoperable through the sheer number of calls asking how to flee their city or how they should protect themselves from “gas raids.” More than 2,000 calls came into the NYPD in less than fifteen minutes. The New York Daily news reported 1,100 phone calls and the New York Times switchboard reported 875 calls. And while no confirmed deaths stemmed from the broadcast, it is fair to say that the hysteria forced the government to devote considerable resources from their law enforcement, media, and municipal services to cope with the fallout from the program. Several people reportedly required medical treatment for shock and hysteria. In War of the Worlds: Behind the 1938 Radio Show Panic, Stefan Lovgen tells the story of Henry Brylawki, a Washington DC law student at the time:

I knew it was a hoax,” said Brylawski, now 92.

Others were not so sure. When he reached the apartment, Brylawski found his girlfriend’s sister, who was living there, “quaking in her boots,” as he puts it. “She thought the news was real,” he said.

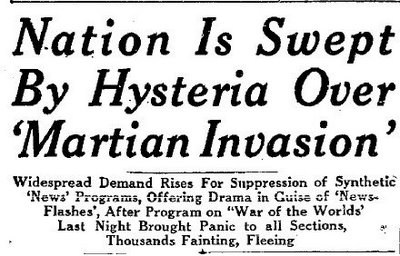

In the aftermath of the broadcast, newspapers had published over 12,500 articles about Welles’s War of the Worlds and its impact on the country. Headlines proclaimed, “Mars Invasion in Radio Skit Terrifies U.S.,” “H.G. Wells’s Book and Orson Welles’s Acting Bring Prayers, Tears, Flight, and the Police,” “Radio Fake Scares Nation,” and “Here’s the Story That Scared U.S.” In these articles, listeners claimed they could smell gas and see flashes of lightning from the Martian invasion. (I should add that some have argued that these articles were overstated and exaggerated in an effort by the print medium to denigrate the fledging radio industry that had replaced them as America’s primary news source.) Noted astronomers even visited the landing site in Grover’s Mills to see if they could find the meteorite that had fallen. A Harlem man insisted to The New York Times that he had heard “the President’s voice” over the radio advising all citizens to leave the cities. Richard J. Hand, author of Terror on the Air!: Horror Radio in America, 1931-1952, calculates “that some six million heard the CBS broadcast; 1.7 million believed it to be true, and 1.2 million were ‘genuinely frightened.'” Of course, Richards does not define what “genuinely frightened” means. Another estimate, in the book This is Orson Welles, Welles and Bogdanovich claim that up to 1,750,000 people were frightened enough by the broadcast to take some form of action.

Whatever the precise number, Orson Welles and CBS had a lot of explaining to do. Welles told reporters:

I’m extremely surprised to learn that a story, which has become familiar to children through the medium of comic strips and many succeeding novels and adventure stories, should have had such an immediate and profound effect upon radio listeners.

In other words, the “apology” was merely Welles expressing his surprise at how dumb people were for being duped by the program. Of course, what did he care? War of the Worlds did very well for the Mercury Theater. After the broadcast, the Mercury Theater received its first sponsor, Campbell’s Soup. Howard Koch would go on to win an Academy Award for Casablanca. And Welles landed a movie deal that would give him the creative control necessary for him to produce Citizen Kane. Of course, Welles never did earn back the public’s trust. Years later, Welles was once again on a radio network reading from the works of Walt Whitman when an announcement that Japan attacked Pearl Harbor interrupted the broadcast. Much of the audience recalled the War of the Worlds broadcast, suspected that Welles was up to his old tricks and refused to believe that the announcement was in fact real. President Roosevelt later wired Welles to suggest the inherent dangers involved in “crying wolf.”

But, the criticism did not end there. The day after the broadcast, Senator Clyde Herring stated that Welles’s drama was proof that radio needed “control by the government.” Newspapers ran headlines concerning lawsuits totaling $12 million which supposedly stemmed from the broadcast. And while several lawsuits were filed, none were ever decided. After the performance, listeners vented their emotions in writing. For example, 1,770 people wrote letters to the main CBS station (WABC in New York), and 1,450 wrote to the Mercury Theatre staff. Of these, it should be noted that 1,086 of the letters sent to CBS were complimentary. In addition, 91 percent of the letters received by the Mercury Theatre staff were positive.

