The New York Times announced without much fanfare last week that its bestseller lists for graphic books and manga will soon be discontinued, sending shockwaves through the publishing industry and some librarians scrambling to find alternate barometers of public demand for sequential art. For librarians and educators the lists often function not so much as an indicator of what to buy, but as concrete evidence of the format’s popularity and worth to be shared with skeptical parents, administrators, and governing boards.

The New York Times announced without much fanfare last week that its bestseller lists for graphic books and manga will soon be discontinued, sending shockwaves through the publishing industry and some librarians scrambling to find alternate barometers of public demand for sequential art. For librarians and educators the lists often function not so much as an indicator of what to buy, but as concrete evidence of the format’s popularity and worth to be shared with skeptical parents, administrators, and governing boards.

After some initial confusion on social media, Times Book Review editor Pamela Paul clarified that “comics will still be counted on the main [hardcover and paperback] lists, as they were before we spun them off separately” but acknowledged to the Washington Post that “obviously the bar will be raised a little bit higher for books to become New York Times bestsellers.”

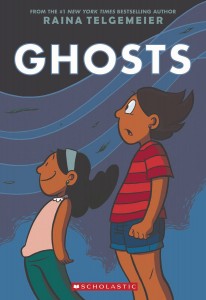

Several publishers and creators expressed dismay and confusion at the announcement. Raina Telgemeier, who currently holds five out of ten spots on the Paperback Graphic Books list, thanked Paul for a promise of expanded future coverage of the format in reviews and features, but added that “the list also SUPER validated new voices in the comics medium. We all benefited.”

News coverage of the changes has thus far focused on reactions within the comics industry, but has mostly overlooked the Times lists’ utility for collection development in libraries and schools. In a Facebook group for librarians who deal with graphic novels, the response was swift and vocal. Although many members were already using some combination of online and print reviews, patron requests, and other lists from Diamond and Publishers Weekly in addition to the Times to identify titles for their collections, several cited the very existence of the Times Graphic Books lists as support against colleagues and supervisors who may (still!) question the value of comics in libraries and classrooms.

The Times lists can also be valuable ammunition in defending challenged books, since would-be censors often present arguments along the lines of “no one wants to read this sort of thing.” Moreover, the lists drive both patron discovery and sales to libraries: when a book breaks into the top 10 on a Times list, many libraries anticipate a surge in demand by adding more copies even if they already had some.

To partially make up for the loss of the Times lists, participants in ALA’s Graphic Novels and Comics in Libraries Member Interest Group are already brainstorming plans to compile other pertinent collection development resources for easy reference. But as Polygon’s Susana Polo points out, the decision to eliminate this important metric for a booming sector of publishing is hard to explain:

At a point where cartoonists like Alison Bechdel and Gene Luen Yang are getting MacArthur Genius grants and a graphic novel can win the National Book Award, it’s difficult to understand how The New York Times could call the eight-year inclusion of comics in the paper’s best seller lists an “experiment” that apparently failed.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2017 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.