In 1938, Superman took flight from the drawing board of a teenage boy named Joe Shuster into the pages of Action Comics. However, by 1954 Joe had fallen on hard times: He was no longer drawing Superman; he had lost a lawsuit to get his creation back; and his latest book, Funny Man, was a miserable flop. That is where the story takes a strange turn — one that leads to bondage, censorship, the Boy Hitler of Flatbush Avenue, The Supreme Court, and a German-born psychiatrist named Wertham. What follows is the amazing true story of Joe Shuster’s Nights of Horror and the Brooklyn Thrill Killers. Beware: It is not for the faint of heart.

In 1938, Superman took flight from the drawing board of a teenage boy named Joe Shuster into the pages of Action Comics. However, by 1954 Joe had fallen on hard times: He was no longer drawing Superman; he had lost a lawsuit to get his creation back; and his latest book, Funny Man, was a miserable flop. That is where the story takes a strange turn — one that leads to bondage, censorship, the Boy Hitler of Flatbush Avenue, The Supreme Court, and a German-born psychiatrist named Wertham. What follows is the amazing true story of Joe Shuster’s Nights of Horror and the Brooklyn Thrill Killers. Beware: It is not for the faint of heart.

Coincidence is a device commonly applied in fiction, and especially in comics. The X-Men’s car just happens to break down in front of Magneto’s hidden base. Peter Parker and Aunt May just happened to apply for a loan when Dr. Octopus robs the same bank. Or that time Batman and Superman just happen to be assigned the same cabin on a endangered cruise ship.

Readers are willing to suspend their disbelief, all the while knowing that such coincidences do not exist in the real world.

Or do they?

Sometimes fact is stranger than fiction.

This was very true in 1954, when the lives of several famous and infamous individuals crossed paths. As a result of this strange intersection, the wronged creator of comic’s greatest champion of morality would end up inspiring some of the most heinous crimes of the decade and would align the founder of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) with a German-born psychiatrist whose name would become synonymous with comic book censorship, over the banning of a book.

Our story starts with a fictional superhero.

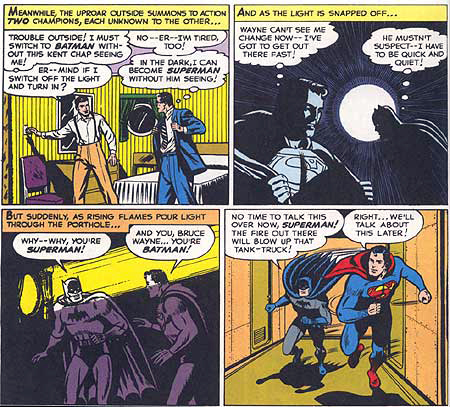

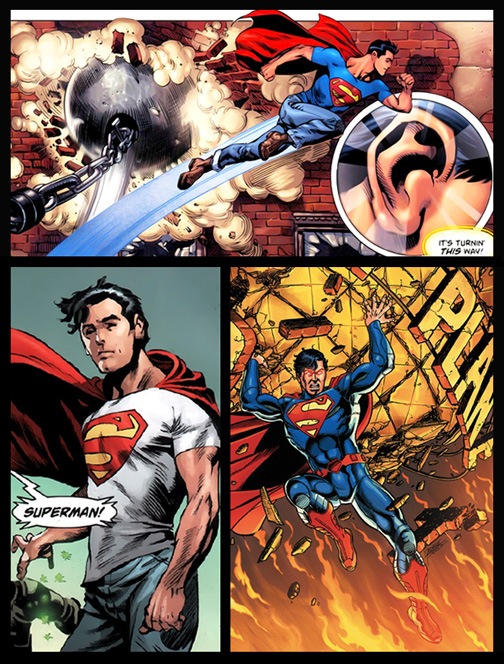

Superman, as everyone knows, is a strange visitor from the Planet Krypton, who possesses remarkable physical strength and fights a never-ending battle for truth, justice and the American way, and who, disguised as a mild mannered newspaper reporter Clark Kent, works for a major metropolitan newspaper. The character was created by two high school students, a writer named Jerry Siegel and an artist called Joe Shuster, who later sold their creation to a publisher named Harry Donenfeld for $130. Ironically, Donenfeld, a self-professed gangster, got his start publishing pornography, (with titles like Spicy Stories and Juicy Tales) before turning to making comic books, which featured characters such as the heroic and wholesome Superman.

Superman, as everyone knows, is a strange visitor from the Planet Krypton, who possesses remarkable physical strength and fights a never-ending battle for truth, justice and the American way, and who, disguised as a mild mannered newspaper reporter Clark Kent, works for a major metropolitan newspaper. The character was created by two high school students, a writer named Jerry Siegel and an artist called Joe Shuster, who later sold their creation to a publisher named Harry Donenfeld for $130. Ironically, Donenfeld, a self-professed gangster, got his start publishing pornography, (with titles like Spicy Stories and Juicy Tales) before turning to making comic books, which featured characters such as the heroic and wholesome Superman.

It turned out that wholesome was good for business, and Donenfeld earned millions on Superman. Siegel and Shuster, while well paid for their work, did not see anywhere near the amount of money Donenfeld did. As a result, in 1946 Siegel and Shuster filed suit to get back their creation. They failed. (A settlement was reached over the ownership of Superboy, but most of the money received went to pay their lawyer. As part of that settlement, Siegel and Shuster had to relinquish all rights to Superman, even the ability to say they were the creators).

It turned out that wholesome was good for business, and Donenfeld earned millions on Superman. Siegel and Shuster, while well paid for their work, did not see anywhere near the amount of money Donenfeld did. As a result, in 1946 Siegel and Shuster filed suit to get back their creation. They failed. (A settlement was reached over the ownership of Superboy, but most of the money received went to pay their lawyer. As part of that settlement, Siegel and Shuster had to relinquish all rights to Superman, even the ability to say they were the creators).

They also tried to create a new series called Funny Man with Magazine Enterprises, which also failed miserably. Between the lawsuit and the failed Funny Man series, Siegel and Shuster had apparently lost all of their money. Siegel, as a writer, eventually found employment with other comic publishers (and eventually returned to Superman). But Shuster, who had developed vision problems, could barely find work as an artist and had to pick up odd jobs just to survive, including illustrating erotic art for adult comic books and magazines.

By 1954, Shuster had fallen on hard times.

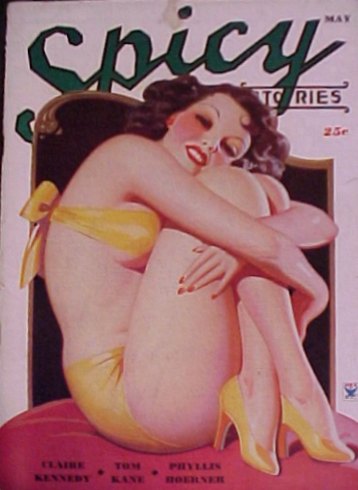

As the comic careers of Siegel and Shuster plummeted, Superman’s popularity soared. By 1954, Superman had become an American icon with appearances in comics, magazines, radio, and the cinema (both live action and cartoon formats).

As the comic careers of Siegel and Shuster plummeted, Superman’s popularity soared. By 1954, Superman had become an American icon with appearances in comics, magazines, radio, and the cinema (both live action and cartoon formats).

By 1954, Superman’s name became synonymous with fair play and the American ideal, and everybody loved Superman.

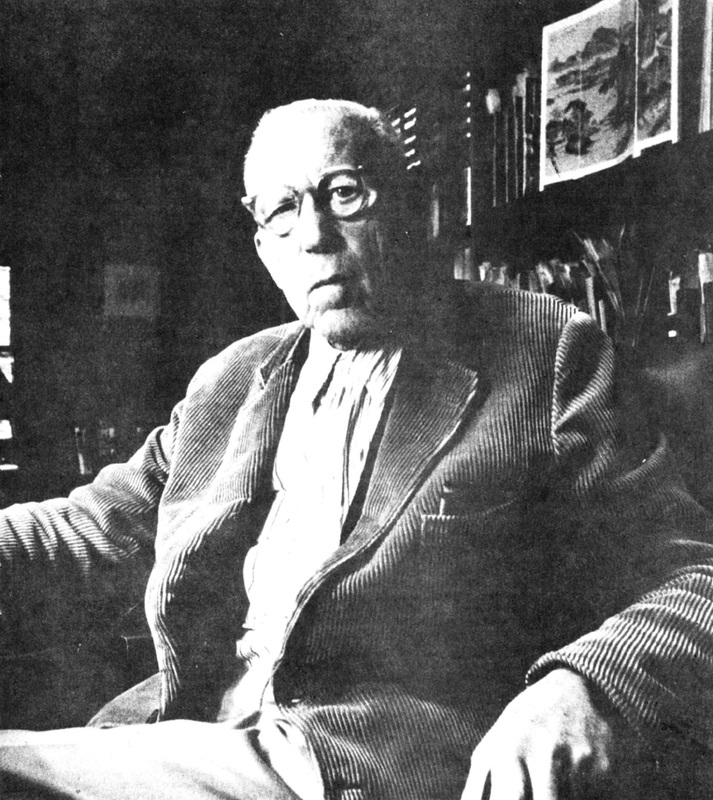

Everyone, that is, except for a German-born American psychiatrist named Fredric Wertham. Wertham had obtained some early notoriety in the 40s and early 50s for writing on the subject of juvenile delinquency. His articles had been published in Reader’s Digest and other, more scholarly, journals. In particular, Wertham had argued that comic books were the main cause of the increase in juvenile delinquency in America. Wertham hated Superman. He frequently singled out the character as a fascist and a Nazi. Moreover, Wertham wrote that Superman influenced children to only do good deeds for the sake of fame and potential rewards. He even went so far as to argue that Superman’s influence was so dangerous that the character encouraged children to create accidents and problems in order to be seen solving them. Despite these attacks, the Man of Steel only grew in popularity, which most likely annoyed Wertham.

Everyone, that is, except for a German-born American psychiatrist named Fredric Wertham. Wertham had obtained some early notoriety in the 40s and early 50s for writing on the subject of juvenile delinquency. His articles had been published in Reader’s Digest and other, more scholarly, journals. In particular, Wertham had argued that comic books were the main cause of the increase in juvenile delinquency in America. Wertham hated Superman. He frequently singled out the character as a fascist and a Nazi. Moreover, Wertham wrote that Superman influenced children to only do good deeds for the sake of fame and potential rewards. He even went so far as to argue that Superman’s influence was so dangerous that the character encouraged children to create accidents and problems in order to be seen solving them. Despite these attacks, the Man of Steel only grew in popularity, which most likely annoyed Wertham.

Not very many people are aware that Wertham, while against the comics industry, was actually sympathetic to Siegel and Shuster’s plight and was one of the earliest people to publicly write about their mistreatment by Donenfeld. He would later write in Seduction of the Innocent:

If I were asked to express in a single sentence what has happened mentally to many American children during the last decade I would know no better formula than to say that they were conquered by Superman. And if I were further asked what is the real moral of the Superman story, I would know no better answer than the fate of the creator of Superman himself.

John Kobler has written one of his magazine articles about the rise of Superman. It has a photograph of Jerry Siegal [sic], inventor of Superman, lying on an oversized, luxuriously accoutred bed with silken covers, in a room adorned with draperies. Here indeed is success. Kobler describes how Superman knocks out an endless procession of evildoers. “When a gangster rams Superman on the skull with a crowbar, the crowbar rebounds and shatters his own noggin.” Kobler does not fail to point out that Superman comes to children highly recommended. A child psychiatrist declared that Superman provides an inexpensive form of therapy for unhappy children.” So Superman and his inventor were well launched.

How did the Superman formula work for his creator? The success formula he developed did not work for him. Superman flies high in comic books and on TV; but his creator has long since been left behind.

By 1954, Wertham, a respected professional, was looking for some way to expand the reach of his message.

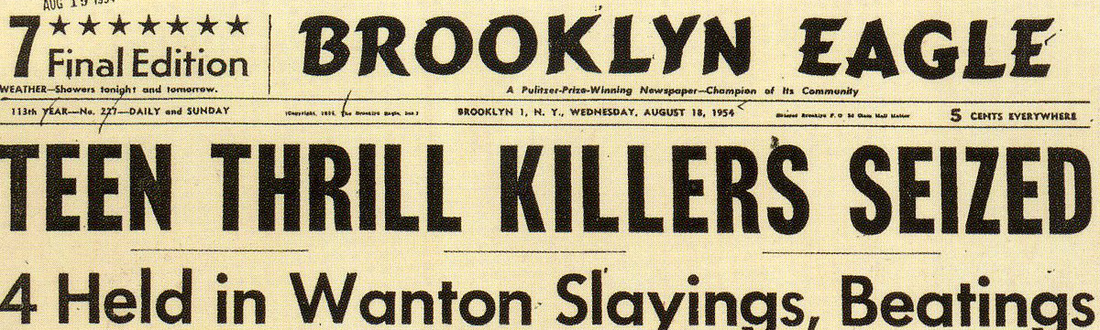

While Superman fought fictional villains, Joe Shuster struggled with poverty, and Wertham conspired to stop psychological terrors, a different kind of evil was being discussed in a New York City Courtroom in 1954. Senator Fred G. Moritt, attorney for the defense, approached the lectern for closing arguments as a hush fell over the courtroom. Once there, Moritt calmly spoke the words of poet John Donne, “Any Man’s death diminishes me.” The death Moritt spoke of was that of Willard Mentor, a 34-year-old black man that worked in a Brooklyn burlap bag factory.

