Pakistani political cartoonist Sabir Nazar is lucky. He’s currently in Washington, DC for a six-month fellowship at the National Endowment for Democracy, just as extremist attacks against journalists are ramping up in his home country. A few days ago he talked to Public Radio International’s Carol Hills about the difficulty of carving out a “very limited space to work” within the parameters defined by fundamentalists who increasingly control the Pakistani media through sheer intimidation.

In January, a few months before Nazar left for Washington, the Pakistani Taliban shot and killed three reporters from Express Tribune TV, a network associated with the progressive newspaper that also employs Nazar. In the wake of the attack, the extremists got exactly what they wanted when the Express Tribune instituted a new editorial policy:

Henceforth, no criticism of militant groups or religious parties. No criticism of terrorist attacks. No criticism of the Pakistani army.

And don’t even think about commenting on Pakistan’s wide-ranging blasphemy law, something militants use to justify their attacks.

Nazar doesn’t blame the editor for prioritizing safety over reporting, but he also won’t change his work to fit the new rules. Instead he continues to create and submit cartoons as he always has throughout his 25-year career, leaving the decision of whether to publish each one up to the editor. He thinks it’s important for cartoons and other art forms to simply continue to exist in Pakistan, because he sees the country heading down the same road previously taken in Afghanistan:

Roadside billboards in Pakistan are often covered with black paint. Dancing and certain types of music are banned on college campuses. In his hometown of Peshawar, Nazar used to sit outside and draw. Now he can no longer do that because it’s considered un-Islamic.

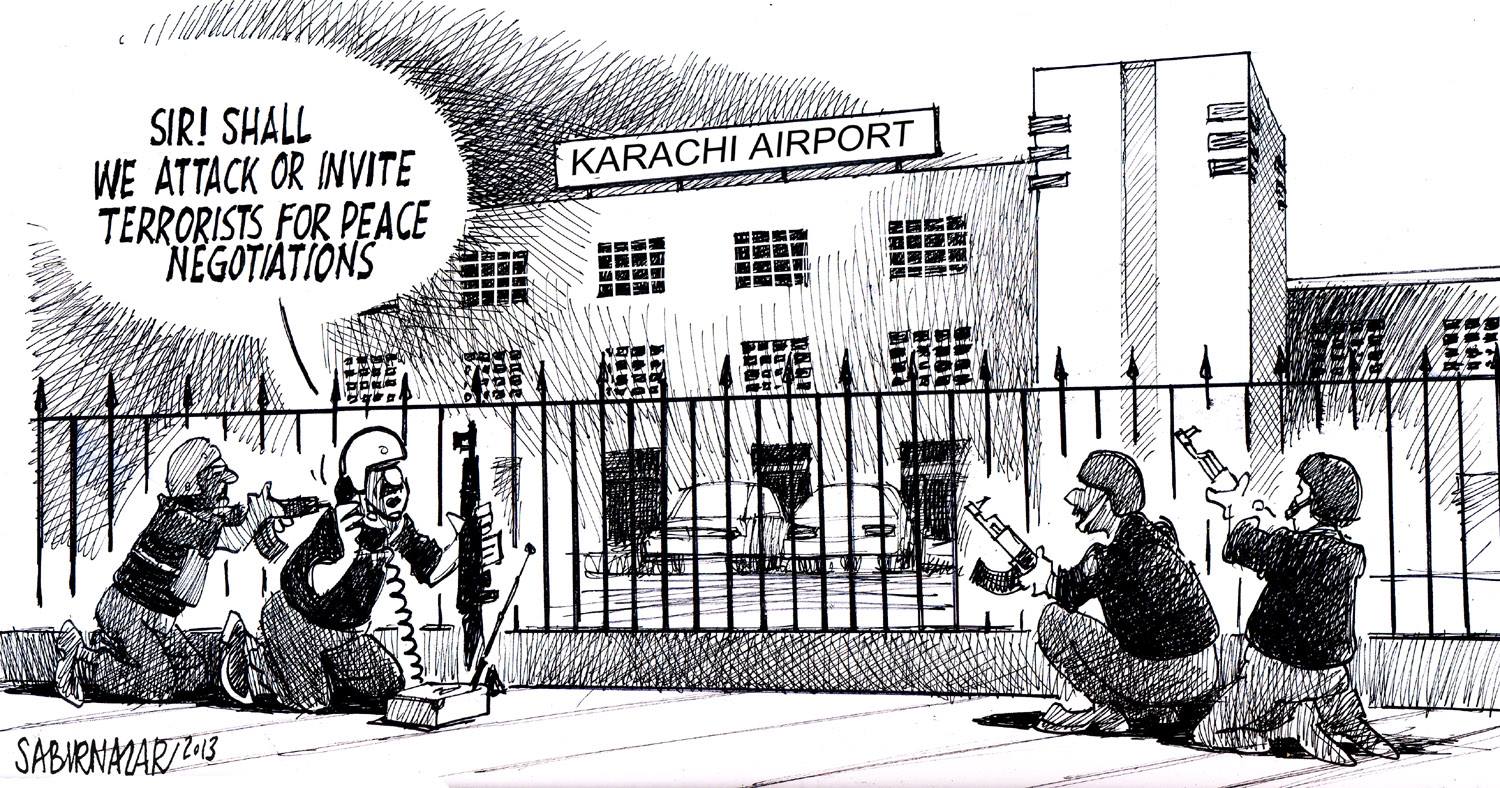

Even though he understands the reasoning behind the Express Tribune’s new policies, Nazar can’t resist testing the limits and logic of the paper’s self-censorship. The cartoon shown above is an example; it originally pertained to a 2013 attack on a hospital in the province of Baluchistan but was rejected by editors at the time. So when the Karachi airport was attacked earlier this month, Nazar simply changed the label on the building and resubmitted it. This time it was printed.

Nazar isn’t sure what he’ll do after his fellowship ends in August. Although he remains firmly convinced that the visual arts “have the ability to transcend religion, class and ethnicity,” he is frustrated to see so many forms of expression being effectively erased from Pakistan–not just by the extremists, but by all the regular people who concede to their demands.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs