For many Americans, the criminal offense of sedition–that is, criticism of the government–probably conjures up the notorious but short-lived Sedition Act of 1798, which played an important role in the election of 1800 but was allowed to expire the following year. But for millions of people in other former British colonies across the world, this vestige of English Common Law lives on as a constant threat to freedom of expression. Despite hard-won independence in countries and localities such as Singapore, Malaysia, India, Uganda, Tanzania, and Zambia, their new governments have often found the Crown-implemented Sedition Acts too irresistible to abandon.

We were reminded of this once again when Singapore cartoonist Leslie Chew recently criticized the city-state’s politically motivated enforcement of its own Sedition Act. In response to the police questioning of two people accused of making political posts on Facebook on the day before an election, when most political speech is prohibited by law, Chew recalled his own arrest on sedition charges three years ago:

In March 2013, someone filed a police report over one of my cartoons and just because of that, the police had me arrested under sedition, raided my parent’s home, seized all PCs including my dad’s, seized my phone and all data storage devices, thrown me into their stinky cell for 2 days, handcuffed me like a criminal, interrogated me for over 30 hours with handcuffs on, confiscated my passport and put me under island arrest for 3 months, forbidding me from returning to my home in Malaysia, made me report for police bail countless times, before they discovered that they cannot charge me with sedition and quietly drop the charge.

Police held on to Chew’s computers, phone, and digital storage devices throughout the fruitless three-month investigation, disrupting his work as he was unable to access saved files. When authorities finally realized (or admitted) that his cartoons did not qualify as seditious after all, they returned his property and his passport, but offered no apology or explanation for putting his entire life on hold for so long. Frustrated to see the same pattern repeated with the recent questioning of the two Facebook posters, Chew addressed voters who have kept the authoritarian People’s Action Party (PAP) in power for decades:

I can only hope that the same happens to you and your family members one day soon too. Perhaps only then will you fully appreciate what many innocent people have unjustly being made to go through due to your collective decision.

And when it does, you have my full congratulation because you do fully deserve it since you voted for it. I didn’t.

PAP ultimately has British colonial powers to thank for the legal fig leaf of the Sedition Act, which allows the trampling of civil rights to proceed unchecked. Even the UK itself had a Sedition Act until 2009, although no one had been charged under it since the 1970s. One of the main reasons it was finally repealed at that late date was that its continued existence in the UK “had been used by other countries to justify retaining the law,” according to a resource from the Media Legal Defence Initiative. British sedition laws in one form or another had existed as early as 1275, but a chastened Parliamentary Under Secretary of State at the Ministry of Justice noted that things had changed with the advent of modern democracy:

Sedition and seditious and defamatory libel [which were repealed at the same time] are arcane offences – from a bygone era when freedom of expression wasn’t seen as the right it is today. Freedom of speech is now seen as the touchstone of democracy, and the ability of individuals to criticise the state is crucial to maintaining freedom.

In overseas colonies, the sedition laws were used precisely to suppress any local criticism of occupation by the British Crown. Gandhi, for example, was imprisoned for six years under the Sedition Act in India. After the country won its independence largely thanks to Gandhi’s civil disobedience, the first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru said in 1951 that this law was “highly objectionable and obnoxious” and “the sooner we get rid of it, the better.” Unfortunately, though, the law is still in force today, as comic artist Orijit Sen pointed out in frustration in a recent interview:

It is quite ironic that these laws were brought up by British to use against us and we are using them, even after 70 years of independence, against our own people. Also when you censor anything it gives an idea that people cannot be trusted. Censorship in all its forms is dangerous to society.

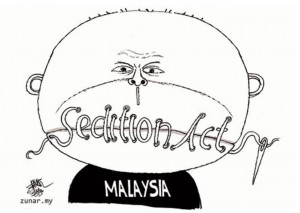

Some of the most vocal critics of Malaysia’s Sedition Act are also artists like political cartoonist Zunar, currently facing nine charges for statements he made on Twitter, and graphic designer Fahmi Reza, who was recently charged for creating a viral image of Prime Minister Najib Razak in clown makeup. Last year Zunar and two other defendants launched a legal challenge to the Act on the grounds that it predated and conflicted with independent Malaysia’s constitution. A court ruled against them in April, but one more level of appeal is still available.

Great Britain is not the only colonial power that instituted sedition laws overseas, of course. Indonesia’s top court in 2007 overturned that country’s law that had been introduced by the Dutch. And in the Philippines, a former colony of the United States, it is technically still a seditious act to steal or commandeer U.S. government property “for any political or social end” (Article 139.5). As recently as 2005, Article 142 of the same act also criminalized “inciting sedition” against the U.S. government, even though the Philippines has been independent since 1946. Dictator Ferdinand Marcos, for one, enthusiastically embraced the postcolonial gift of sedition laws, using them to intimidate and imprison journalists, artists, opposition lawmakers, and regular citizens who disagreed with his regime.

The United States itself also has not remained immune from unconstitutional regulation of speech in times of national anxiety. Over 200 years after the first U.S. Sedition Act was repealed, another one was passed by Congress in 1918 to specifically outlaw any criticism or action against the country’s involvement in World War I. At least 877 people were convicted under the law, many of them immigrants of German descent who aroused suspicion simply because of their background. The Supreme Court twice upheld the Act, but it was repealed by Congress in 1920.

In this season of election fatigue, Americans must not take for granted the right to criticize and even mock our elected officials. In too many so-called democracies around the world, that right has yet to be fully realized.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2016 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.