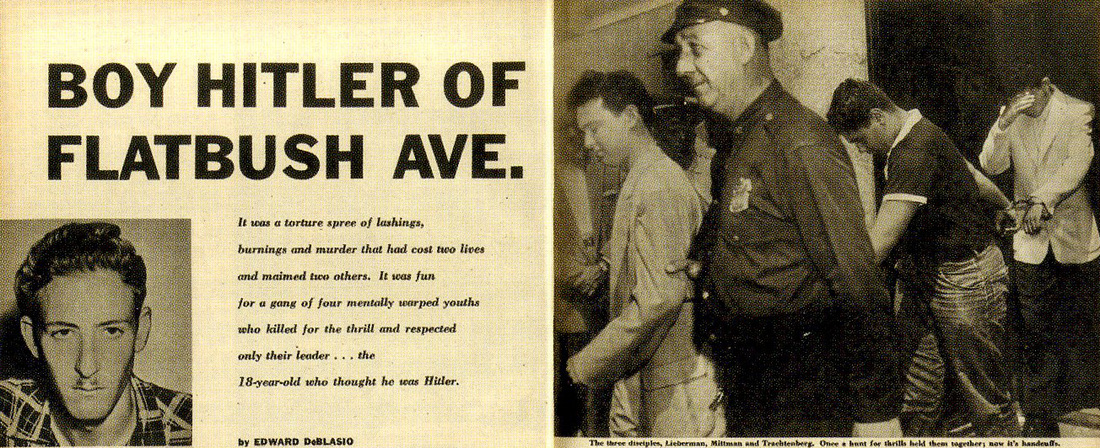

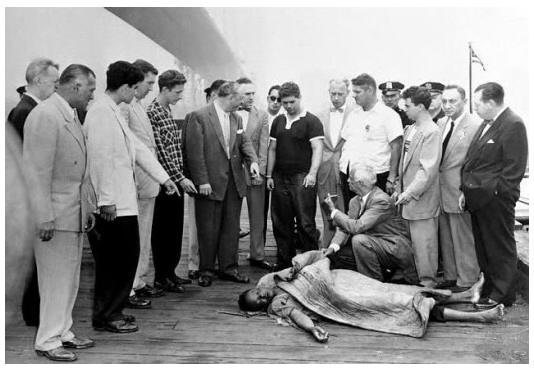

Mentor was sleeping off a drinking binge on a bench in George Washington Monument Park when he was attacked, beaten, and then drowned in the East River by the notorious teenage quartet known as the Brooklyn Thrill Killers. Jack Koslow, the leader of the teen gang, was a teenager with a Hitler mustache and a near genius IQ who believed that vagrants like Mentor were parasites on society. His second in command was Melvin Mittman, a musician who played the accordion, who liked “to use bums for punching bags to see how hard [he] could hit him.” Jerome Lieberman, the third member of the gang, played piano while the fourth and youngest member of the gang, Robert Trachtenberg, was a quiet and polite boy.

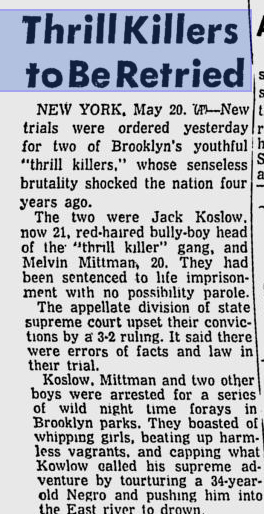

Together, these four teens roamed Brooklyn, flogging girls and terrorizing vagrants. Earlier in the year, Reinhold Ulrickson became the first victim to die at the hands of the Brooklyn Thrill Killers, when his skull cracked open by the boys. On the night they were arrested for the murder of Mentor, Lieberman and Trachtenberg appeared relieved, while Mittman and Koslow were belligerent and bragged that the murder was a supreme adventure. The Brooklyn Thrill Killer’s crimes and the trial received coverage in all the major newspapers and magazines. Time Magazine called the act “Senseless,” Life referred to the gang as “Those Terrible Young.” Inside Detective referred to Koslow as the “Boy Hitler of Flatbush Avenue.”

During the trial, the case against Lieberman was dismissed for a lack of evidence and Trachtenberg pled out in exchange for testifying on behalf of the prosecution. Moritt, who represented Koslow, was not an average attorney. A singer-songwriter (and member of ASCAP), Moritt dressed more like Billy Flynn from the Broadway Musical Chicago and less like Clarence Darrow and made highly theatrical objections. Still, during the trial Moritt had done his best to paint the boys’ action as mischief and, his citation of John Donne in his closing aside, to imply that Mentor’s death would not diminish anyone. The closing argument ended with Moritt reciting a poem he had written based on the children’s tale of “Ten Little Indians”:

Four little bad boys off on a spree,

One turned State’s evidence and then there were three.

Three little bad boys, what did one do?

The judge said, “No Proof,” and then there were two.

Two little bad boys, in court they must sit

And pray to the Jury, “please, please aquit.”

Pleased with himself, Moritt smiled as he sat down at the counsel table next to an equally-grinning Koslow, apparently oblivious to the fact that they were the only ones in the courtroom smiling.

The jury found the pair guilty of felony murder on the ground that the victim died during the commission of a kidnapping. Koslow groaned and put his arm around a weeping Mittman. With this verdict the jurors could — and did — recommend life imprisonment rather than the electric chair. Judge Hyman Barshay pronounced, “No judge, no court, no parole board will be empowered to release you from jail. The only possibility of your ever securing your liberty is through a pardon by the governor.”

By the end of 1954, Koslow and Mittman were serving life sentences.

So, how do the paths of a teen who co-created and drew Superman, a quartet of murderous teens, a German-born psychiatrist and the court’s system could possibly intersect. The answer lies with a series of books called Nights of Horror.

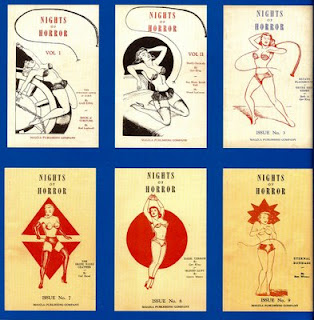

Nights of Horror was a black and white illustrated booklet produced by MaCla.

