The case Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District is special for several reasons. First, Tinker is a landmark case that defines the constitutional rights of students in public schools. But more importantly, Tinker shows that people can make a difference in the world by standing up for what they believe. These people don’t need to be old, strong, or powerful — they just need to be committed. In fact, sometimes the world can be changed by the actions of two boys and a girl in their early teens. This is the story of three such people: John Tinker, 15 years old, his sister Mary Beth Tinker, 13 years old, and Christopher Echardt, 16 years old, all of whom decided to wear black armbands to protest a war they didn’t believe in. This action led to a landmark decision that created a rule to protect the free speech rights of students.

The case Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District is special for several reasons. First, Tinker is a landmark case that defines the constitutional rights of students in public schools. But more importantly, Tinker shows that people can make a difference in the world by standing up for what they believe. These people don’t need to be old, strong, or powerful — they just need to be committed. In fact, sometimes the world can be changed by the actions of two boys and a girl in their early teens. This is the story of three such people: John Tinker, 15 years old, his sister Mary Beth Tinker, 13 years old, and Christopher Echardt, 16 years old, all of whom decided to wear black armbands to protest a war they didn’t believe in. This action led to a landmark decision that created a rule to protect the free speech rights of students.

I should probably stop here and explain how wearing an armband can be considered “speech” at all, let alone “free speech.” Everyone knows that, with limited exceptions, the Constitution protects the communication of ideas through spoken or written words. That’s called “pure speech.” However, there is another type of protected speech, which is called “symbolic speech.” Symbolic speech is used to describe nonverbal gestures and actions that are meant to communicate a message, such as marching, wearing armbands, or even displaying or mutilating the U.S. flag. And while the Supreme Court has clearly held that symbolic speech is entitled to First Amendment protection, the scope and nature of that protection have varied.

Before we tell the story of Tinker, it is important to understand some background information about the Vietnam War, which was a prolonged conflict between nationalist forces attempting to unify the country of Vietnam under a communist government and the South Vietnamese (with the aid of the United States), who were attempting to prevent the spread of communism. In the early years of the war, the United States’ involvement was limited to sending advisers to assist the South Vietnamese in their fight against the North Vietnamese (which communist sympathizers in South Vietnam called the National Liberation Front, also known as the Viet Cong). However, when the North Vietnamese fired directly upon two U.S. ships in international waters on August 2 and 4, 1964, in the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, Congress responded with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. This resolution gave the President the authority to escalate U.S. involvement in Vietnam. President Lyndon Johnson used that authority to order the first U.S. ground troops to Vietnam in March 1965.

The U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War was not popular with everyone. On May 12, 1964, twelve young men in New York publicly burned their draft cards to protest the war. Later that year, Joan Baez led six hundred people in an antiwar demonstration in San Francisco. By the end of 1965, more than a thousand U.S. troops had died in battle, and the anti-war movement had significantly expanded to become a national and even global phenomenon, with anti-war protests held simultaneously in as many as 80 major cities around the US, London, Paris, and Rome, each drawing more than 100,000 protestors.

Meawhile, President Johnson was faced with the decision whether to escalate troop involvement. Some politicians insisted that the United States stay involved, while others resisted escalation. One of these Senators, Robert F. Kennedy, proposed a Christmas Truce be extended. A group of students in Des Moines, Iowa, heard out about Senator Kennedy’s proposal. On December 11, 1965, these students met at the home of Christopher Eckhardt (pictured left), a 16-year-old student at Theodore Roosevelt High School, to make plans to wear black armbands in support of the truce and to mourn the loss of soldiers in the war. However, On December 14, the principals of the Des Moines school system found out about the students’ plans and unanimously voted to adopt a policy that all students wearing armbands to school would be asked to remove them. If they refused, they would be suspended until they were willing to return without the armbands.

