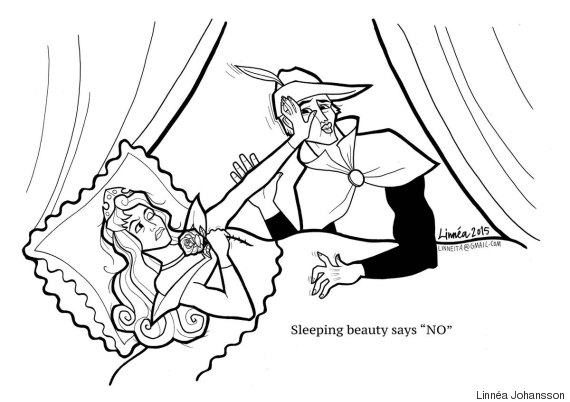

From Super-Strong Princesses coloring book by Linnéa Johansson

A mother in North Tyneside, UK set off a bit of a British media frenzy last week with her request to remove a version of Sleeping Beauty from her six-year-old son’s school curriculum because the story might suggest to “children that it is OK to kiss a woman while she’s asleep.” Sarah Hall posted pictures from the book on Twitter with the hashtag #MeToo, drawing a connection to the current wave of women speaking up about sexual harassment and assault.

Hall also made a formal request to have versions of the story that include the non-consensual kiss removed from her son’s grade level at the school which remains unidentified in media reports. She said she does not object to it being used with older children, with whom “you could have a conversation around it, you could talk about consent, and how the Princess might feel.”

The specific Sleeping Beauty adaptation at issue in this case is actually from an early reading and phonics curriculum called “Read with Biff, Chip and Kipper” which is published by Oxford University Press and used in about 80% of UK primary schools, according to the publisher’s website.

The now-familiar kiss to wake the sleeping princess, however, was largely fixed in the popular imagination by the 1959 Disney film version. Although the opening credits cite 17th century French writer Charles Perrault’s version as its source, it is actually closer to the 19th century version adapted by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in Germany, who in turn collected most of their tales from women who recited them orally.

Perrault’s adaptation, written in the midst of a woman-dominated literary fairy tale fad at the court of Louis XIV, actually reflects aristocratic mores of his time–including the prince keeping a respectful distance from our heroine until she is at least conscious. (The subsequent subplot about his mother being an ogress who wants to eat her new daughter-in-law and grandchildren is another matter altogether, and definitely did not make the Disney film.)

It is uncertain whether the non-consensual kiss was a particular innovation of the Grimms or their oral sources, but the point is that fairy tales–like all folklore–have never been immutable. Different versions of all the tales familiar to us today have existed in tandem since well before Perrault, and the largely inactive role accorded to the heroine in this particular tale has already come in for plenty of feminist critique and subversion over the years–from the coloring book page shown above to a 2011 edition of the webcomic Rhymes With Witch by R.K. Milholland.

Children’s literature also has its share of innovative Sleeping Beauty adaptations. While Hall implies that only older children could be led to consider issues of consent in relation to the “traditional” Disneyfied story, there seems to be no reason why six-year-olds like her son couldn’t read or listen to the gender-swapped Sleeping Bobby or the cosmopolitan Sleepless Beauty in juxtaposition with the version from their reading curriculum. As with so many instances of well-meaning parents wanting to shield their children from real-world problems, the best solution here is to respect young readers enough to let them think for themselves.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2017 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.