Today marks the 5th anniversary of the gruesome Charlie Hebdo attack, where two brothers, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, forced their way into the newspaper’s office and killed 12 people, injuring 11 more. At the time of the tragedy, the world was horrified by the violence against the paper – a rally for national unity took place less than a week later with 40 world leaders present as part of the group of 2 million, and an additional 3.7 million joining in demonstrations all across France, everyone chanting “Je suis Charlie” or “We are Charlie.” Five years later, we look back in sadness at these attacks and wonder, are we all still Charlie? Or was this attack just the beginning of a normalization of violence against the press that erodes free expression around the world.

Today marks the 5th anniversary of the gruesome Charlie Hebdo attack, where two brothers, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, forced their way into the newspaper’s office and killed 12 people, injuring 11 more. At the time of the tragedy, the world was horrified by the violence against the paper – a rally for national unity took place less than a week later with 40 world leaders present as part of the group of 2 million, and an additional 3.7 million joining in demonstrations all across France, everyone chanting “Je suis Charlie” or “We are Charlie.” Five years later, we look back in sadness at these attacks and wonder, are we all still Charlie? Or was this attack just the beginning of a normalization of violence against the press that erodes free expression around the world.

Charlie Hebdo Murders

The morning of the attack, January 7 2015, the staff of Charlie Hebdo were gathered in the unmarked work space they had moved to after their previous office was firebombed four years earlier. They sat waiting for the first editorial meeting of the New Year to begin. Nearby, two gunmen and brothers, left a different building looking for the newspaper, when they located the correct building and Hebbbdo cartoonist Corinne “Coco” Rey. The men threatened Rey to get her to open the locked door with work credentials.

The brothers entered the office of Charlie Hebdo, firing a spray of bullets through the lobby, killing Frédéric Boisseau, a maintenance worker. They forced Rey at gunpoint to take them to the editorial meeting still underway upstairs. Once they entered, the killers called out for Charb – Stéphane Charbonnier, the director of Charlie Hebdo – to identify himself. They continued to shoot other people in the meeting.

Rey watched the murder of two fellow cartoonists, Georges Wolinski and Jean Cabu, from her hiding place under a desk. Reporter Laurent Léger also survived by hiding under a desk, while crime reporter Sigolène Vinson survived after one of the two killers told her he wouldn’t shoot her because she was a woman. That didn’t stop them from murdering Elsa Cayat, a psychoanalyst and columnist of Tunisian Jewish descent who was the only woman killed in that attack.

Others murdered five years ago in the attack include Franck Brinsolaro, Charb’s assigned bodyguard; Bernard Maris, editor, columnist, and economist; Mustapha Ourrad copy editor; Michel Renaud, a visiting travel writer; Ahmed Merabet, police officer killed outside of the offices; and cartoonists Philippe Honorè, Tignous and, of course, Charb himself.

After the Attack

The killers, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, escaped the offices and began running from the rapidly escalating manhunt. On January 9th of 2015, the brothers fled into an industrial group of buildings. Armed French police surrounded the compound and the siege last for nearly nine hours before the brothers ran out and opened fire onto the officers, successfully martyring themselves as was their desire. Across town an ally of the Kouachi brothers, Amedy Coulibaly, had taken hostages in a kosher supermarket, telling police he would kill his hostages if the brothers were harmed at the other siege. Coulibaly died within minutes of the Kouachi brothers, who he had reportedly been in contact with during the siege.

In December 2018, Peter Cherif was arrested by French authorities for playing a crucial role organizing the attacks on Charlie Hebdo. Cherif had been eluding French custody since 2011, when he fled right before being sentenced to five years in prison on unrelated terrorism charges.

Je Suis

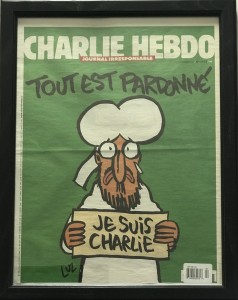

The next issue of Charlie Hebdo following the attack, 1178, which ran the now-iconic cover of Muhammad with a sign reading “Je suis Charlie,” was put together by the surviving Hebdo staff in the office of another French newspaper, Libèration. Normally an issue of Charlie Hebdo would have a print run of 60,000 copies. 1178 had a print run of 7.95 million copies, making it a record breaking publication for not just Charlie Hebdo but the entire nation of France.

The solidarity felt after the shooting was in no means absolute. There were many who participated in victim-blaming by accusing the staff of Charlie Hebdo of being responsible for their own violent deaths for publishing satire that some deemed offensive. There were massive protests in Yemen, Pakistan, Algeria, Senegal, Niger – where the protests were so violent that there were 10 fatalities – and many other places around the world.

134 Journalists have been murdered, including the ones who worked for Charlie Hebdo, since 2015. But 2019 was the safest year for journalists since 1992. That was following 2018 the deadliest year on record, with at least 34 confirmed murders including journalists killed in the mass shooting at The Capitol Gazette in Annapolis, Maryland and the murder and dismemberment of Washington Post reporter Jamal Khashoggi. Following that many media organizations tried to draw attention to this wave of violence, in hopes of creating change, and maybe it did. The nonprofit who tracks this violence, Committee to Protect Journalists, wrote about this recently,

The drop in murders comes amid unprecedented global attention on the issue of impunity in the killing of journalists, due largely to three recent cases that continue to reverberate. On October 16, 2017, the press in the European Union was dismayed when a car bomb killed a prominent anti-corruption blogger, Daphne Caruana Galizia, in Malta. Less than six months later, a second EU murder occurred with the shooting death in Slovakia of Ján Kuciak and his fiancée in their home; Kuciak had been reporting on the Italian mafia and alleged embezzlement of EU funds. Later in 2018, the murder and dismemberment of exiled Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul made headlines around the world.

It is impossible to know whether the high-profile nature of these murders and their consequences has deterred any would-be killers. CPJ has for several years documented a decline in the murders of journalists and a rise in self-censorship in traditionally dangerous places like Pakistan and Russia, where the lack of justice for past crimes has intimidated some away from critical reporting. Furthermore, those who wish to threaten the press have many tools besides murder at their disposal. The number of journalists imprisoned globally has remained at least 250 for four consecutive years, while journalists from Hong Kong to Miami have been subject to legal harassment, hacking, surveillance, and smear campaigns, CPJ research shows.

So the work isn’t done. Self-censorship for journalists in unsafe situations can’t be helped, so those who are safe must speak twice as loudly. We Are Charlie is not the cry of defeat by the media overwhelmed by the opposition, but rather a reminder of why we stand and fight against terrible odds. If We Are Charlie, then we must continue to commit time, energy, and column inches to the principles of free expression. And we can not wait for another deadly year, another terrorist attack, another murdered journalist to do so. Free expression saves lives.

Je Suis Charlie.