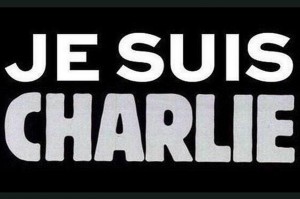

American political satirist and cartoonist Garry Trudeau is no stranger to inciting controversy with his work, and in his recent article published in The Atlantic, he invited further controversy with inflammatory comments equating the editorial decisions at the Charlie Hebdo office to hate speech and what he describes as a rising trend of “free-speech fanaticism.”

American political satirist and cartoonist Garry Trudeau is no stranger to inciting controversy with his work, and in his recent article published in The Atlantic, he invited further controversy with inflammatory comments equating the editorial decisions at the Charlie Hebdo office to hate speech and what he describes as a rising trend of “free-speech fanaticism.”

Entitled “The Abuse of Satire,” Trudeau breaks down in his article what he sees as a growing symptom of satire and free speech abuse in today’s modern age. According to Trudeau, cartoonists and editorial staff are more readily incorporating subject matter into their work that would be perceived as “punching down.” Traditional satire, Trudeau argues, has always been the opposite: “Traditionally, satire has comforted the afflicted while afflicting the comfortable. Satire punches up, against authority of all kinds, the little guy against the powerful.”

To “punch down” and use the shield of free speech for protection, according to Trudeau, is to target those who do not have the appropriate means to respond. Trudeau argues that to attack “a powerless, disenfranchised minority with crude, vulgar drawings closer to graffiti than cartoons” is to invite and incite violence. For Trudeau, there is a proverbial “red line” in satire, and he contends that in recent cases around the world, cartoonists have gotten bolder and bolder in seeing how close they can come to crossing that line before they actually breach the threshold — a threshold that in Charlie Hebdo‘s case meant violent retaliatory action against cartoonists and staff of the paper. Trudeau claims these cartoonists are not drawing “to entertain or to enlighten or to challenge authority” but to “provoke,” and for Trudeau this can represent a dangerous position in which what one person defends free speech can quickly morph into hate speech and free speech fanaticism:

What free speech absolutists have failed to acknowledge is that because one has the right to offend a group does not mean that one must. Or that that group gives up the right to be outraged. They’re allowed to feel pain. Freedom should always be discussed within the context of responsibility. At some point free expression absolutism becomes childish and unserious. It becomes its own kind of fanaticism.

Reactions to Trudeau’s comments have been collecting on the internet since the original article was posted, from some columnists describing Trudeau as a victim-blaming coward, who is afforded his ability to make these statements from his position of comfort, to a follow-up article in The Atlantic in which contributor David Frum explains that the situations that Trudeau describes are not nearly as black-and-white. At what point does a cartoonist know if they are punching up or punching down? If they are attacking a “privileged” group entitled to criticism or one of the “disenfranchised” who should be being defended?

All this being said, though, a majority of the backlash that Trudeau’s article has brought forth has been backlash on Trudeau and his own personal position as a cartoonist — a cartoonist who has himself been censored countless times for his own cartoons on controversial topics.

Upon first reading Trudeau’s Atlantic article, a natural impulse for free speech advocates is to feel outrage and to criticize the author for what appears to be comments emerging from a position of privilege, but at the core of Trudeau’s argument, there is a sentiment that should be recognized as we continue to move into a turbulent future in which the digital age has blurred geographical — and in many ways political and ideological — boundaries, making it both easier and riskier to skirt the proverbial red line.

At the core of Trudeau’s argument is the statement that when exercising free speech, one must always be conscious of the effects that his or her work might bring about. This is not to say that one should censor themselves. Perhaps Trudeau, in being the victim of censorship himself, has been jaded and his brusque wording is simply unveiling a personal sentiment as a warning to future generations of cartoonist to protect themselves and their work. No, it is as Neil Gaiman stated in his recent interview with CBLDF Executive Director Charles Brownstein for CBLDF Defender that in a healthy society we should be initiating hard conversations, but we should do it with the intent for nonviolent discourse:

[In a healthy society] you can argue back. You can say, “This comic that you’ve done with these people being murdered, I find it offensive, and this is why I find it offensive. I would like you not to do comics like this. This is why what you do upsets me and could upset other people.” You are so in your right to do that. I encourage you to do that! If you thought Charlie Hebdo was wrong, you could write them letters. Better still, you could start your own magazine, in which you can parody everything, including the people who do Charlie Hebdo.

I’m all for that. But what I’m not for is murder. What I’m not for is terror. What I’m not for is making people too scared to be controversial. Too scared to have opinions. Too scared of uttering, of offending, to speak. Because at that — the moment that people are too scared to speak you no longer have a free society. And I worry that we can find ourselves heading that way.

Trudeau’s words are an opinion influenced by his personal experiences as a cartoonist and as someone who has witnessed a lot of change and censorship in the cartooning world across decades, an opinion that Trudeau is within his rights to express. The responses to his article only demonstrate further the increasingly turbulent views the global community holds with regard to how one can and should proceed with freely expressing themselves. We don’t want government or community imposed censorship, we don’t want self-censorship, and we certainly don’t want violence perpetrated in opposition to or even in the name of free speech. What we need is healthy conversation and a clear mindset that enables conversation and does not lead to victim-blaming — even if the victim is in a perceived position of security.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Caitlin McCabe is an independent comics scholar who loves a good pre-code horror comic and the opportunity to spread her knowledge of the industry to those looking for a great story!