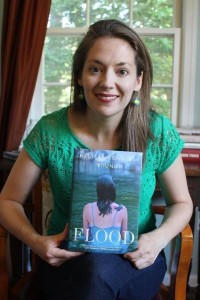

Author and educator Melissa Scholes Young wrote an op-ed for the Washington Post explaining why she doesn’t censor the books her children read. While this position likely splits mosts parents down the middle between those that wholeheartedly agree and those that feel their pulse quicken at the thought of finding Fifty Shades of Gray in their teenager’s backpack, Young’s experience as a parent, a teacher, and her eloquence as an author all converge in a convincing essay well worth the read.

Author and educator Melissa Scholes Young wrote an op-ed for the Washington Post explaining why she doesn’t censor the books her children read. While this position likely splits mosts parents down the middle between those that wholeheartedly agree and those that feel their pulse quicken at the thought of finding Fifty Shades of Gray in their teenager’s backpack, Young’s experience as a parent, a teacher, and her eloquence as an author all converge in a convincing essay well worth the read.

As both a parent and a teacher of middle school, high school and college students, I’ve found that reading begins more discussion than it ends. Reading about experiences different from our own encourages us to travel with our minds, and as Twain said, “Travel is fatal to prejudice.” Twain knew well the loss when work is censored. “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” published in 1885, is one of the most frequently challenged books in our country. The language of the novel, especially his treatment of class and race, is difficult to digest by our modern standards. But if we dismiss “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” for its imperfections, we miss the opportunity to learn from Twain’s humanitarianism, which is larger than his book’s pitfalls.

Young is in no way advocating abandoning children to the whims of popular fiction. Quite the reverse, in fact, her method comprises of total involvement with what her kids are reading. Whether scanning the titles as they check out books at the library, researching works she is less familiar with, or committing to reading along with her kids, as she did with Trevor Noah’s memoir and The Hunger Games Young is proactively in the background ready to discuss mature content and themes, and any questions that these books raise.

Last summer, we read Angie Thomas’s “The Hate U Give,” a story about an unarmed black teenager killed by police. After hearing that some school districts in Missouri and Texas challenged the book, a parent at our bus stop asked if I was concerned about the violence or language. I told him I’d rather my kids read about racial profiling through an honest, intelligent narrator than see it on the nightly news.

Young goes on to mention that the language and the violence in the book are less disturbing to her, and surely to many who love the book, then the police violence that the book addresses. As a teacher, Young often found parents concerned about assignments, wishing to protect their children, which is noble but perhaps misguided. “My students are often more mature than their parents realize and they can navigate nuances and engage in critical conversations with open, unformed opinions.”

Give the full piece a read here. Whether or not everyone agrees with her, her credentials and passion are beyond reproach. And she is raising her children to think critically and love literature, both noble goals all parents strive for.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!