Recently a children’s librarian wrote to Pat Scales, School Library Journal’s anti-censorship advice maven, with a workplace dilemma. It seems that a fellow librarian who works on one of their large system’s bookmobiles had requested not to receive any books from either the Captain Underpants or Diary of a Wimpy Kid series for her collection “because she finds them offensive.” This may be an extreme case (e.g., a very easily offended librarian), but Scales’ response exemplifies one of the key ethical principles of our profession: putting aside our own personal views to offer materials that the community wants.

Recently a children’s librarian wrote to Pat Scales, School Library Journal’s anti-censorship advice maven, with a workplace dilemma. It seems that a fellow librarian who works on one of their large system’s bookmobiles had requested not to receive any books from either the Captain Underpants or Diary of a Wimpy Kid series for her collection “because she finds them offensive.” This may be an extreme case (e.g., a very easily offended librarian), but Scales’ response exemplifies one of the key ethical principles of our profession: putting aside our own personal views to offer materials that the community wants.

As Scales points out, the bookmobile librarian in this scenario seems “confused about her job description.” All librarians occasionally or often handle books or other materials that are not what we would choose for ourselves, but ideally we all should have learned in graduate school that some people do enjoy those items for their own reasons–or in the immortal words of Judge John Hodgman, “people like what they like.”

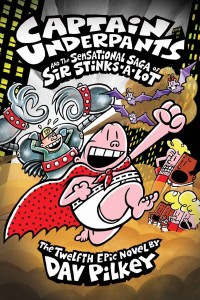

In this case, it seems that the bookmobile librarian’s particular bias may be against children’s books that she considers “unserious,” for want of a better word. Objections to Dav Pilkey’s Captain Underpants series are nothing new; it has appeared on ALA’s annual top ten list of frequently challenged books at least five times, and topped the lists in 2012 and 2013. While kids find characters like Super Diaper Baby, Professor Poopypants, and Tippy Tinkletrousers to be quite uproarious (and also a great enticement to keep reading), some adults seem less amused.

Jeff Kinney’s Diary of a Wimpy Kid is another matter, and it’s difficult to see what objection the librarian could have to the wildly popular series that began life as a webcomic. In light of the deceptively simple stick-figure cartoons scattered throughout the books that purport to be journals of main character and middle schooler Greg Heffley, it’s tempting to conclude that this is simply a case of bias against sequential art, which has often been tarred as “low culture” since at least the 1940s in the U.S.

Whatever the case, Scales rightly concludes that if the bookmobile librarian cannot put aside her personal biases in order to handle materials that both parents and kids are requesting, then she should not be dealing with the public. As it is now, she is failing to uphold the very first clause of the Library Bill of Rights which states that materials “should be provided for the interest, information, and enlightenment of all people of the community the library serves.”

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2017 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.