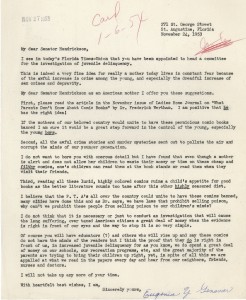

“If the mothers of our beloved country would unite to have these pernicious comic books banned I am sure it would be a great step forward in the control of the young, especially the young boys.” – Eugenia Y Genovar, Letter to Senator Hendrickson, November 24, 1953

Teaching Comics and Censorship: The National Archives and the 1954 Senate Subcommittee Hearings

by Brian M. Puaca

Almost sixty-five years after the Senate’s investigation of comic books and juvenile delinquency, evidence from these hearings can be found by searching the records in the National Archives. Within these resources, the National Archives has digitized two letters sent to the chair of the subcommittee, Senator Robert Hendrickson (R-NJ), regarding the relationship between comics and crime. The first, an eloquent typewritten letter advocating censorship, comes from a mother in Florida. The second, a handwritten message scrawled on lined paper in defense of comic books, was written by a fourteen year old boy from rural Pennsylvania. However, the aesthetic presentation of their views should not be conflated with the persuasiveness of their ideas. One letter uses slippery logic to promote the wholesale banning of comic books, while the other serves as a blunt, albeit simplistic, defense of First Amendment rights. These respective sources reveal a great deal about popular concerns related to comics in the early 1950s. Furthermore, their words still resonate in the 21st century as debates about comics and censorship continue.

Upon learning of Hendrickson’s appointment to head the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency in late 1953, Eugenia Genovar sent the New Jersey senator a letter of support. In her letter, Genovar made an appealing case for the censorship of comic books. First, she encouraged Hendrickson to read the work of Frederic Wertham, the author of the Seduction of the Innocent, who endorsed sweeping restrictions on the sale of comics to children. Wertham himself would indeed be called to testify at the subcommittee hearings in New York City in April 1954. Second, she argued that the parental monitoring of comic books is insufficient since her son would only encounter the troubling material at the houses of friends or on the newsstand. Third, she claimed, “reading all these lurid, highly colored comics ruins a child’s appetite for good books as the better literature sounds too tame after this other highly seasoned diet.”

But the most damning indictment comes near the end of her letter when Genovar confuses correlation with causation. She asserted there was no need for a costly investigation “when the evidence is right in front of our eyes and the way to stop it is so very simple.” Genovar assumed a direct relationship between the increase in comic book sales following World War II with the rise in juvenile delinquency, as Wertham would do in his published works. The wholesale prohibition of comics, which she equated with poison, was ultimately her solution.

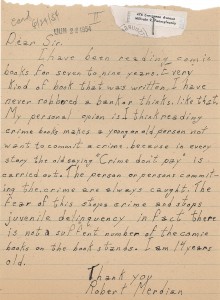

The second letter comes from Robert Merdian, who contacted Senator Hendrickson in June 1954, following the conclusion of the subcommittee hearings but before the creation of the Comics Code Authority. Merdian, who was fourteen, sent a letter describing his own experiences reading comics for “seven to nine years.” His note, despite being littered with misspellings and grammatical errors, made a straightforward case. Merdian argued in his letter that the crime stories he read in comic books served as a deterrent since the criminals were always caught and punished. He stated that the fear of getting caught “stops crime and stops juvenile delinquency.” But in what is the most notable statement in his letter, the young man explained to Hendrickson that he has read all kinds of comic books and has never even thought about robbing a bank. Here Merdian, perhaps without realizing he is doing so, cautioned the senator from assuming that comic book readers internalize and act on the ideas they encounter in fictionalized stories. In this disarmingly simple statement, Merdian underscored the flawed logic used by so many critics of comic books during the early Cold War as they assumed a causal relationship between comic books and youth criminality. Indeed, the letter prompts one to consider what other issues might influence young Americans to commit crimes, since plenty of comic books readers, like Merdian, did not become delinquents.

Unsurprisingly, critics of comic books advocated censorship as a means to combat juvenile delinquency in the early 1950s. First, this approach was the most simple response and one that could systematically remove material that authorities deemed objectionable. While some critics acknowledged that censoring comics was not necessarily a “silver bullet” that would prevent juvenile delinquency, some people, like Eugenia Genovar, the aforementioned Florida mother, undoubtedly viewed it as one. Second, using comics as a scapegoat for an increase in juvenile delinquency avoided any deeper examination of broader American social and cultural problems. Acknowledging that there were societal concerns that needed to be addressed was not only a much more complicated issue for legislators to tackle, it also suggested weakness at a time of extreme anxiety brought on by the Red Scare. Finally, the work of Frederic Wertham made a compelling clinical case for extensive restrictions on the content of comics. It is important to note here that Wertham had medical credentials that gave him great authority in the public debates on comic book censorship. Yet his readers were unaware of the highly questionable methods he used to build a persuasive case. As Carol Tilley demonstrated in her outstanding article “Seducing the Innocent: Frederic Wertham and the Falsifications that Helped Condemn Comics” Wertham “manipulated, overstated, compromised, and fabricated evidence…for rhetorical gain.”

Educators with an interest in comics, the Cold War, and modern American history more generally should take advantage of these easily accessible sources. Certainly, these two letters in the National Archives would be valuable complements to other texts — such as Wertham’s book, the testimony of witnesses at the subcommittee hearing, and the Comics Code Authority — when studying the debates about comic books and censorship in the 1950s. Yet they also provide insight into broader tensions within American Cold War society, generational debates about popular culture, and the agency of young people as political actors. These issues transcend the narrow boundaries of the post World War II era. And perhaps most notably, these sources encourage students and educators alike to think carefully about argumentation, logic, and evidence. Moreover, they serve as a reminder that we should always be critical in our reading of sources. We should always consider how historical context shapes documents and their presentation. And we should always investigate the bias of authors who seek to convince us of their beliefs. These lessons are as useful today as they have ever been.

Sources

Letter from Eugenia Y. Genovar Regarding Comic Book Censorship, November 24, 1953 [Committee Papers 1816-2011]; Records of the U.S. Senate, 1789-2015, Record Group 46; National Archives at College Park, MD [online version available through the Archival Research Catalog (ARC identifier 6120051) at www.archives.gov, May 24, 2018.] https://catalog.archives.gov/id/6120051

Letter from Robert Merdian Regarding Comic Book Censorship, June 22, 1954 [Committee Papers 1816-2011]; Records of the U.S. Senate, 1789-2015, Record Group 46; National Archives at College Park, MD [online version available through the Archival Research Catalog (ARC identifier 6120050) at www.archives.gov, May 24, 2018.] https://catalog.archives.gov/id/6120050

The Comics Code of 1954. https://cbldf.org/the-comics-code-of-1954/

The Frederic Wertham Papers at the Library of Congress. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms010146

U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency Hearings Transcripts, April and June 1954. http://www.thecomicbooks.com/1954senatetranscripts.html

Brian M. Puaca is an associate professor of history at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia, where he teaches a course on the history of comic books and American society. He can be reached at bpuaca@cnu.edu.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2018 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!