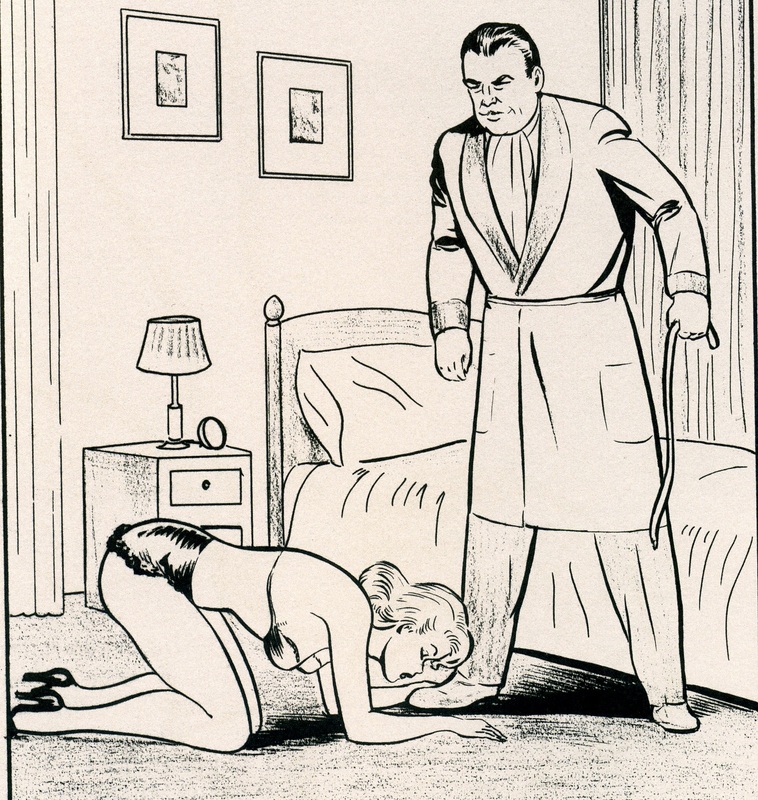

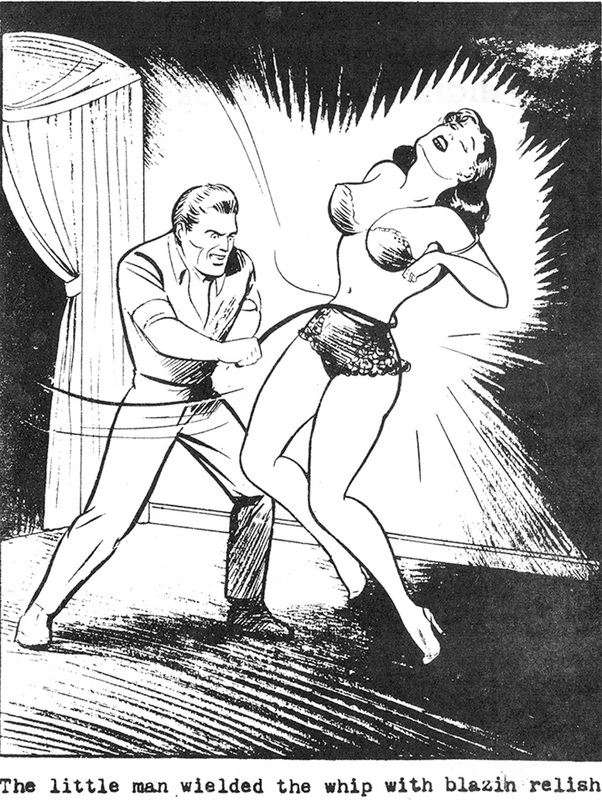

Nights of Horror had a small circulation and allegedly was only available in Times Square adult bookstores. The series lasted 16 issues. Each issue depicted sexual acts, bondage, and torture that ranged from women whipping men to men spanking women to women tying up women. It was by no means a professional publication. In fact, the text of each issue was not typeset or laid out and simply looked as if it was made using a simple typewriter and then photocopied. In essence, Nights of Horror had more in common with the Underground Comix market that became prevalent in the 60s and 70s than the other early comics of the 50s. Stories included text descriptions of sexual discipline and torture, mind control through drugs and hypnosis, and white slavery with titles like: “The Strange Loves of Alice,” “Devil’s Formula,” “Slaves of Gerardo,” “Slave Camp,” and “Flesh Merchants.” Each issue also featured comic illustrations that depicted the crude actions described in the courier font text. The art in Nights of Horror frequently included spanking, whipping, exhibitionism, and voyeurism, as well as interracial and lesbian couplings. Despite this, there was actually very little nudity in the book.

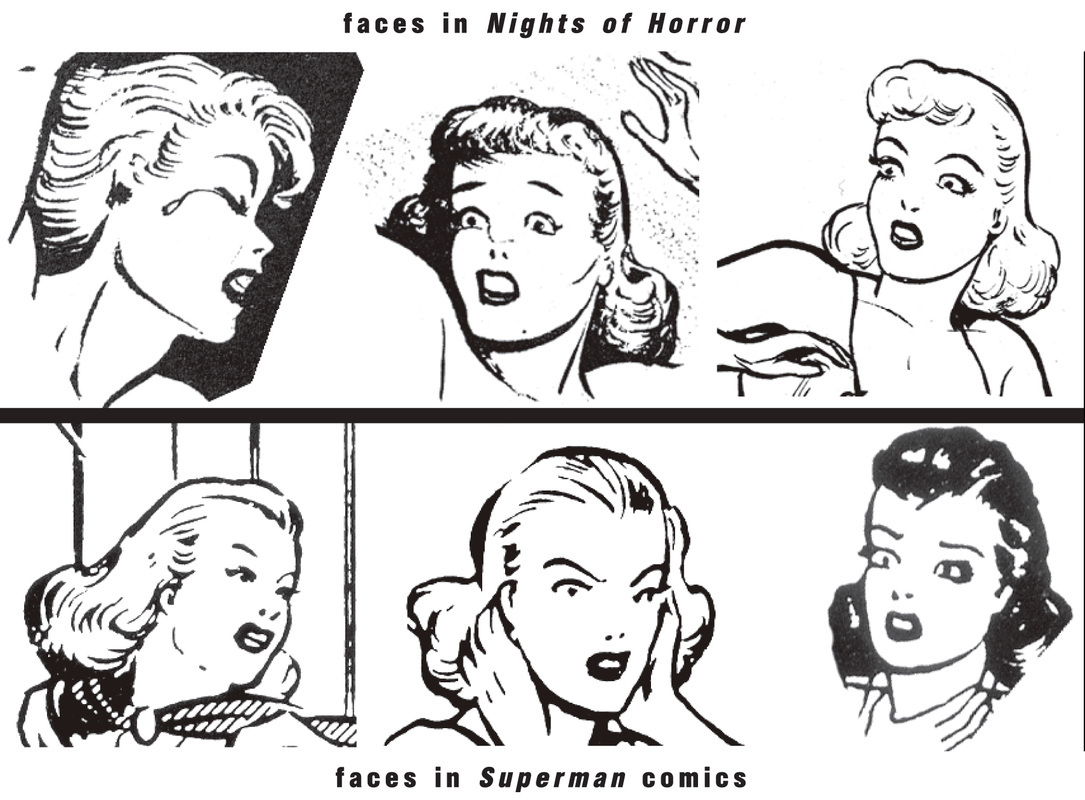

What was even more fascinating about this artwork is that even though the work was unsigned and uncredited, comics historian Craig Yoe discovered in 1989 that these pages were actually drawn by the co-creator of Superman, Joe Shuster. In an interview with Abrams Comics Art, Yoe explains how he made his discovery:

I spend a lot of time searching for old, rare comics art material online these days, but that’s usually best for going after items you already know about. Nothing beats combing through the vanishing flea markets, antique shows, and book sales for that once-in-a-lifetime discovery of material you never could have guessed existed. I first found these beautifully illustrated materials at a rare book sale in a dusty “adults only” box offered by an otherwise respectable dealer.

[His first reaction when he first realized whose work this was] . . . “Oh, my God, Joe Shuster!” The art was unsigned, but just as a criminal can be identified by his fingerprints, an artist’s work, even without a signature, can be unmistakable to the trained eye. This erotica had Joe Shuster written all over it. Because it’s by him, the art looks as if Superman, Clark Kent, Lois Lane, Jimmy Olsen, and Lex Luthor were in a porno flick — but of course it’s not really them at all! Soon after my discovery I showed this material to a high-up big shot at DC Comics who exclaimed, “Oh, my God, Joe Shuster!”

Yoe explands on this in his book, Secret Identity, The Fetish Art of Superman’s Co-Creator Joe Shuster:

The Art was technically some of Joe’s best. It was pure Shusterwork, without assistants or ghosts. It employed fine pen-and-ink work embellished by a favorite tool of the artist’s, lithographic pencil. Despite his weak eyesight handicap, Joe pushed and the results were sure and strong. Shuster always had a great ability to render attractive women, though in Nights of Horror they are more often sad victims than sassy vixens.

The artwork in the book was not only beautifully rendered, but also strangely familiar as Nights of Horror contained characters that looked a lot like Lois Lane, Lucy Lane, Clark Kent, Lex Luthor, Slam Bradly, Jimmy Olsen, Perry White and other supporting background characters in the Superman books.

And here is a page from Volume 3, that can only be Jimmy Olsen and Lucy Lane smoking pot.

Larry Tye, in his book Superman, The High Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero, offers some explanation for this and raises the question on everyone’s minds:

The best measure of Joe’s state of mind, and his finances, was the work he had taken but never breathed a word about: drawings of bare-skinned or nearly naked women being whipped, spanked, and humiliated by men and by other women. Joe didn’t sign the illustrations, but they were his.

