When the first draft of the self-imposed Comics Code was drawn up in 1954, virtually every clause directly addressed some point of criticism that had come up in that year’s Senate hearings, which probed for some causal link between comics and juvenile delinquency. Chief among the critics was Dr. Fredric Wertham, the self-appointed expert on the issue who also did a brisk business publishing alarmist articles in the popular press and his own book Seduction of the Innocent. There was however one charge leveled by Wertham that wound up being reinforced by the Code but nevertheless caused an identity crisis in comics: that is, the fascistic overtones of superhero stories.

When the first draft of the self-imposed Comics Code was drawn up in 1954, virtually every clause directly addressed some point of criticism that had come up in that year’s Senate hearings, which probed for some causal link between comics and juvenile delinquency. Chief among the critics was Dr. Fredric Wertham, the self-appointed expert on the issue who also did a brisk business publishing alarmist articles in the popular press and his own book Seduction of the Innocent. There was however one charge leveled by Wertham that wound up being reinforced by the Code but nevertheless caused an identity crisis in comics: that is, the fascistic overtones of superhero stories.

In an in-depth article for NPR’s Monkey See pop culture blog, Glen Weldon, author of Superman: The Unauthorized Biography, noted that Wertham labeled the Man of Steel an “un-American fascist” whose “whole schtick was hurting criminals without getting hurt himself.” Even more troubling to Wertham, himself a German-born Jew who moved to the U.S. in the 1920s, was Superman’s membership in an alien “super-race” that seemed uncomfortably close to Nazi philosophies.

Although the character’s original creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were also Jewish, Weldon argues that this particular point from Wertham “hit a nerve” in the industry during the post-war era, and creators slowly began moving towards introspective and conflicted superheroes who did not take their powers lightly. The epitome of the new breed, of course, was Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’s Spider-Man, who came on the scene in 1962 with the now-familiar maxim: “With great power comes great responsibility.”

Ironically, though, the Wertham-inspired Comics Code required creators to tread carefully as they began to produce storylines that questioned absolute authority. The third clause in the original 1954 Code stated that “policemen, judges, Government officials and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.” It was not until 1971 — perhaps not coincidentally, two years after Richard Nixon took office — that the Code was updated to allow occasional depictions of corrupt public officials, provided that they were appropriately punished.

By the 1980s, says Weldon, comics began to directly deconstruct their heroes’ authoritarian roots rather than trying to distance themselves from uncomfortable truths:

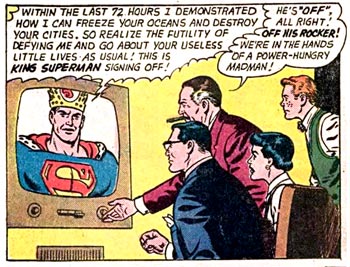

In books like Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns, Kingdom Come, Empire, Civil War and many others, creators explicitly grappled with how heroes exert their will when their penchant for benign intervention becomes … less-than-benign. In monthly comics and one-shot tales set in alternative universes, scores of superheroes became dictators (often for “the greater good”) and crushed any insurrection that would upset their status quo.

Weldon’s full article at Monkey See is well worth a read! Check it out here.

We need your help to keep fighting for the right to read! Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.