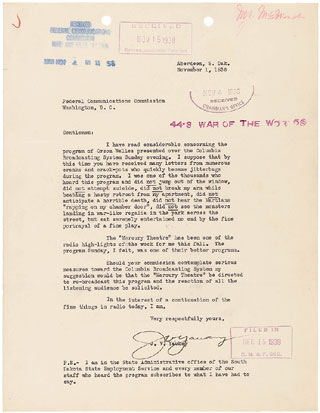

Add to those numbers the more than six hundred letters sent to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) — around 40 percent of the letters sent to the FCC were supportive of the broadcast. The FCC was only four years old and the War of the Worlds broadcast was its first real crisis. While the FCC was formed to regulate interstate and international communications, its charter specifically prohibited them from censoring broadcast material or from making any regulation that would interfere with freedom of expression in broadcasting. So, with War of the Worlds, the FCC was certainly at a crossroad with vocal opponents on both sides. Their strategy was to avoid any hasty action, lest it be construed as censoring program material.

Among the letters received by the FCC was one by singer Eddie Cantor, who wrote,

The Mercury Theater drama…was a melodramatic masterpiece…censorship would retard radio immeasurably and produce a spineless radio theater as unbelievable as the script of the War of the Worlds.

Perhaps in response, FCC Commissioner T.A.M. Craven made the following statement:

[T]he [FCC] should proceed carefully in order that it will not discourage the presentation by radio of the dramatic arts. It is essential that we encourage radio to make use of the dramatic arts and the artists of this country. The public does not want a “spineless” radio.

The issue was summed up in a New York Times editorial:

[The M]ail delivery yesterday morning brought 191 letters, and the bulk of these concerned Sunday evening’s nation-wide “invasion from Mars” radio scare.

Practically all our correspondents were in a rage when they wrote. About half of them were mad at the people who were hoaxed into taking the broadcast seriously; the other half were mad at Orson Welles, who put on the “War of the Worlds” radio rendition of H.G. Wells’s novel of the same title, for having done the job so vividly and convincingly.

We can’t work up a mad against either of these targets. ….

The only parties to the excitement that we’re mad at are the [FCC], for making such a fuss about it, and Senator Clyde L. Herring (Dem., Iowa), who has seized the incident as a pretext for renewing his drive for government radio censorship.

We wish the FCC would relax and go back to sleep. We hope the next Congress, and as many Congresses thereafter as necessary, will smack flat all radio censorship bills with the avalanche of “NO’s” they deserve in a free-speech, free-press, free-religion, free-assemblage country.

As predicted, in March 1939, Senator Herring fanned the flames when he wrote an article entitled “Is Radio Censorship Necessary?” in which he stated:

There has been a reluctance on the part of government to impose federal censorship, and it is quite certain that it will be resorted to only if other means of bringing about voluntary censorship fail.

Just as I am a staunch believer in the capacity of business to run itself and to set up, voluntarily, fair trade and labor practices for the governing of industry by management, so I believe that the radio industry is able to regulate itself.

The radio companies should voluntarily establish a code of ethics binding upon all broadcasters. This would at once obviate the necessity of further efforts at governmental control and, I believe, produce results infinitely more satisfactory from the standpoint of both the industry and the public….

In response, the FCC held an investigation concerning War of the Worlds, which coincided with a broader FCC hearing into problems concerning network broadcasting as a whole. The FCC completed its formal investigation into the War of the Worlds in just over one month from the date of the broadcast. On December 5, 1938, the FCC announced that it decided not to sanction the broadcast. Their release states:

The [FCC] announced today that in its judgment steps taken by [CBS] since the Orson Welles ‘Mercury Theater on the Air’ [sic] program on October 30 are sufficient to protect the public interest. Accordingly complaints received regarding this program will not be taken into account in considering the renewals of licenses of stations which carried the broadcast.

The [FCC] stated that, while it is regrettable that the broadcast alarmed a substantial number of people, there appeared to be no likelihood of a repetition of the incident and no occasion for action by the [FCC].

In reaching this determination, the [FCC] had before it a statement by Mr. W.B. Lewis, Vice President in charge of [p]rograms, of the [CBS], expressing regret that some listeners ‘mistook fantasy for fact’ and saying in part, ‘In order that this may not happen again, the Program Department hereafter will not use the technique of a simulated news broadcast within a dramatization when the circumstances of the broadcast could cause immediate alarm to numbers of listeners.’

The [FCC] had also heard a transcript of the program and had been informed regarding a number of communications concerning it. It was made known that the [FCC] received 372 protests against the broadcast, while 255 letters and petitions favoring it were received. Counting those who signed petitions, those who expressed themselves as favorable to the broadcast numbered approximately

Of course, some people believed that this was because radio had begun the process of self-censoring. Earl Sparling, writing for the March 1939 issue of American Magazine wrote:

On guard against government censorship, radio has clamped its own hand over its mouth in a self-censorship as rigid as, if not more rigid than, anything the government could order.