* * *

Why did Joe do it? “Neither he nor Jerry could get work for anything decent so he had to tender that stuff to make a buck,” says his friend and Batman illustrator Jerry Robinson. “I don’t think that’s the work he would like to be remembered by.” Yoe, an author and former creative director for the Muppets, agrees but offers two additional theories: Depicting Superman characters in compromising poses might have been a way to strike back at Jack [Liebowictz] and Harry [Donnenfeld] for firing him and Jerry. It also could have reflected Joe’s fantasy life. “My guess,” Yoe concludes, “is that it’s probably some of all three of those things.”

Comic historian, Paul Buhle, writes in the The Jewish Daily Forward:

What do we learn from comic art images of women with whips, lesbian love (for male viewers presumably), assorted tortures and an excessive number of muscular buttocks, male and female? One wonders. One also wonders also if Shuster wondered at all. Possibly not. After he had been cheated out of a fortune, he took consolation from receiving a paycheck for creating familiar figures. [Secret identity] offers us a remnant of something as strange as it is repellant in American popular culture. Abominably produced, with diction errors and misprinted images, “Nights of Horror” could not have had much of an audience. But in a sense, it was the 1950s precursor to the next generations of adult magazines, films, DVDs and now Internet downloads, each new mode of distribution colonized and developed by porn.

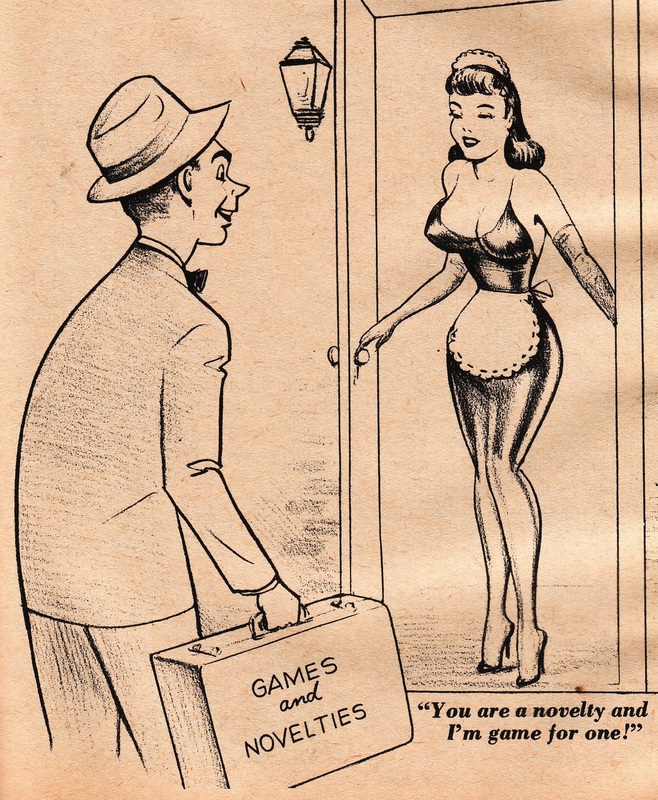

For completion sake, it should be added that Gerard Jones, in Men of Tomorrow, Geeks, Gansters and the Birth of the Comic Book, which predates Yoe’s book by several years, implies that Joe Shuster’s erotic work may not be limited to Nights of Horror:

When one follows the story of Joe Shuster through the 1950s, he seems to contract like the white dot of a television screen. For a year or two he apparently drew no comics at all. Sometime around 1951 or 1952 he seems to have found work with Charlton — not in its comics line but in its girlie magazines. There are some comic strips in low-rent titillation rags from Charlton and other publishers in the early Fifties, excuses for boob jokes mostly, that do look like a sloppy version of Joe Shuster’s art. A trace of the buoyant anatomy is still there. But Joe never admitted to the work, and no one really knows if it’s his. In 1954 he did his last real comic book work, a few issues of a Charlton crime comic. Then his confirmable credits disappear forever. There are more rumors, of girlie strips for Martin Goodman’s sleazy men’s magazines, of some sort of bottom- drawer gore rag called Night of Horrors (sic). Then even the rumors stop.

Here is an example of Shuster’s girlie work.

Nights of Horror, with its low quality production, limited audience, and low circulation, would have most likely have faded into obscurity and Joe Shuster’s artwork might never have come to light. But, then a connection was made between Nights of Horror and the gang known as the Brooklyn Thrill Killers from the court appointed expert.

As previously mentioned, the Brooklyn Thrill Killer trial received nationwide media coverage. As a result, by the end of the trial, the world knew who the killers were, the identity of their victim and the exactly how the crime was committed. But, what the world did not know, was why four normal teens from Brooklyn could have committed such outrageous crimes.

The answer to this question was offered by the Court’s appointed expert, Dr. Fredric Wertham, who served as senior psychiatrist for the Department of Hospitals in New York City and served as a director at mental-hygiene clinics at Bellevue Hospital and Queens Hospital Center. Wertham had initially been called in by Judge Barshay to determine whether Koslow was fit to stand trial or whether he was legally insane. Wertham concluded that Koslow was aware of his actions and knew right from wrong. Afterwards, Wertham received permission from Judge Barshay to examine Koslow. Through interviews, Wertham learned Koslow was a self-professed addict of Horror Comics and even had purchased a whip and cloak through ads in the book. The good doctor became intrigued. This interest could have only grown when Koslow informed him that Mittman was into “crime comics, you know, like Superman.” Shortly thereafter, Wertham brought 14 issues of the Nights of Horror comics to Koslow, each covered with a brown wrapper and asked if these were the kind of books he read. Koslow admitted that it was.

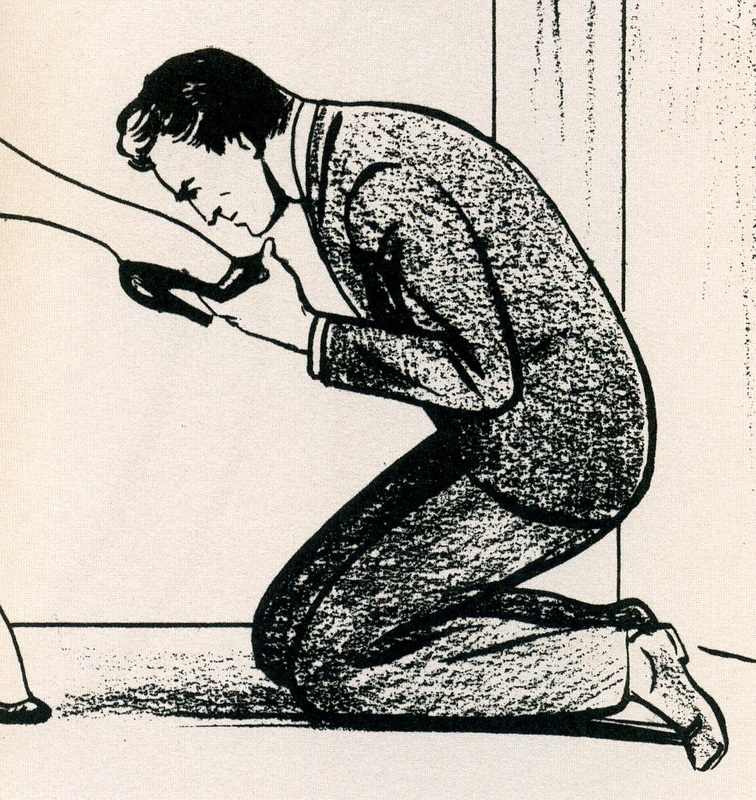

As a result, Wertham insisted that the books were to blame for the crimes of the Brooklyn Thrill Killers. In fact, Wertham even pointed to specific examples in Nights of Horror that “proved” that the comics were to blame. For example, Nights of Horror Volume 7 featured a scene where the victim was forced to kiss her attacker’s feet.