Meawhile, President Johnson was faced with the decision whether to escalate troop involvement. Some politicians insisted that the United States stay involved, while others resisted escalation. One of these Senators, Robert F. Kennedy, proposed a Christmas Truce be extended. A group of students in Des Moines, Iowa, heard out about Senator Kennedy’s proposal. On December 11, 1965, these students met at the home of Christopher Eckhardt (pictured left), a 16-year-old student at Theodore Roosevelt High School, to make plans to wear black armbands in support of the truce and to mourn the loss of soldiers in the war. However, On December 14, the principals of the Des Moines school system found out about the students’ plans and unanimously voted to adopt a policy that all students wearing armbands to school would be asked to remove them. If they refused, they would be suspended until they were willing to return without the armbands.

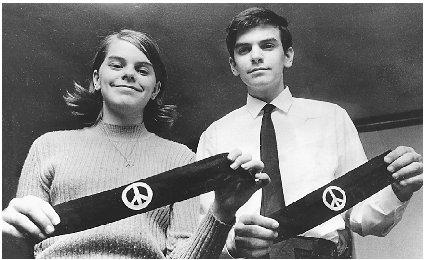

Almost all of the students, fearing suspension, backed out the protest. In the end, it was estimated that more than two dozen students wore black armbands (with peace symbols on them) to Des Moines high, middle, and elementary schools. John Johnson writes, in his book, The Struggle for Student Rights that, “[u]ltimately, only five Des Moines secondary-school students were singled out for discipline for wearing armbands in December 1965: Christopher Eckhardt, John and Mary Beth Tinker (pictured below), Roosevelt sophomore Christine Singer, and Roosevelt senior Bruce Clark.” Each student was asked to remove the armband, and when they refused, they were suspended until after New Year’s Day.

Christopher Eckhardt told Education for Freedom that several students threatened him,

I wore the black armband over a camel-colored jacket. The captain of the football team attempted to rip it off. I turned myself in to the principal’s office where the vice principal asked if ‘I wanted a busted nose.’ He said seniors wouldn’t like the armband. Tears welled up in my eyes because I was afraid of violence. He called my mom to get her to ask me to take the armband off. Then he called a school counselor in. The counselor asked if I wanted to go to college, and said that colleges didn’t accept protesters. She said I would probably need to look for a new high school if I didn’t take the armband off.

Mary Tinker describes her decision in “What a Black Armband Means, Forty Years Later” as follows:

Some students in Des Moines decided to wear black armbands to support him, and wrote an article about it in their school newspaper. The principals saw the article and ruled that any students who tried to wear black armbands to school would be suspended.

After that, we weren’t sure what to do. We’d learned about the Bill of Rights and the First Amendment in school, and we felt free speech should apply to kids, too. We also had the examples of brave people standing up against dogs and firehoses to fight racism. In the end, we decided to go ahead and wear the armbands, and some of us were suspended.

More details were provided by their counsel at the oral argument before the Supreme Court:

Mr. Eckhardt went to school, had the armband on, but knowing of the policy against the wearing of the armbands . . . he went quite immediately to the office of the principal and said I’m wearing the armband. I know it is in violation of the school policy. The principal carried out the dictates of the policy which were to tell the student to remove it. The student said that he could not in good conscience remove the armband, that he thought he had a right to wear it. The student’s mother was called and she supported her son in the activity and then young Mr. Eckhardt was suspended.

Mary Beth Tinker also wore her armband on that first day. However, she wore it throughout the entire morning without any incident related to it that in any way disrupted the school or distracted. She wore it at lunch and she wore it, where there was, by the way, some conversation between herself and other students in the lunch room about why she was wearing the armband and whether or not she should be wearing it and then wore it into the first class in the afternoon and it was in the afternoon that she was called to the office and the procedure was followed for contacting her parents, apparently asking her to remove it and she did remove the armband and then returned to class. However, in spite of the fact that she had removed the armband and returned, and was returned to class, she was later called out of class and suspended…

[O]n the first day John Tinker did not wear the armband to school… [O]n the next day, Friday, John Tinker wore an armband to school, wore it throughout the morning hours without any toward incident, without any substantial or material disruption to the school, wore it at lunch where there was again some discussion about it in a period that’s generally free and open for discussion among students and then wore it into the first class in the afternoon where he was suspended.