The jitters began with Mae West’s burlesque of the Garden of Eden, and reached chronic proportions with Orson Welles’s recent “War of the Worlds” debacle. Today broadcasters are scared silly. Their every decision is dictated by fear — fear of a club held over their heads by a handful of political appointees in Washington, the [FCC], who, in turn, are at the whim of any Nice Nelly in the country .

Radio was still not spineless, but it no longer had the vertebrae it once did. The FCC had to balance free speech with its mandate to protect the public. They came down on the side of free speech. Punishing artists could have a chilling effect on art. And they refused to do that.

In short, free speech and art had prevailed in 1939 in the battleground known as radio.

What a difference fifteen years make.

The same could not be said about the next battle, which would be fought over comic books. Perhaps more correctly, it should be known as the battle that was fought against comic books. Politicians, religious leaders, and psychologists vilified horror, crime, and superhero comics, all of which led to the brutal censorship of comics in the 1950s.

And like the FCC’s investigation of War of the Worlds, hearings were held, this time by the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency. As part of those hearings, Congress heard from William Gaines, the publisher of EC Comics, who volunteered to appear at the hearing. He was defiant in his testimony and met with disdain from the Senators. In short, his testimony was a public disaster and led to further public backlash against comics. Rather than defending free speech, this time the New York Times headline announced, “Crime publisher says shock comics in good taste.”

After the devastating Senate hearings, the comics industry was faced with an angry public and the fear of Congressional interference through adverse regulations. In response, the industry created the Comics Code Authority (CCA). Similar to the Association of Comic Magazine Publishers, the CCA sought self-regulate comics. Essentially, the CCA sought to sanitize comics and eliminated the crime and horror genres. Essentially, comics for older teens and adult disappeared for nearly fifteen years.

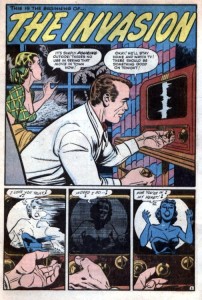

As an interesting illustration of the change in views, I wanted to take the broadcast of War of the Worlds and compare it to the prohibited comics. I chose a specific comic that was later re-released and censored under the Comics Code (which, of course, is based on the assumption that there was indeed something that needed censoring in the original comic).

The story is called “The Invasion,” and it appeared as a pre-Code story in Witches’ Tales #21 and then again as a post-Code story in Race for the Moon #1. Not only is this story is a great example of the type of changes that Code imposed, as it contains both major (a changed ending) and minor (removing cleavage) revisions, but it also tells the story of a couple listening to a War of the Worlds type broadcast. And gives the reader a glimpse into the dark reality behind such a hoax.

The book had its violent scenes remove because they violated General Standards Part A:

7. Scenes of excessive violence shall be prohibited. Scenes of brutal torture, excessive and unnecessary knife and gun play, physical agony, gory and gruesome crime shall be eliminated.

Take a look at a comparison of two scenes in the book with the post Code version on the right. Notice that the original text wasn’t changed. So now, without the additional art, the text doesn’t really make sense.

Interestingly, these panels pretty much illustrate the following scene from the radio play:

A humped shape is rising out of the pit. I can make out a small beam of light against a mirror. What’s that? There’s a jet of flame springing from the mirror, and it leaps right at the advancing men. It strikes them head on! Good Lord, they’re turning into flame!

So, while the radio was permitted to air descriptions of the men being killed (complete with sound effects), the protectionist Comics Code believed the same scene would have damaged the reader.

Here is the last page from the story (the pre-Code version on the left and the post-Code version on the right). First, you will note that the bodies have been removed from panel one (which must be why the husband looks calmer) and the alien is also less ugly in panel two.

This is interesting when you consider these two graphic descriptions of the aliens from the radio broadcast. First, from the creatures’ first appearance:

Good heavens, something’s wriggling out of the shadow like a gray snake. Now it’s another one, and another. They look like tentacles to me. There, I can see the thing’s body. It’s large, large as a bear and it glistens like wet leather. But that face, it…Ladies and gentlemen, it’s indescribable. I can hardly force myself to keep looking at it. The eyes are black and gleam like a serpent. The mouth is V-shaped with saliva dripping from its rimless lips that seem to quiver and pulsate. The monster or whatever it is can hardly move. It seems weighed down by…possibly gravity or something. The thing’s raising up. The crowd falls back now. They’ve seen plenty. This is the most extraordinary experience. I can’t find words…

Second, from the creatures’ last appearance.