This scene also appears in Volume 5.

Marya Mannes explains this in her article, The ‘Night of Horror” In Brooklyn, which appeared in the January 27, 1955 of The Reporter:

“Nights of Horror” might leave the mature adult with no other reaction but disgust. What it might do to the immature — even the “normal” immature — is anybody’s guess. In any case, it is a fact that Koslow and his companions have tried most of the refinements in the series. He even told Wertham that they had made one of their beating victims kiss their feet in between blows and kicks, a scene clearly illustrated in “Nights of Horror.” “It is hardly something,” said Wertham, “that a boy would do spontaneously — that is, without getting the idea from somewhere.”

Wertham added, “All the horrible details [of the beating, kicking, and whipping committed by the Thrill Killers] are to be found in most of the comic books.” Wertham told the World Telegram, “I wish to emphatically point out that such crimes did not exist before this comic book era.”

It is interesting that Wertham’s conclusions, like much of his analysis related to comics and juvenile delinquency, lack proximate causation and any direct evidence that Koslow actually read Nights of Horror. For example, while it is true that Koslow admitted to Wertham that he read Nights of Horror, the admission did not come until Wertham showed him copies of the book. And even then, Koslow briefly looked at then before responding, “That’s it. Only I have a better edition.”

Koslow never specifically stated that he read Nights of Horror. No witnesses were ever produced by Wertham (or discovered since) that ever admitted to selling the boys these books, which were for targeted for adults only (several volumes were even labeled as such) and only available behind the counter in Times Square adult bookstores. Koslow was a teenager living in Brooklyn, so getting the books without assistance would have been problematic at the least. Given the books low circulation and the access limitations for teens, it is possible that Kolsow never even saw the book. Additionally, Koslow admitted to being a voracious reader of Mann, Pinoza, Nietzsche, and Mein Kampf. However, Wertham chose to ignore these other propaganda books and instead, concluded that comics were solely to blame for the youth’s behavior. Finally, it is entirely possible that Koslow was yanking Wertham’s chain. According to Mannes in The ‘Night of Horror’ in Brooklyn:

[Koslow] told Wertham (whose identity he was not told) that he was an addict of horror comics. “There’s some guy,” he said, “a psychiatrist — who keeps saying they have a bad effect on kids. I read about it in the Reader’s Digest. Listen — I could tell that guy something” since he admitted to having read the Reader’s Digest article by Wertham and boasted that he could “tell [Wertham] something.”

Given that Koslow was in a gifted program, graduated high school in three years, and taught himself German, it would not be hard to see a scenario where Koslow would recognize Wertham, feign ignorance, and then tell the psychiatrist exactly what he wanted to hear about ills caused by comic books. In this way, Koslow could emulate his idol, Hitler, a notorious censor and book burner.

It should also be pointed out that Wertham was worried about macabre images corrupting our youth and desensitizing them, yet the photograph of the Brooklyn Thrill Killers that ran in every major magazine and newspaper in the country (and reproduced above in the Brooklyn Eagle image above) clearly shows the bloody, beaten, and drowned corpse of Mentor.

Still, the Brooklyn Thrill Killers case was continuously cited in national publications such as Look (Chester Morrison, ʺThe Case of Brooklynʹs Thrill Killers: Could This Happen to Your Boy,ʺ Look, November 2 1954), Life (ʺQuiet Boys. And Horror,ʺ Life, August 30 1954), Newsweek (ʺThese Terrible Young,ʺ Newsweek, no. August 30 (1954)), The New York Times (ʺ4 Teen‐Agers Seized in Death by Kicking,ʺ New York Times, Aug 18, 1954), Reader’s Digest (T.E. Murphy, ʺThe Face of Violence,ʺ Reader’s Digest 1954), and The Saturday Evening Post (Clendenen, ʺThe Shame of America: The Post Reports on Juvenile Delinquencyʺ) to demonstrate the lurking threat of juvenile delinquency in American society. And Nights of Horror became the easy target to blame for the actions of the Brooklyn Thrill Killers.

Still, the Brooklyn Thrill Killers case was continuously cited in national publications such as Look (Chester Morrison, ʺThe Case of Brooklynʹs Thrill Killers: Could This Happen to Your Boy,ʺ Look, November 2 1954), Life (ʺQuiet Boys. And Horror,ʺ Life, August 30 1954), Newsweek (ʺThese Terrible Young,ʺ Newsweek, no. August 30 (1954)), The New York Times (ʺ4 Teen‐Agers Seized in Death by Kicking,ʺ New York Times, Aug 18, 1954), Reader’s Digest (T.E. Murphy, ʺThe Face of Violence,ʺ Reader’s Digest 1954), and The Saturday Evening Post (Clendenen, ʺThe Shame of America: The Post Reports on Juvenile Delinquencyʺ) to demonstrate the lurking threat of juvenile delinquency in American society. And Nights of Horror became the easy target to blame for the actions of the Brooklyn Thrill Killers.

By the end of 1954, the public was crying out for action.

The New York Legislature responded. The New York State Joint Legislative Committee to Study the Publication of Comics was first convened in 1949 to address the growing concern about the effect of comics and began issuing annual reports. On February 4, 1955, the focus of the Committee turned to Nights of Horror. Not surprisingly, Fredric Wertham was the star witness at their hearing. He testified as follows:

Paramount as a direct causative contributing factor in these acts of violence was what [Koslow] read. Koslow fancied himself a super-man. He graduated from crime and superman comic books, which he read in his childhood. He became steeped in horror comics, his mind becoming filled with all the thrill of violence, murder, and cruelty described in them.

* * *

In addition, [Koslow] was an addict of the type of pornography horror literature which is closely allied to comic books, although in a different format. He told me he read every volume of Nights of Horror, and… said he had been fascinated and emotionally overwhelmed by them.

* * *

In my opinion, if the community does not completely abolish the sale of crime and horror comic books and the type of literature of Nights of Horror to children, all attempts to curb this kind of violent crime by young people are sheer hypocrisy of self deception. It is deeply shocking to me as a psychiatrist and criminologist that two boys have to spend the rest of their lives in jail while the profiteers of this instigating material are not even fined two dollars. They are not only accessories but, in a strictly scientific sense, they incite the youngsters to act.

What makes this testimony interesting is the references to “super-man” and “superman comics,” which he distinguishes from crime books. This is inconsistent with Wertham’s writings and views expressed to Congress. (“This Superman-Batman-Wonder Woman group is a special form of crime comics”). I can only imagine how this testimony would have changed if Wertham ever found out that the co-creator of Superman was also the artist of Nights of Horror.

Soon after the hearings, the Committee released The Report of the NY State Legislature Committee to Study the Publication of Comics and concluded that

An analysis of the reading material of [the Brooklyn Thrill Killers] should serve for all time as a perfect example of the contribution made to delinquency, by those who place in the hands of youth cheap, sordid, perverted, and obscene blueprints for the crimes they commit. Koslow, the leader of the gang, had read all [sixteen] editions of a book called Nights of Horror, paper-bound books selling for and portraying all types of brutality, illicit, sex, and perversion.

Apparently, Wertham’s testimony, bolstered by a chart that compared the Thrill Killer’s actions to acts described in the book, convinced the Committee that Koslow not only read the book, but was a committed collector of Nights of Horror and was able to obtain every volume of the series.