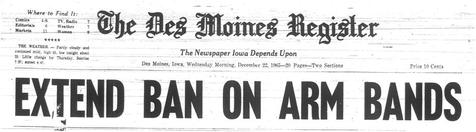

The decision to suspend the students was hotly debated by the school board, which ultimately voted 5-2 to uphold the policy. The Des Moines Register and the New York Times carried stories about the armband suspensions.

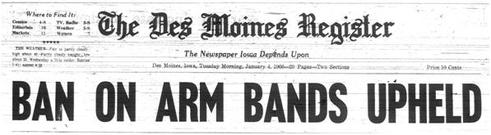

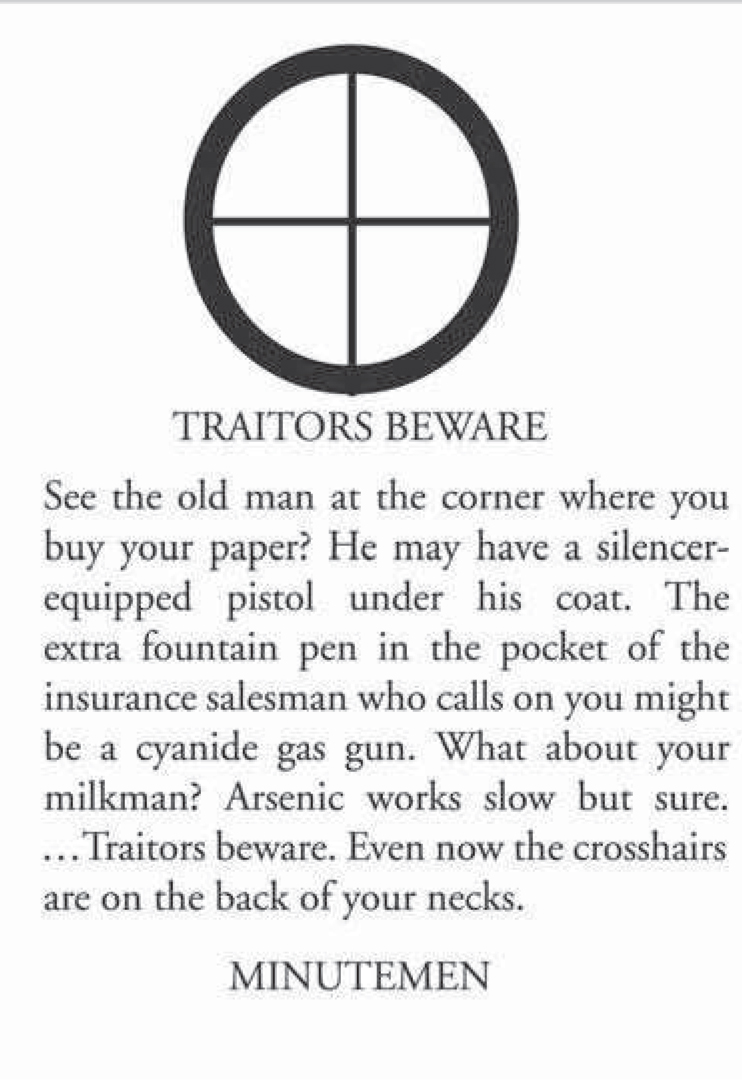

Armbands were a heated topic in the community. Mary Beth Tinker remembers:

[W]e’d gotten a lot of threats. A man who had a radio talk show threatened my father on the air. Red paint was thrown on our house. A woman called on the phone, asked for me by name, and then said, ‘I’m going to kill you!’

As a further example, here are some letters received by the Tinker family:

The children returned to school after January 1, 1966, exchanging their black armbands for black clothing. And while most of the other students did not challenge the law, the Iowa Civil Liberties Union approached the Eckhardt and Tinker families suggesting they take legal action, and the ACLU agreed to help the families with their lawsuit. On March 14, 1966, Dan Johnston of the Iowa Civil Liberties Union (pictured right) filed a complaint on behalf of Christopher Eckhardt and John and Mary Beth Tinker, as well as their fathers as “next friends” in the U. S. District Court of the Southern District of Iowa. This suit asked the court for a money damages and an injunction to restrain school officials from enforcing their armband policy. Years later, Dan Johnston admitted that he thought this “was an easy case” that it should have been won at the District Court level. He admitted to David L. Hudson, Jr., from the First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University, in a 1999 interview that “[I]f we had won, this case could never have become such a landmark decision.”