Suddenly, my eyes were attracted to the immense flock of black birds that hovered directly below me. They circled to the ground, and there before my eyes, stark and silent, lay the Martians, with the hungry birds pecking and tearing brown shreds of flesh from their dead bodies. Later when their bodies were examined in the laboratories, it was found that they were killed by the putrefactive and disease bacteria against which their systems were unprepared…slain, after all man’s defenses had failed, by the humblest thing that God in His wisdom put upon this earth.

Of course, as can be seen, the ending of “The Invasion” is changed as well, from the original ending in which the husband kills his wife and them himself into an edited version in which they just pack their bags and go. Of course, the latter is what many would consider a weaker version. It’s hard to believe that the original version was considered harsher than this scene from the original War of the Worlds broadcast:

I’m speaking from the roof of the Broadcasting Building, New York City. The bells you hear are ringing to warn the people to evacuate the city as the Martians approach. Estimated in last two hours three million people have moved out along the roads to the north, Hutchison River Parkway still kept open for motor traffic. Avoid bridges to Long Island…hopelessly jammed. All communication with Jersey shore closed ten minutes ago. No more defenses. Our army wiped out…artillery, air force, everything wiped out. This may be the last broadcast. We’ll stay here to the end…People are holding service below us…in the cathedral. Now I look down the harbor. All manner of boats, overloaded with fleeing population, pulling out from docks. Streets are all jammed. Noise in crowds like New Year’s Eve in city. Wait a minute…Enemy now in sight above the Palisades. Five — five great machines. First one is crossing river. I can see it from here, wading the Hudson like a man wading through a brook…A bulletin’s handed me…Martian cylinders are falling all over the country. One outside Buffalo, one in Chicago, St. Louis…seem to be timed and spaced…Now the first machine reaches the shore. He stands watching, looking over the city. His steel, cowlish head is even with the skyscrapers. He waits for the others. They rise like a line of new towers on the city’s west side…Now they’re lifting their metal hands. This is the end now. Smoke comes out….black smoke, drifting over the city. People in the streets see it now. They’re running towards the East River…thousands of them, dropping in like rats. Now the smoke’s spreading faster. It’s reached Times Square. People trying to run away from it, but it’s no use. They’re falling like flies. Now the smoke’s crossing Sixth Avenue…Fifth Avenue….one hundred yards away…it’s fifty feet…

The transmission is then cut short by the sound of a body falling.

So what was different in the time between the Comics Scare and the FCC’s ruling? Perhaps the primary difference was in the timing. At the time of the War of the Worlds broadcast, America was in the Great Depression and fascist dictatorships in Europe and Asia were making overtures towards war. America held tight to its values and rights, including free speech. In essence, the FCC was saying they wouldn’t censor the radio because that is what fascists do. Americans were free.

After the war, society was looking for a new enemy and they found one: the growing problem of juvenile delinquency. When doctors like Fredrick Wertham explained that the problem could be fixed by eliminating the enemy known as comic books, many fought with the same enthusiasm that had defeated Hitler. Another difference was probably the fact that radio was for everyone and comics were viewed as primary for kids. If accurate, this reasoning is faulty for two reasons: first, the large number of children that listened to radio, and second, the large amount of adults that read comics (especially horror comics).

What is most interesting is that if you take all the comics ever printed, and assume that they are as bad as Wertham and his ilk say they are, the cumulative negative effect of these books comes nowhere near the panic, disruption or drains of government resources that was caused by Welles in a one hour broadcast. Despite this, comic books were nearly wiped out of existence and Welles was applauded for his magnificent hoax.

This article ends with the final words of Orson Welles on that night:

This is Orson Welles, ladies and gentlemen, out of character to assure you that The War of The Worlds has no further significance than as the holiday offering it was intended to be. The Mercury Theatre’s own radio version of dressing up in a sheet and jumping out of a bush and saying Boo! Starting now, we couldn’t soap all your windows and steal all your garden gates by tomorrow night…so we did the best next thing. We annihilated the world before your very ears, and utterly destroyed the C. B. S. You will be relieved, I hope, to learn that we didn’t mean it, and that both institutions are still open for business. So goodbye everybody, and remember the terrible lesson you learned tonight. That grinning, glowing, globular invader of your living room is an inhabitant of the pumpkin patch, and if your doorbell rings and nobody’s there, that was no Martian…it’s Hallowe’en.

And a reminder that the greatest threat to America may not come from outer space or even from overseas. Instead, it could come from the most well-meaning members of society. And that is something scary to think about on this Halloween.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net/.