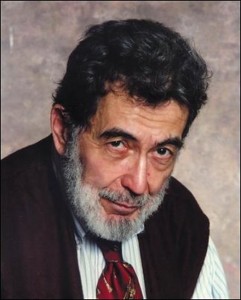

Writer, jazz critic, and First Amendment advocate Nat Hentoff passed away on Saturday, January 7, at the age of 91. A passionate and sometimes combative champion of civil liberties, Hentoff’s contributions as a political commentator and a jazz critic were commemorated by outlets around the country.

Writer, jazz critic, and First Amendment advocate Nat Hentoff passed away on Saturday, January 7, at the age of 91. A passionate and sometimes combative champion of civil liberties, Hentoff’s contributions as a political commentator and a jazz critic were commemorated by outlets around the country.

Hentoff was a long-time political columnist and jazz critic for several publications, including decades-long runs with The New Yorker, The Washington Post, and Village Voice. Hentoff earned several awards and honors over his career, including the Guggenheim fellowship (1972), the American Library Association‘s Imroth Award for Intellectual Freedom (1983), and the National Press Foundation’s award for lifetime distinguished contributions to journalism (1995). He was twice nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in Commentary (1999 and 2002), and Hentoff was also the first nonmusician to be named a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts.

In their articles about Hentoff’s accomplishments, several outlets described his contributions to journalism and his Constitutional absolutism, in particular with regard to the First Amendment, and painted a portrait of a man who comfortably held views from both the left and the right sides of the political spectrum.

Martin Weil remembers Hentoff for The Washington Post, sharing a quote from Hentoff about his love for both free expression and jazz:

“Duke Ellington used to tell me that ‘we gave the world the freest expression ever in the arts,’ so I always thought there was a natural tie there,” Mr. Hentoff told The New York Times. “The whole idea of the Bill of Rights and jazz [is] freedom of expression that nobody, not even the government, can squelch.”

Of the 10 amendments in the Bill of Rights, Mr. Hentoff was most closely identified with the First, the one that guarantees freedom of speech and of the press as he derided and denounced what he perceived as efforts at censorship by the left and the right.

From Robert D. McFadden at The New York Times:

The Hentoff bibliotheca reads almost like an anthology: works by a jazz aficionado, a mystery writer, an eyewitness to history, an educational reformer, a political agitator, a foe of censors, a social critic. He was — like the jazz he loved — given to improvisations and permutations, a composer-performer who lived comfortably with his contradictions, although adversaries called him shallow and unscrupulous and even his admirers sometimes found him infuriating, unrealistic and stubborn.

Hentoff’s free expression advocacy also found a home in his fiction novels, as NPR‘s James Doubek illustrates:

His 1982 novel The Day They Came to Arrest the Book tells the story of a high school that seeks to remove the book Huckleberry Finn from the school curriculum and library over racism and other issues. A student from the school newspaper fights the effort — an allegory on censorship.

NPR’s As It Happens also shared recordings of Hentoff from their archives (via the Cato Institute):

From Hillel Italie with the Associated Press:

As a columnist, Hentoff focused tirelessly on the Constitution and what he saw as a bipartisan mission to undermine it. He tallied the crimes of Richard Nixon and labeled President Clinton’s anti-terrorism legislation “an all-out assault on the Bill of Rights.” He even parted from other First Amendment advocates, quitting the American Civil Liberties Union because of the ACLU’s support for speech codes in schools and workplaces.

Daniel Kreps of Rolling Stone writes:

[In 1958] Hentoff joined the Village Voice, where he served as columnist for the next 50 years, writing about a myriad of subjects involving politics, education, religion and, most importantly to him, freedom of speech and First Amendment issues.

We need your help to keep fighting for the right to read! Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!