The children returned to school after January 1, 1966, exchanging their black armbands for black clothing. And while most of the other students did not challenge the law, the Iowa Civil Liberties Union approached the Eckhardt and Tinker families suggesting they take legal action, and the ACLU agreed to help the families with their lawsuit. On March 14, 1966, Dan Johnston of the Iowa Civil Liberties Union (pictured right) filed a complaint on behalf of Christopher Eckhardt and John and Mary Beth Tinker, as well as their fathers as “next friends” in the U. S. District Court of the Southern District of Iowa. This suit asked the court for a money damages and an injunction to restrain school officials from enforcing their armband policy. Years later, Dan Johnston admitted that he thought this “was an easy case” that it should have been won at the District Court level. He admitted to David L. Hudson, Jr., from the First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University, in a 1999 interview that “[I]f we had won, this case could never have become such a landmark decision.”

There was even antagonism between the litigants and the lawyers. Perry Zirkel points out, in an article “The 30th Anniversary of Tinker,” that Allan Herrick “was a leader of the First Methodist Church in downtown Des Moines as well as the lead attorney for the district, [and] had little patience with Leonard Tinker because Tinker was a Methodist minister without a church.” Herrick’s law clerk at the time, Edgar Bittle, admitted, “There was some real antagonism among these folks. Herrick was also influenced by his own status as a veteran of two wars. . . . I think that some of Allan’s conduct was attributable to age, which for him was probably 65 or 70 at that point.” Johnston added, “[Herrick] He was clearly very emotionally superpatriotic and anti-Communist. At the deposition of Leonard Tinker AI Herrick’s conduct was such that I either walked out or threatened to walk out at one point. . . . He was just abusive. . . . And for Herrick to be as abusive as he was I think was counterproductive to his case and unfair to my clients.”

An evidentiary hearing was held July 25-26, 1966, before Judge Roy Stephenson. As part of his article, Perry Zirkel interviewed Johnston, who described the hearing as follows:

The hearing lasted no more than a couple of days. It was not a long trial. One of the tensions in our camp was that the families really wanted to make the trial a kind of forum for their antiwar views, and I told them that I didn’t think that was proper and that’s not what I signed on for. This was a free speech First Amendment case, and it didn’t make any difference what views they were trying to espouse by wearing the armbands. The evidence and the arguments would be limited to the free speech issue alone.

On September 1, 1966, The District Court entered a memorandum opinion dismissing the complaint. Although Judge Stephenson recognized the children’s First Amendment right to free speech, the court refused to issue an injunction upholding the constitutionality of the schools’ actions based on the reasoning that the student’s actions presented a disturbance of school discipline and could disrupt learning. The Court stated:

Officials of the defendant school district have the responsibility for maintaining a scholarly, disciplined atmosphere within the classroom. These officials not only have a right, they have an obligation to prevent anything which might be disruptive of such an atmosphere. Unless the actions of school officials in this connection are unreasonable, the Courts should not interfere.

Johnston appealed and the case was heard by U. S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit. Johnston described the arguments to Zirkel as follows:

We went there twice. First, we argued before a three-judge panel. Then we got a notice that they wanted us back down to argue in front of all eight judges. That decision split 4 to 4, so there are no written opinions with any statement of facts or law in them, because the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals wasn’t able to reach a decision. The effect of the split decision was to affirm Judge Stephenson’s opinion.

