Political cartoonist Xavier Bonilla, known as Bonil, has been charged with “socioeconomic discrimination” in his home country of Ecuador for a cartoon targeting Agustín “Tin” Delgado, a former professional soccer player who now sits on Ecuador’s legislative assembly.

Bonilla is best known for his outspoken and blunt political cartoons, which address several social and political issues within Ecuador. From his “insulting” cartoon of Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa (for which he narrowly avoided prosecution) to a controversial cartoon that depicted the raid of oil trade unionist and legislative adviser Fernando Villavicencio (a cartoon he was forced to revise within 72 hours of its publication), Bonil is no stranger to governmental censorship and he has been targeted by numerous social and political groups. Regardless, he has also become one of the most outspoken critics of the increased free speech violations in his home country.

A nominee of the 2015 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award, Bonil discussed the state of free speech in Ecuador in a recent interview with Index:

Freedom of expression here is permanently at risk. Cartoons represent a satirical and humorous take on all things that happen in public life. It’s part of debate in societies that are democratic, modern and civilized. The public identify with a cartoons through their humour, and often humour represents a chance for a sort of revenge. When there is an excessive power, the normal citizen can see in a cartoon, in comedy, or in a TV sketch, that they have been defended. Because the power has been ‘censored’, morally censored, because a cartoon is an imaginary triumph against the powerful, the abusive, the arrogant, the corrupt.

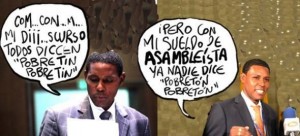

Bonil’s fervent belief in everyone’s fundamental right to freedom of expression was tested again last October when the Ecuadorian publication El Universo, which prints Bonil’s cartoons, ran the cartoon of Delgado. The publication quickly came under attack by both Afro-Ecuadorian social organizations and Ecuador’s central government. Offended parties claimed that the political cartoon, which portrays a stutter-ridden speech given by Delgado before the National Assembly last year, violates Articles 61 and 62 of Ecuador’s Law of Communication — specifically the section which prohibits the depiction of “discriminatory images.”

“How … with … m … my sp … eech, everyone says, ‘poor Tin, poor Tin’.… But now with my salary of an assemblyman, nobody says ‘poor Tin, poor Tin.'”

In response to the accusations, Bonil drew another cartoon that publicly apologized to Delgado for the offense, but legal action was still pursued. Bonil was originally charged with “racism,” but after the Charlie Hebdo attack, prosecutors changed the charge from “racism” to “socioeconomic discrimination.” A hearing was held against the artist by the Superintendency of Information and Communication (Supercom) on February 9, and on February 13 formal instructions were announced: El Universo would have to produce an apology to the “Afro-Ecuadorian social collective affected by the content” and the apology must appear in place of Bonil’s cartoon in the physical paper as well as on the publication’s digital front page for seven consecutive days. Bonil was issued a written warning:

[P]reparing him for the obligation to correct and improve his practices for the plain and efficient exercise of the right to communication, and compels him to abstain from repeating these acts that are at odds with the Law of Communication.

Bonil’s lawyer, a member of the Afro-Ecuadorian community, criticized the decision by Supercom:

You cannot fight against racial discrimination with a knee jerk decision like this. It is a small gesture that has been made with this resolution for the Afro community, making it so that an Afro public employee cannot be criticized. It is a tragic resolution and a terrible message for the national and international community.

In response to the accusations, sympathizers have used social media and public protests to express support for Bonil. Similar to messages of solidarity for Charlie Hebdo supporters have dubbed their movement #YoSoyBonil (“I am Bonil”).

Carlos Ponce, director of Latin America programs at Freedom House, “an independent watchdog organization dedicated to the expansion of freedom around the world,” recently said:

The ludicrous allegations against Bonil are the latest example of the Ecuadorian government’s ongoing effort to stifle the country’s independent media… Freedom House reiterates its call for the Ecuadorian government to respect the fundamental right to freedom of expression and end its politically motivated persecution of journalists like Bonil.

Furthermore, Victoria Ramirez, vice chairman of the Ecuador branch of EsLibertad, a worldwide network of students dedicated to personal liberty, also expressed her concerns over the recent governmental actions:

To punish a cartoonist is just like silencing a citizen. It is to prevent an individual from expressing his views peacefully…. Any kind of censorship, whether imposed in a coercive way, or self-imposed for fear of retaliation, should be reported, as it is a clear violation of freedom of expression.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Caitlin McCabe is an independent comics scholar who loves a good pre-code horror comic and the opportunity to spread her knowledge of the industry to those looking for a great story!