by Brian M. Puaca

The recent success of the Black Panther movie has prompted many viewers to delve into the history of the character and explore his origins in the Marvel Universe of the 1960s. As rightly noted in many media outlets, the Black Panther was the first black superhero to appear in mainstream comics. This realization has prompted greater interest in the representation of black characters in comic books during the 1950s and 1960s. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there have been some observers on social media that connect the absence of black superheroes to the standards and enforcement of the Comics Code Authority (CCA) established in 1954. One popular post (shared by others more than 5,000 times on Facebook following the Black Panther film premiere) referenced the CCA and stated that black characters were “literally and legally banned from comics (and other media) for years.” But is this really so?

The Comics Code Authority is a convenient explanation for the absence of black superheroes through much of the Silver Age, yet such an assertion merits careful consideration. When reviewing the standards published in the Comics Code Authority there is only one passage that is connected to the issue of race. In a provision under the heading “Religion,” the Code states that “ridicule or attack on any religious or racial group is never permissible.” In light of this, there is certainly no basis in the CCA language to restrict the appearance of black characters in mainstream comics during the Silver Age.

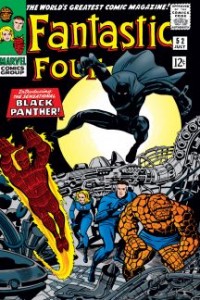

Furthermore, a number of black characters did in fact appear in Code-approved books after 1954. Marvel’s Jungle Tales featured Waku, Prince of the Bantu, written by Stan Lee during the mid-1950s. In the early 1960s, Stan Lee included Gabe Jones, an African-American soldier, as a core member of Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos. Jones made regular appearances in the title and has even made it into the Marvel Cinematic Universe in recent years. Black Panther may have been the first black superhero, appearing in Fantastic Four #52, in 1966, but just a few years later, The Falcon was the first African-American superhero. The Falcon’s first appearance in Captain America was on newsstands just as Neil Armstrong walked on the moon in the summer of 1969. Most importantly, all of these Code approved books appeared before the first revision of the CCA, which occurred in 1971. All of these black characters entered into comics with the original CCA language in place.

In light of this evidence of black characters gaining increasing prominence in Code-approved books during this period, how does one explain the popular belief in the Code’s ban on black characters? More often than not, such claims about the racism of the CCA are connected to the infamous episode where EC Comics publisher William Gaines was asked to remove a black astronaut in the final panel of a story entitled “Judgment Day.” Exploring the tensions between two groups of differently colored robots, “Judgment Day” offered a transparent critique of institutionalized racism in the United States. The story had actually first appeared in print in 1953, but it was now subject to Code scrutiny when it was set to be reprinted in Incredible Science Fiction #33 in early 1956.

There is little doubt, even from Gaines himself, that the fact that the main character in “Judgment Day” was black concerned the CCA. Yet there are several reasons for the Code’s rejection of the story that merits consideration beyond the astronaut’s race. First, the publishers who had banded together to create the Code did so in order to survive and avoid governmental interference. And those publishers undoubtedly saw EC as the main lightning rod of popular discontent. So it is probable that CCA director Charles Murphy was acting in a fashion consistent with their wishes when he antagonized EC. The fact that Murphy’s final verdict was that the story could run if the artist removed the beads of sweat from the black astronaut’s forehead suggests that much of the controversy was personality driven. Second, highlighting American hypocrisy in the midst of the Cold War would hardly endear most Americans to comic books, so it is likely that Murphy objected to EC’s broader critique of institutionalized racism in the United States. Murphy must have realized that the last thing the industry needed was more books garnering bad publicity for their political content. The Code then did not systematically ban black characters from comics, but they objected when used by creators to illustrate the hypocrisies present in contemporary American society.

The Black Panther has always been a popular character, and that popularity has significantly increased since the release of the fantastic film by Ryan Coogler. The character is one that holds great significance in the history of modern comics and holds great personal meaning for fans that relate to him. Asking questions about the character’s origins means that there are more viewers – and readers, hopefully – who are interested in the Black Panther’s past and the world in which Lee and Kirby created him. It is precisely because of this great importance and the growing interest in him that we need to think carefully about the past and not rely on simple, convenient explanations. Preserving accurate history in comics is important, and thinking critically about news articles and social media posts that confirm personal confirmation basis is critical to doing that. The Comics Code undoubtedly did great harm to the comic industry in the 1950s and 1960s, but the evidence does not support the claim that the CCA unilaterally banned black characters.

Nama, Adilifu. Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2011.

Nyberg, Amy. Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code Authority. Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi Press, 1998.

Wright, Bradford. Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Brian M. Puaca is an associate professor of history at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia, where he teaches a course on the history of comic books and American society. He can be reached at bpuaca@cnu.edu