As a result of this report, New York Mayor Wagner ordered police to clean up New York. On September 8, 1954, a new campaign to remove objectionable books, comics, and magazines from bookstores was launched under a newly-passed obscenity statute. Obviously, Nights of Horror would be at the top of the list of books for removal.

Two days later, on September 10, 1954, the Corporation Counsel of the City of New York sought an injunction against several book stores, for the purpose of: (1) permanently enjoining the stores from acquiring, selling or distributing Nights of Horror; (2) directing the bookstores to surrender to the Sheriff of the County of New York all issues of Nights of Horror; and (3) directing the Sheriff to seize and destroy the books. Shortly thereafter, the police raided Times Square book stores and seized 2,650 copies of Nights of Horror under the new obscenity laws.

In response, Kingsley Books (one of the book stores located in Times Square) responded to the injunction, denied the allegation of the complaint that Nights of Horror was obscene, and raised several Constitutional arguments including freedom of the press and unreasonable seizures.

A bench trial was held where members of the police force testified that the booklets had been displayed for sale in defendants’ stores and that they had purchased a number of copies from the various defendants, at prices ranging from $ 2 to $ 4 each. The publications themselves were also introduced in evidence. Judge Matthew Levy, who presided over the case, provided a thorough description of the books:

“Nights of Horror” is no haphazard title. Perverted sexual acts and macabre tortures of the human body are repeatedly depicted. The books contain numbers of acts of male torturing female and some vice versa — by most ingenious means, [which the Court describes in detail]…. The volumes expressed a philosophy of man’s omnipotent physical power over the female of the species. On occasion, the young woman is said to have gained satisfaction from the brutal beatings and horrible tortures. If she did not enjoy them, she received the beatings and tortures anyway — until she submitted to the sex acts desired by her tormentor. These brutalities were “my supreme pleasure” to the male, and resulted in “I’ll be your slave” to the female. (It is not to be taken that I have, in any measure, given a complete report of the “Nights of Horror.” I felt that I had to mention some, not the most sordid, features of this publication in view of the serious issues raised in this case — but I need not, I think, describe all I was compelled to read.)

Judge Levy was clearly not a fan of Nights of Horror. He wrote:

These booklets are not sex literature, as such, but pornography, unadulterated by plot, moral or writing style. That there is no attempt to achieve any literary standard is obvious. Each issue is a paper-covered booklet of from seventy to ninety-six pages, with a suggestive sex drawing on the front cover under the caption “Nights of Horror”. The price varies from $1.98 to $3 per issue. The volumes are replete with misspelled words, typographical errors, faulty grammar, misplaced pages and generally poor workmanship. While these factors do not, of course, classify the issues as pornographic, they are somewhat helpful in ascertaining whether there truly exists a genuine literary intent. “Nights of Horror” makes but one “contribution” to literature. It serves as a glossary of terms describing the private parts of the human body (notably the female breasts, buttocks and vagina), the emotions sensed in illicit sexual climax and various forms of sadistic, masochistic and sexual perversion.

As a result, the Court concluded:

The authors have left nothing to fantasy or to the unimaginative mind. The volumes are vividly detailed and illustrated. The many drawings that embellish these stories are obviously intended to arouse unnatural desire and vicious acts. Violence — criminal, sexual — degradation and perversion — are the sole keynote. Sadism and masochism are pictured as appropriate characteristics of human nature and pleasure. In short, the volumes of “Nights of Horror” in evidence before me are obscene and constitute pornography — “dirt for dirt’s sake”, bestiality, lust, crime, horror, for their unfortunate sake — and for the ugly sake of filthy commerce in human weakness.

In short, the trial court found that the volumes of Nights of Horror were plainly obscene and pornographic and held that the obscenity statute did not violate any Constitutional guarantees. On this, the Judge Levy again pointed to the base nature of the books as a justification.

Were the “Nights of Horror” works which indicated the slightest effort to contribute to our culture or knowledge, I might find myself in the position of “holding my nose with one hand” and “upholding with the other the right of free speech” that they are claimed to represent. But the volumes before me are so totally lacking in merit, and so obviously pornographic in intent, that their banning poses no threat to freedom of expression in literature or otherwise.

This concern was reiterated later in the opinion when the judge noted:

I do not consider censorship generally in the best public interest; and I would take a different view of literature even though it contained matter involving sex and crime. But the proof submitted on behalf of the plaintiff, a reading of the several issues of the “Nights of Horror“, the studies and reports of the New York State Joint Legislative Committee to study the publication of comics, of the Special United States Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, and of the Select Committee of the United States House of Representatives on Current Pornographic Materials, and our everyday observations of the shocking rise of juvenile delinquency and sex crimes – all these lead us more easily to read the scale of public interests which plead for the suppression of these publications. All these indicate such a clear and present danger of substantive evils that, as a judge, I cannot ignore the cry unless the Constitution says I must. I do not find that it does.

As a result, the Court enjoined further distribution of Nights of Horror and ordered their destruction of existing copies. The court did refuse to enjoin the sale and distribution of later issues that might be published upon the ground that “to rule against a volume not offered in evidence would… impose an unreasonable prior restraint upon freedom of the press.”

Kingsley Books appealed the ruling and the case went all the way up to the United States Supreme Court — the first to involve a banned comic book. However, Kingsley Books had abandoned its obscenity argument and did not challenge the trial court’s finding that Nights of Horror was obscene. Instead, the bookstore relied solely on the ground that the statute involved was an unconstitutional prior restraint and that it was entitled to a trial by jury. The Supreme Court upheld, five to four, the ruling of the trial court (as affirmed by the New York Court of Appeals). The majority was written by Mr. Justice Felix Frankfurter, who had previously founded the ACLU. He wrote:

In an unbroken series of cases extending over a long stretch of this Court’s history, it has been accepted as a postulate that ‘the primary requirements of decency may be enforced against obscene publications.’ And so our starting point is that New York can constitutionally convict appellants of keeping for sale the booklets incontestably found to be obscene.

* * *

It is not for this Court thus to limit the State in resorting to various weapons in the armory of the law. Whether proscribed conduct is to be visited by a criminal prosecution or by a qui tam action or by an injunction or by some or all of these remedies in combination, is a matter within the legislature’s range of choice . . . If New York chooses to subject persons who disseminate obscene ‘literature’ to criminal prosecution and also to deal with such books as deodands of old, or both, with due regard, of course, to appropriate opportunities for the trial of the underlying issue, it is not for us to gainsay its selection of remedies.

The Supreme Court further emphasized that a prior restraint is not per se unconstitutional, and that the New York Statute utilized to gain the injunction was “closely confined so as to preclude… licensing or censorship.” In addition, the Court held that the injunction was constitutional even though Kingsley Books was not afforded a jury trial before the Court granted the injunction because “the consequences of a judicial condemnation for obscenity under [The new York Statute] are not more restrictive of freedom of expression than the result of a conviction for a misdemeanor. Further, the provision for the seizure and destruction of the instrumentalities of ascertained wrong-doing is a resort to a legal remedy sanctioned by the long history of the Anglo-American law.”

The Kingsley Books case drew three separate dissenting opinions. Mr. Chief Justice Warren had a problem with any assessment of a book which did not consider the identities of the buyer and seller and the circumstances of the sale. Mr. Justice Douglas, with whom Mr. Justice Black concurred, objected to the temporary-injunction provision as “prior restraint and censorship at its worst.” Finally, Mr. Justice Brennan argued that a jury trial must constitutionally be available in any obscenity case, since a jury is peculiarly competent to apply the obscenity test from the required viewpoint of “the average person, applying contemporary community standards.”

