The First Amendment guarantees our right to free speech, but there are certain types of speech that fall outside of its protection. Obscenity is a type of unprotected speech, but what exactly is considered obscene in the eyes of the law? Courts have struggled to sort out this murky definition, and the landmark 1973 decision in Miller v. California has become the go to case in defining obscenity.

Marvin Miller owned and operated a mail order pornography business based out of California. To promote his products, Miller assembled brochures that featured graphic pictures of some of his products. In 1971, he assembled a brochure that advertised the books Intercourse, Man-Woman, Sex Orgies Illustrated, and An Illustrated History of Pornography and the movie Marital Intercourse. He mass mailed the brochures, and five of the unsolicited brochures found their way to a restaurant in Newport Beach, California. Despite not having requested the brochures, the restaurant owner and his mother decided to open the envelopes. They were offended by the graphic pictures that they found in the brochures, and reported them to the police. Subsequently, Miller was charged and convicted with violating a California statute for “knowingly distributing obscene matter.” Miller’s conviction was upheld by the appellate court, and the case made its way to the Supreme Court in 1973.

In examining Miller v. California we must first take a look at earlier Supreme Court cases that had attempted to define obscenity. The standard for determining obscenity was set in 1957 in Roth v. United States. In Roth, a man named Samuel Roth had a literary business and sold a publication called American Aphrodite, which contained both erotic literature and nude photographs. Like Miller, he was convicted for advertising obscene material. The Roth case established that obscenity as a category was not protected by the First Amendment. It then attempted to define exactly what obscenity was. Roth defined obscene matter as not having any redeeming social importance and determined that material is obscene, when taken as a whole, if it appeals to the prurient interests of the average person when applying contemporary community standards. In other words, to determine if something is obscene, you must look at the entire context of the publication, not just an excerpt of the contentious part. Also, it must be judged based on what the average person might think about it.

In examining Miller v. California we must first take a look at earlier Supreme Court cases that had attempted to define obscenity. The standard for determining obscenity was set in 1957 in Roth v. United States. In Roth, a man named Samuel Roth had a literary business and sold a publication called American Aphrodite, which contained both erotic literature and nude photographs. Like Miller, he was convicted for advertising obscene material. The Roth case established that obscenity as a category was not protected by the First Amendment. It then attempted to define exactly what obscenity was. Roth defined obscene matter as not having any redeeming social importance and determined that material is obscene, when taken as a whole, if it appeals to the prurient interests of the average person when applying contemporary community standards. In other words, to determine if something is obscene, you must look at the entire context of the publication, not just an excerpt of the contentious part. Also, it must be judged based on what the average person might think about it.

In Memoirs v. Massachusetts (1966), the Court was not content with the standard set in Roth and tried to revise it, but their attempts were in vain. The Memoirs case was about a book entitled The Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (aka Fanny Hill) by John Cleland. Many raised concerns over the book’s content because it included scenes of sodomy and masturbation, which caused quite a ruckus in 1960s courtrooms. In Memoirs, the Court rejected the standard set by Roth and determined that material was obscene if it was both patently offensive AND it was utterly without social value. Under this standard, if there was any question that material might have some social value at all, then it could not be considered obscene. Ultimately, due to the fact that the book was artistic literary expression despite including some graphic content, it could not be proven that Fanny Hill had absolutely no redeeming social value and was therefore not considered obscene.

In Memoirs v. Massachusetts (1966), the Court was not content with the standard set in Roth and tried to revise it, but their attempts were in vain. The Memoirs case was about a book entitled The Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (aka Fanny Hill) by John Cleland. Many raised concerns over the book’s content because it included scenes of sodomy and masturbation, which caused quite a ruckus in 1960s courtrooms. In Memoirs, the Court rejected the standard set by Roth and determined that material was obscene if it was both patently offensive AND it was utterly without social value. Under this standard, if there was any question that material might have some social value at all, then it could not be considered obscene. Ultimately, due to the fact that the book was artistic literary expression despite including some graphic content, it could not be proven that Fanny Hill had absolutely no redeeming social value and was therefore not considered obscene.

Miller’s defense tried to base his appeal on the loose standards in Memoirs but failed. Regardless, the Supreme Court recognized that the appellate court decision against Miller was based on outdated standards of determining what was considered obscene and vacated Miller’s conviction. The Supreme Court decision led to a new test for obscenity that is still in use today.

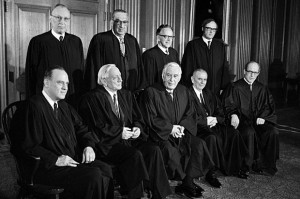

The Miller v. California decision held the following:

- Obscene material is not protected by the First Amendment. Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 , reaffirmed. A work may be subject to state regulation where that work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest in sex; portrays, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law; and, taken as a whole, does not have serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

- The basic guidelines for the trier of fact must be: (a) whether “the average person, applying contemporary community standards” would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest, Roth, supra, at 489, (b) whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law, and (c) whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. If a state obscenity law is thus limited, First Amendment values are adequately protected by ultimate independent appellate review of constitutional claims when necessary.

- The test of “utterly without redeeming social value” articulated in Memoirs, supra, is rejected as a constitutional standard.

- The jury may measure the essentially factual issues of prurient appeal and patent offensiveness by the standard that prevails in the forum community, and need not employ a “national standard.”

In point 1, the Supreme Court reiterated that obscene material was not protected by the First Amendment as determined in Roth v. United States. In point 3, the Supreme Court rejected the definition of obscene material set in Memoirs v. Massachusetts. With point 4, the Court recognized that a jury in obscenity cases is held to local standards, not a national standard.

Point 2 became what is known today as the three-prong Miller Test for obscenity. The first part of the Miller Test — “the average person applying contemporary community standards would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interests” — emphasized that different parts of the country might have different opinions on obscene materials. For instance, material that might not offend your average New Yorker may be offensive to someone living in Oklahoma. The court recognized that communities might have differing point of views, and it wouldn’t fulfill the purpose of the test to impose a national standard. It is also important to note that the entire work is to be considered in its entirety. Even if an excerpt is deemed obscene, unless the entire work is determined to be obscene, the work is still protected by the First Amendment.

The second part of the Miller Test required that “the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by state law.” This second prong also focuses on locality. As with matters appealing to prurient interests, some things may be found patently offensive in one state but not necessarily in the other. Imposing a national standard would be unrealistic.

The third and final prong of the Miller Test required that “the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.” Here, the Court was reworking the former standard of being “utterly without redeeming social value.” The Court found this standard to be far too strict — so strict, in fact, that it was virtually impossible to prove in a criminal proceeding. (If you think about it, how can you possibly prove with any certainty that something has zero value whatsoever?) There is always an argument to be made in one way or another, and the courts recognized this difficulty. With this prong of the Miller Test, it would only need to be proven that the work lacks literary, artistic, political or scientific value, not any sort of value whatsoever. (It should be noted that the Court did not clearly define who made this determination, an issue that was resolved in 1987 with Pope v. Illinois.)

After struggling for years to come to a consensus on what the law could actually consider to be obscene, the standard that was set in Miller v. California still stands today. Although this case didn’t directly involve comic books, it is still an extremely important decision for CBLDF’s own legal work. Comic books are frequently labeled obscene by those who would censor them, a label that clearly does not hold up against the Miller Test.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Eric Margolis is a 3L at St. John’s Law School who wishes to pursue a career in Entertainment / Intellectual Property law.