With the meteoric success of the streaming show The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, which just released its third season, a free speech icon has returned to pop culture prominence. Lenny Bruce has long been held as the father of modern stand-up, and a true believer of the First Amendment. Bruce was arrested many times in his life, frequently for obscenity, which never dissuaded him from continuing to speak freely on stage and off. Of the many roles Bruce was capable of, posthumous sit-com character probably isn’t one he would have anticipated.

When the latest season of Mrs. Maisel dropped, fans were quick to take to social media to herald the return of Lenny Bruce played by Luke Kirby, who recently took home an Emmy for the role. Showrunner Amy Sherman-Palladino is careful with the real-life comedian’s memory and uses historical events and Bruce’s real jokes to keep the character faithful to the man. One theme that has recurred in the show most frequently when Bruce shows up is Free Expression, something he valiantly stood for in life. It’s hard not to hope, as scores of viewers watch Bruce get arrested for language we now can spot in a PG-13 movie, that the absurdity of censorship sparks an interest in the cause that Lenny Bruce fought so hard for and sadly didn’t live to see the great effect he had.

CBLDF Obscenity Case File: People vs. Bruce

In his song Lenny Bruce, Bob Dylan sings:

In his song Lenny Bruce, Bob Dylan sings:

They said that he was sick ’cause he didn’t play by the rules

He just showed the wise men of his day to be nothing more than fools

They stamped him and they labeled him like they do with pants and shirts

He fought a war on a battlefield where every victory hurts

Lenny Bruce was bad, he was the brother that you never had

In modern times, Lenny Bruce’s legacy is that of a martyr for his suffering at the hands of those who believed his stand-up comedy was too “obscene” for its time. The irony is that his comedy is now recognized for paving the way for much of modern comedic entertainment. Of course, the downside to martyrdom is that the martyr rarely lives to see his name championed. Although his influence spans everything from the sets of modern comedians to the pages of popular comic books, Bruce’s battle with uptight authorities cost him his career, his livelihood, and ultimately his life.

Bruce’s rise to prominence began in the 1950s. A stand-up comedian, his knack for weaving profanity and scathing honesty into his routines made him a hit on the club circuit. By the early 1960s, he had been dubbed “the most shocking comedian” of the day. His act led him to some of the most prestigious venues in the country, including New York’s hallowed Carnegie Hall. Tragically, the same biting use of satire that was responsible for his rise to fame also facilitated his undoing.

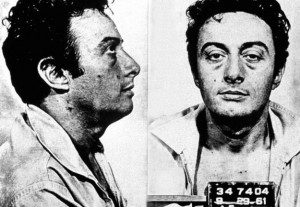

Beginning in the 1960s, authorities in many of the cities Bruce regularly performed in declared his act obscene. A string of arrests followed. In 1961, he was arrested in San Francisco and charged with violating the California obscenity law (a charge of which he was later acquitted). In 1962, he was arrested twice in Los Angeles and once in Chicago for violating California and Illinois obscenity laws (he beat the LA charges but was convicted in Chicago). In 1963, he was ordered to leave England after British authorities got wind of his performance at a London club. In 1964, California authorities arrested him for a third time for allegedly violating the California obscenity law.

Tired of being harassed by the state of California, Bruce took his act to New York City. In March 1964, he booked a run of shows at a Greenwich Village club named the Café Au Go Go. Unfortunately for Bruce, New York City authorities were poised to treat him as unfairly as their West Coast counterparts had. On the nights of March 31 and April 1, the New York City District Attorney’s Office sent undercover investigators to two of Bruce’s Café Au Go Go performances. Over the course of those two shows, Bruce put on a number of his standards, including: “To Come as a Preposition,” “Infidelity,” “Red Hot Enema,” and “Guys Are Carnal.” He also threw in some new material regarding the fit and form of various former first ladies (most notably, Eleanor Roosevelt).

Based on the information the NYC investigators collected at the shows, the District Attorney’s Office was able to convince a grand jury to indict Bruce for violating the New York obscenity law. Specifically, it charged Bruce with violating New York Penal Code 1140, which barred “obscene, indecent, immoral, and impure dram, play, exhibition, and entertainment . . . which would tend to the corruption of the morals of youth and others.”