But, the story doesn’t end there. Eugene Maletta, the owner of Pilgrim Press and the printer of Nights of Horror, was arrested on September 15, 1954, after he was turned in by a relative who read in the New World Telegram about the connection between Nights of Horror and the Brooklyn Thrill Killers. Later, as part of an investigation into “Pornography and its Effect on Juvenile Delinquency,” the United States Senate (led by Senator Kefauver, who famously questioned Bill Gaines in the 1954 comic book hearings) grilled Maletta and Edward Mishkin, a co-owner of Kingsley Books with alleged ties to the Gambino crime family, about Nights of Horror. In response, both Maletta and Mishkin pled the Fifth Amendment right against self incrimination. Mishkin was threatened with contempt (and papers were apparently drawn up), but the Senate never acted on the charge.

In the course of writing this article, I was able to get a copy of Nights of Horror, Volume 1, and Nights of Horror, Volume 15. I have definitely seen better and have certainly seen worse on the more easily accessible internet. The stories are the equivalent of an R-rated movie or a cable television show. For example, here are first two pages of the text from Volume 15 and the accompanying image (which is completely unrelated to the text and the story):

Nights of Horror is certainly not for children, but it would clearly be acceptable for adults. As a result, New York could have simply limited the books so that it could only be sold to adults. But they did not do this (probably because sales were already limited to adults). Instead, the New York Corporation Counsel sought and received an injunction, which permitted them to destroy every known copy of the book. In essence, they received a Court-mandated sanction to wipe Nights of Horror from the face of the earth as if it never existed so that adults and children would not be tainted. Don’t get me wrong, Nights of Horror was by no means well-written or sophisticated, but, with the benefit of hindsight and a modern view, I certainly wouldn’t agree with Judge Levy that they are “dirt for dirt” sake without any historical significance. The fact that the co-creator of Superman did the images makes the books historically relevant. Unfortunately, very few copies of the books remain, but what is left is revealing. As Stan Lee states, in his introduction to Secret Identity:

Some of the material in this book may seem shocking; some figured strongly in censorship investigations in Congress; but all of it will certainly give you pause as you consider the consequences that can ensue when a gifted man is forced to lend his talent to the most sordid of projects.

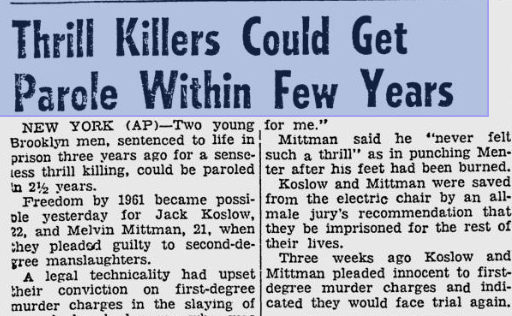

As an addendum to the story, it should be pointed out that the two convicted Thrill Killers, Koslow and Mittman, won their appeal and had to be retried. The Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court found (with 3-2 decision) that there were errors of fact and law that necessitated a new trial. Specifically, the Court found that the Thrill Killers did not kidnap Mentor and therefore could not have been guilty of murder in the first degree, committed in the course of the commission of the independent felony of kidnapping. Afterward, both teens pled guilty to second degree murder and received a sentence of 10 to 20 years and received credit for the four years they had served in jail. The pair was first eligible for parole in 1961. I couldn’t find out what happened to them after that. I will note that nearly every online story, article, book, magazine, and law review article I encountered in my research omits the retrial and reduced sentence and some even imply that the Brooklyn Thrill Killers are still in jail serving their life sentences.

As a further addendum, I should also point out what happened to the rest of the cast of this strange story.

In 1957, the Corporation Counsel of New York brought a second injunction against Kingsley Books. This time, the Corporation Counsel sought to destroy packages of photographs depicting a striptease. Once again, the case was assigned to Judge Levy. This time, however, the court determined that the photographs were not obscene in light of the Bill of Rights. The court stated, “Whatever I might say as to a number of these photographs being inartistic or inelegant, I hold that the prints in evidence — either singly or in a set — are not “obscene”, as that term has thus been authoritatively defined by our appellate courts.”

In response to a public backlash against the comics industry in general and as a result of publishers concerned about government regulation specifically, the comic book industry formed a self-regulatory body, which would impose and self-police a “code of ethics and standards” for the industry. On October 26, 1954, the comics industry, under the guise of the Code of the Comics Magazine Association of America, Inc., adopted the Comics Code Authority and began nearly 60 years of self censorship.

After the imposition of the Comics Code Authority, the New York State Joint Legislative Committee to Study the Publication of Comics moved its focus away from comics and more towards “girlie” magazines and paperback books. In 1956, the Committee changed its name to New York Joint Legislative Committee to Study the Publication and Dissemination of Objectionable and Obscene Materials.

Dr. Wertham, on the other hand, did not think the Comics Code alleviated the problem and in 1955 wrote, “At present, it is far safer for a mother to let her child have a comic book without a seal of approval that one with such a seal. If comic books, as the industry claim, are the folklore of today, then the codes are the fables. The problem is really simple. You either close down a house of prostitution or you leave it open.”

Dr. Wertham, on the other hand, did not think the Comics Code alleviated the problem and in 1955 wrote, “At present, it is far safer for a mother to let her child have a comic book without a seal of approval that one with such a seal. If comic books, as the industry claim, are the folklore of today, then the codes are the fables. The problem is really simple. You either close down a house of prostitution or you leave it open.”

In 1960, a 198-count indictment was prepared, calling Mishkin “the largest producer and purveyor of pornographic material in the U. S.” Mishkin was convicted in 1962 and sentenced to three years in prison and fined $12,000. The Supreme Court upheld the conviction in 1966.

In 1962, Harry Donenfeld fell at his home, injuring his head, which resulted in a lack of memory and speech. He never recovered and died at a care home in 1965.

In 1975, DC comics finally agreed to provide Joe Shuster, along with co-creator Jerry Siegel, a life-long pension of $25,000 each per year, along with fully paid medical benefits and a bonus each year (the pension was later increased to $80,000). More important to the creators was the fact that the pair once again would be credited as the creators of Superman in every known media that the character appeared. Joe Shuster died on July 30, 1992. His estate filed termination notices to DC Comics to reclaim Superman, and a California District Court has ruled that the 50% of the character will revert back to Joe Shuster’s estate in 2013.

As far as I know, similar termination notices were never filed to reclaim Joe’s interest in Nights of Horror.

Superman still fights a never-ending battle for truth and justice in the pages of DC Comics.

Today, the Brooklyn Thrill Killers have been largely forgotten. Still, the trial of the gang that made headlines during the late summer of 1954 provide a unique lens into popular fears and political responses to juvenile delinquency in the early 1950s. The connection between Wertham and Shuster can only make the lens that much more interesting.

Still, there is much to learn. In the 1950s, Nights of Terror was blamed for the Brooklyn Thrill Killers. In the much more recent past, The Matrix was blamed for Columbine; Grand Theft Auto was blamed for riots in the United Kingdom and murders in Asia, and, most recently, Batman was initially blamed for the tragedy in Aurora, Colorado. So, as the public cries for justice and protection, we have to be reminded that we shouldn’t sacrifice fundamental rights the Constitution to obtain them.

Given their visual nature, graphic novels and comic books are among the most-challenged books in libraries and schools. CBLDF is an official sponsor of Banned Books Week, which takes place September 30 – October 6, 2012. Please help support CBLDF’s defense of your right to read by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net/.

Superman is (c) DC Comics.