At the Cartoon Movement website, more than 400 political cartoonists from around the world have the chance to share their work internationally and build a community across borders. After remarking what seemed a high proportion of Italians among the contributors’ ranks, the editors of the Cartoon Movement blog recently brought together five of them for an interview about the development and current state of political cartooning in Italy, as well as the taboos and censorship applied to their work there.

Included in the interview were Cristina Bernazzini, Enrico Bertuccioli, Lamberto Tomassini (aka Tomas), Andrea Vitti and Emanuele Del Rosso. Like elsewhere in Europe, said del Rosso, satirical publications and cartoons in Italy saw a sharp rise after 1968, when student demonstrations in Paris blossomed into leftist movements across the rest of the continent. Italy in particular was hungry for satire, he says: “In a country in which bad politics and social issues are a day-to-day problem, the need for satire is strong.”

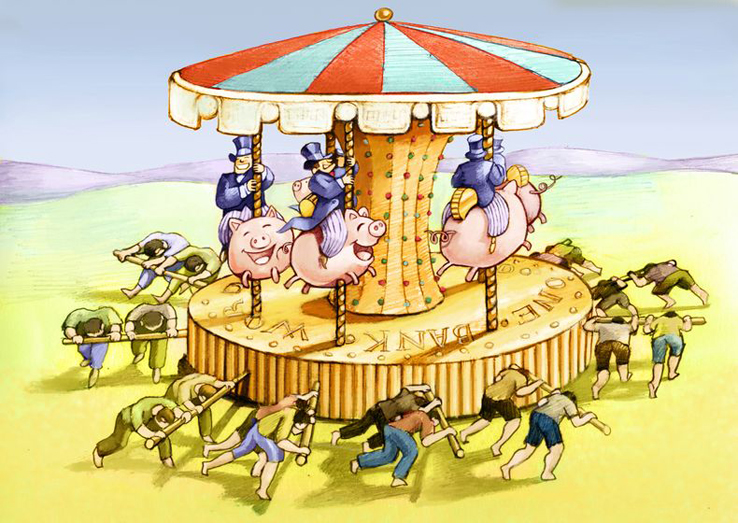

Tomassini added that satire plays a vital role in political debate, and must not be defanged:

I think that satire must always challenge authority, showing its flaws and faults to public opinion, which is sometimes too sleepy. Good satire can do this because of its revolutionary, utopian view which shows that an alternative reality is always possible.

Nevertheless, every country has its taboos, and the cartoonists all agreed that in Italy the strongest one surrounds religion, particularly Catholicism. “The fact that the Vatican State is in Rome is a problem for cartoonists working in newspapers or magazines,” said Bertuccioli. “They can be attacked for offending religious believers.”

But unlike in some countries where cartoonists are routinely subject to direct government censorship, Tomassini says the risk in Italy is that they will simply lose their edge by becoming too comfortable:

Here, more than risking censorship, satire tends to become weak. Cartoonists, in some cases, afraid of losing their good jobs, consider themselves like mere employees of the newspapers and accept the limits of the editorial line, through a self-censorship which betrays their vocation to intellectual freedom.

Like cartoonists everywhere, though, the Italians are finding it more difficult all the time to make a living from their chosen profession. Graphic novels are thriving, but the satirical magazines and newspapers of the 1970s and ‘80s are mostly gone now. The mainstream publications that do occasionally feature political cartoons often want to pay the artists in nothing but exposure–a model that Tomassini strongly rejects.

Check out the interview here, and click on the cartoonists’ names to see examples of their work!

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2016 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.