On November 3, 1967, The 8th Circuit affirmed the decision simply stating:

This is an appeal from a judgment entered September 1, 1966, by the United States District Court for the Southern District of Iowa, Central Division, dismissing plaintiffs’ complaint, based upon 42 U.S.C.A. § 1983, seeking an injunction and nominal damages against defendants, the Des Moines Independent Community School District, the individual members of its Board of Directors, its superintendent and various principals and teachers thereof, for suspending plaintiffs from school for wearing arm bands protesting the Viet Nam war, in violation of a school regulation promulgated by administrative officials of the School District proscribing the wearing of such arm bands. 258 F. Supp. 971. Following argument before a regular panel of this court, the case was reargued and submitted to the court en banc.

The judgment below is affirmed by an equally divided court.

Johnston then petitioned the Supreme Court for certiairi, which was granted.

The issue before the Supreme Court was whether the prohibition against the wearing of armbands in public schools as a form of symbolic protest violated the First Amendment’s freedom of speech protections. Oral argument was held on November 12, 1968 (a recording of the argument can be found at http://www.oyez.org/cases/1960-1969/1968/1968_21 ).

In the oral argument, Allan Herrick, who represented the Des Moines Independent School District, summarized his position as follows:

[T]he right of freedom of speech or the right of demonstration in the schoolroom and on the school premises must be weighed against the right of the school administration to make a decision which the administration, in good faith, believed and its discretion was reasonable to preserve order and to avoid disturbance and disruption in the schoolroom….

[I]t was a matter of the explosive situation that existed in the Des Moines schools at the time the regulation was adopted. …A former student of one of our high schools was killed in Vietnam. Some of his friends are still in school. It was felt that if any kind of a demonstration existed, it might evolve into something which would be difficult to control.

In response, Justice Marshall asked, “Do we have a city in this country that hasn’t had someone killed in Vietnam?” Herrick responded, “No, I think not your honor. But, I don’t think it would be an explosive situation in most, in most cases, but if someone is going to appear in court with an armband here protesting the thing, then it could be explosive. That’s the situation we find here….”

During his argument, Johnston summarized the reasoning of the teens to show the nature of the symbolic speech:

The conduct of the students essentially was this: that at Christmas time in 1965, they decided that they would wear small black armbands to express certain views which they had in regard to the war in Vietnam. Specifically, the views were that they mourned the dead of both sides, both civilian and military, in that war and they supported the proposal that had been made by United States Senator Robert Kennedy that the truce which had been proposed for that war over the Christmas period be made an open ended or indefinite truce…

Johnston then explained, in response to questioning by the Justices, why the conduct wasn’t disruptive.

Justice White: Why did they wear the armbands in the class, to express that message?

Johnston: To express the message.

White: And to understand it?

Johnston: And to understand it.

White: And to absorb that message?

Johnston: And to absorb the message.

White: …while they are studying arithmetic or mathematics, they are supposed to be taking in this message about Vietnam?

Johnston: …the message the students chose in this particular incident was specifically designed in such a way that it would not cause that kind of disruption. None of the teachers testified at the hearing in the district court….

White: Physically it wouldn’t make a noise. It wouldn’t cause a commotion, but don’t you think that it would cause some people to direct their attention to the armband and the Vietnam War and think about that rather than what they were… supposed to be thinking about in the classroom?

David Eckhardt remembered sitting in the Courtroom. In 1999, He told David Hudson, Jr. that he knew he and the Tinkers would win the case when Justice Thurgood Marshall asked the attorney for the school board: “Seven out of eighteen thousand, and the school board was afraid that seven students wearing armbands would disrupt eighteen thousand. Am I correct?”

Mary Beth Tinker, was not as confident as she sat in the Court and watched. She told ABC News

I didn’t think we’d win. I was happy, but I had all the emotions of a young teenager who was more worried about having a run in my stocking. I didn’t know the historical importance of the issue.

John Tinker did not see the argument. He flew stand by on flight to Washington, DC, and never made to the courthouse.

On February 24, 1969, the Supreme Court reversed the lower courts in a 7-2 decision, and ruled in favor of the students. In doing so, the Court enunciated a test that is still applied today in determining whether a school’s disciplinary actions violate students’ First Amendment rights

Justice Fortis wrote the majority opinion and described the issue before the Court. First, he stressed the importance of First Amendment rights:

It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate. This has been the unmistakable holding of this Court for almost 50 years.