Bruce, armed with attorneys Ephraim London and Martin Garbus (the former a leading First Amendment lawyer, the latter his protégé) disputed the charges. At trial, the prosecution relied on testimony from the investigators sent to attend Bruce’s performances. Some of the investigators read from hand-written notes they had taken during Bruce’s acts, recounts that butchered the performance of Bruce’s material. This caused Bruce to lament, “I’m going to be judged by his bad timing, his ego, his garbled language.” In addition to the investigators, the prosecution presented testimony from sociologists, professors, and literary experts who commented on the merit, decency, and community impact of Bruce’s act.

Bruce, armed with attorneys Ephraim London and Martin Garbus (the former a leading First Amendment lawyer, the latter his protégé) disputed the charges. At trial, the prosecution relied on testimony from the investigators sent to attend Bruce’s performances. Some of the investigators read from hand-written notes they had taken during Bruce’s acts, recounts that butchered the performance of Bruce’s material. This caused Bruce to lament, “I’m going to be judged by his bad timing, his ego, his garbled language.” In addition to the investigators, the prosecution presented testimony from sociologists, professors, and literary experts who commented on the merit, decency, and community impact of Bruce’s act.

Bruce’s legal team countered by presenting testimony from their own expert witnesses. These included reputable psychiatrists, who testified that Bruce’s performance was not sexually arousing; New York media experts, who testified that the performance did not offend local community standards; and literary/art critics, who testified to the social importance of Bruce’s brand of humor. Bruce also presented a petition from a coalition of entertainers and authors that included Allen Ginsberg, Paul Newman, Bob Dylan, Elizabeth Taylor, and Norman Mailer, among others. The petition read “Whether we regard Bruce as a moral spokesman or simply as an entertainer, we believe he should be allowed to perform free from censorship or harassment.”

Perhaps the strongest of Bruce’s witnesses was journalist Dorothy Kilgallen, who described Bruce as “a brilliant satirist,” labeled his social commentary as “extremely valid and important,” and testified that “Lenny Bruce, as a nightclub performer, employs these words the way James Baldwin or Tennessee Williams or playwrights employ them on the Broadway stage — for emphasis or because that is the way that people in a given situation would talk. They would use those words.”

Despite Bruce’s efforts, the court found his performances “obscene, indecent, immoral and impure within the meaning of the [New York] penal code” and sentenced him to “four months in the workhouse.” In its final opinion, the court concluded that Bruce’s act “appealed to prurient interest,” was “patently offensive to the average person in the community,” and lacked “redeeming social importance.” Bruce would go on to appeal the conviction, but died of a morphine overdose before his case reached an appellate court.

Despite Bruce’s efforts, the court found his performances “obscene, indecent, immoral and impure within the meaning of the [New York] penal code” and sentenced him to “four months in the workhouse.” In its final opinion, the court concluded that Bruce’s act “appealed to prurient interest,” was “patently offensive to the average person in the community,” and lacked “redeeming social importance.” Bruce would go on to appeal the conviction, but died of a morphine overdose before his case reached an appellate court.

It wasn’t until 2003, when a team of First Amendment advocates, including CBLDF General Counsel Bob Corn-Revere, convinced then New York Governor George Pataki to issue Bruce the first posthumous pardon in the state’s history. When issuing the pardon, Governor Pataki characterized it as “a declaration of New York’s commitment to upholding the First Amendment.”

Satire, no matter how biting or expletive-ridden, is an important form of expression. Just as a comedian’s monologue can be used to satirize a perceived societal pomposity, ridiculousness, or hypocrisy, so too can a comic book or graphic novel. In the decades since Lenny Bruce’s passing, First Amendment advocates have fought hard to combat those who would censor speech by applying vague “obscenity” standards and creating subjective definitions of “redeeming social importance” and “community standards.”

CBLDF remains on the front lines of the battle to protect satirical speech, working to ensure the efforts of trailblazers like Lenny Bruce were not in vain. Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Rick Marshall is an attorney who recently finished work on a legal master’s degree in Intellectual Property law at the George Washington University Law School.

Additional research and references in this piece were previously compiled by Doug Linder in his article “The Trials of Lenny Bruce” available at http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/bruce/bruceaccount.html (last visited 1/28/2013).