In the past few months we’ve noticed an uptick in a different kind of censorship from what we usually see. Namely, a few schools across the country have assigned their students to read texts that were first edited by hand: words blacked out with marker and modified from what the author wrote.

In the past few months we’ve noticed an uptick in a different kind of censorship from what we usually see. Namely, a few schools across the country have assigned their students to read texts that were first edited by hand: words blacked out with marker and modified from what the author wrote.

Unlike the more familiar cases involving challenges, review committees, and school board meetings that happen in public for all to see, these instances of unauthorized editing are more insidious. On the surface, it appears that the students are reading complex, potentially controversial texts; in reality, though, the texts have been pre-sanitized so as to avoid even the possibility of a public challenge. Not only does this practice rob the students of a well-rounded education, but it also violates both the First Amendment and U.S. copyright laws designed to protect authors’ creations from tampering.

The first recent instance of unauthorized editing by a school came to light in September at Nashville Prep, a publicly funded charter school serving grades 5-8. At the beginning of the school year, seventh grade students had been assigned to read David Benioff’s book City of Thieves. One parent challenged the book due to language found in the intact version, but the school’s defense was rather unique:

[E]very scholar has received a redacted version of the book… We changed scenes involving ‘sex’ to scenes involving ‘kissing.’ We changed curse words like ‘s**t’ to ‘poop.’ We also redacted whole sections that involved mature scenes.

In response to this brazen censorship, members of the National Coalition Against Censorship’s Kids’ Right to Read Project, including CBLDF, sent a letter to the company that runs the publicly funded school explaining why the practice is not acceptable:

Expurgating a book is a particularly disturbing form of censorship since it not only suppresses specific content deemed ‘objectionable,’ but also does violence to the work as a whole by removing material that the author thought integral. It is a kind of literary fraud perpetrated on an unsuspecting audience.

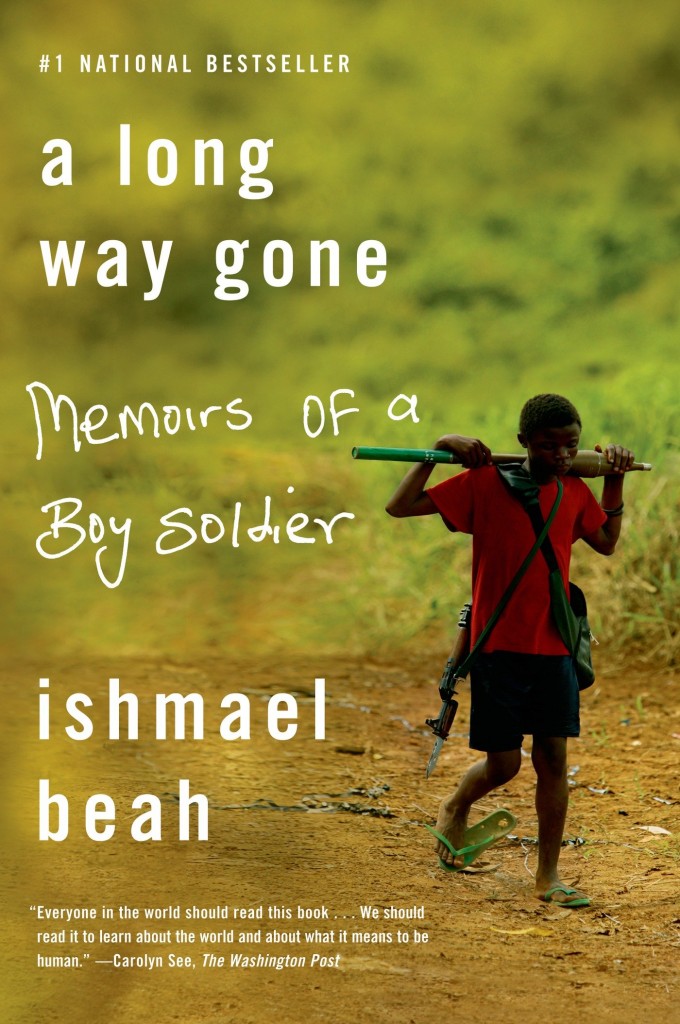

Last week, we learned of another instance of unauthorized editing that may seem less drastic, but is equally insulting to the students and the author, who in this case was writing his own true story. High school students in Richmond, Missouri, were assigned to read Ishmael Beah’s A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier. Originally from Sierra Leone, Beah was forced to join the army at the age of 13 after being separated from his family in the chaos of the country’s civil war. After three years of fighting alongside other minors, he was rescued and eventually made his way to the United States, where he still lives today.

Rather amazingly for a memoir with such intense subject matter, A Long Way Gone contains exactly one utterance of the word “fuck.” At Richmond High School the book has been assigned in years past with that one word blacked out in every copy given to students. While that may sound like a minor offense in a 230-page book, apparently English teacher Katie Rold saw the irony of her students being “protected” from one word that most of them no doubt encounter from time to time outside of class, but allowed to read a real-life horror story about children who were kidnapped, kept in a drug-induced haze, and trained to kill.

This year, Rold asked RHS principal John Parker if students could read the book unredacted. Parker referred the question to school board members, who read and praised the book but still unanimously decided that the single instance of “fuck” — used as an interjection, not a verb — must remain covered.

To be sure, this sort of custom censorship is nothing new. Some librarians and educators through the years famously painted on diapers or shorts to cover the fleeting frontal nudity of Mickey in Maurice Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen, although the practice was probably never as widespread as the media and Sendak himself believed. More recently in 2011, the small publisher NewSouth Books released a pre-censored omnibus edition of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn which “eliminate[s] the pejorative racial labels that Twain employed in his effort to write realistically about social attitudes of the 1840s” — never mind that doing so also eliminates much of the impact of his criticism of racism and the institution of slavery.

When schools present students with censored texts, they do a disservice not only to the students and teachers who must read and teach around redacted or modified words, but to society. In attempting to “protect” students — or more likely, to simply avoid complaints from parents — they produce young adults who don’t know what to do when faced with literature that makes them mildly uncomfortable. We’ve seen the results this year at a number of post-secondary institutions: Crafton Hills College, where a student and her parents challenged four graphic novels; Duke University, where some students publicly proclaimed their refusal to read the summer reading selection Fun Home; and the University of North Carolina, where a freshman student decided that a course called ‘Literature of 9/11’ was offensive and anti-American — even though he didn’t take the class himself.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.