But, he also acknowledged:

On the other hand, the Court has repeatedly emphasized the need for affirming the comprehensive authority of the States and of school officials, consistent with fundamental constitutional safeguards, to prescribe and control conduct in the schools.

Thus, the Court concluded, “Our problem lies in the area where students in the exercise of First Amendment rights collide with the rules of the school authorities.”

To resolve this conflict, the Court looked at the effect of the speech in light of the prohibition. In upholding the students’ First Amendment rights, the Court found:

The school officials banned and sought to punish petitioners for a silent, passive expression of opinion, unaccompanied by any disorder or disturbance on the part of petitioners [the students]. There is here no evidence whatever of petitioners’ [the students’] interference, actual or nascent, with the schools’ work or of collision with the rights of other students to be secure and to be let alone. Accordingly, this case does not concern speech or action that intrudes upon the work of the schools or the rights of other students.

Addressing the concerns raised by the District Court, the Majority wrote:

The District Court concluded that the action of the school authorities was reasonable because it was based upon their fear of a disturbance from the wearing of the armbands. But, in our system, undifferentiated fear or apprehension of disturbance is not enough to overcome the right to freedom of expression. Any departure from absolute regimentation may cause trouble. Any variation from the majority’s opinion may inspire fear. Any word spoken, in class, in the lunchroom, or on the campus, that deviates from the views of another person may start an argument or cause a disturbance. But our Constitution says we must take this risk, and our history says that it is this sort of hazardous freedom — this kind of openness — that is the basis of our national strength and of the independence and vigor of Americans who grow up and live in this relatively permissive, often disputatious, society.

In short, the Court concluded that the wearing of armbands was not actually or potentially disruptive conduct. Instead, the Court concluded that the action was very similar to pure speech and is entitled to First Amendment Protection. Of course, the Supreme Court also was careful to state that these First Amendment rights must be applied carefully “in light of the special characteristics of the school environment.”

So, where are the litigants today? In 2007, ABC news did a story entitled, “Now Middle-Aged, Student Protesters Echo Triumphs and Casualties of the 1960s,” they reported,

Today, Mary Beth Tinker is a nurse, caring for her ailing mother. John Tinker runs a liberal-leaning Web site, and Eckhardt lives in a homeless shelter, after he was convicted of a felony he claims he never committed. [Eckhardt was charged with exploitation of the elderly for which he served four years in prison].

To update this story, I did some additional research and found that Chris Eckhardt died in December of last year. Mary Beth Tinker told Hudson, “He spoke up for the First Amendment, but also used it in his life to promote justice, Most recently, he published a book on the rights of psychiatric patients. He was also a strong advocate for the rights of prisoners, and for gay rights.” Mary Beth Tinker gives talks with students about their First Amendment rights and the importance of speaking out. John Tinker runs a current events website that advocates for democracy around the world. Dan Johnston, their attorney, works in private practice and is Of Counsel at Glazebrook & Moe, LLP. He previously served as Polk County Attorney and as an Iowa General Assembly Member. Allan Herrick was never pleased with the decision. His daughter stated, in a 1995 interview with Leigh Wolfe-Dawson that 26 years later her late father “grieved over the decision” when he looked back at the events.

This is a landmark decision because it establishes that students have the same rights as adults and should be taken seriously. Middle and high school students are at an important stage of their social and intellectual development, a stage in which they are shaping their personalities, learning how to behave in society, and becoming good citizens. If authorities fail to respect or protect student’s Constitutional rights in school, then there is a pretty good chance that these students will be less likely to respect or protect those rights when they grow up and graduate.

This could perhaps be best expressed in Mary Tinker’s own words:

I was scared the day I wore that armband to school, but I knew I had to speak up. The world seemed upside-down, but my friends and I had courageous role models to show us how to stand up for what we believed. If you look around, there are many others like that, whether in your home, your school, your neighborhood, your town or even across the world. You can join them to change the world, and when you do your life will be meaningful and very interesting. It certainly has been for me!

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net