An Alabama librarian who stood up to segregationists and censors in 1959 is featured in a new stage play based on the battle over Garth Williams’ picture book The Rabbits’ Wedding. Some Alabamans, most notably State Senator E.O. Eddins, wanted the book banned because they said the story of a union between a black rabbit and a white rabbit promoted interracial marriage among humans.

An Alabama librarian who stood up to segregationists and censors in 1959 is featured in a new stage play based on the battle over Garth Williams’ picture book The Rabbits’ Wedding. Some Alabamans, most notably State Senator E.O. Eddins, wanted the book banned because they said the story of a union between a black rabbit and a white rabbit promoted interracial marriage among humans.

Playwright Kenneth Jones learned about the censorship fight when he read former Alabama State Librarian Emily Wheelock Reed’s obituary in the New York Times in 2000, instantly recognizing a story ripe for dramatization. The result is his play Alabama Story, which premiered in Salt Lake City last year and is featured in five regional productions in 2016, with more to come next year.

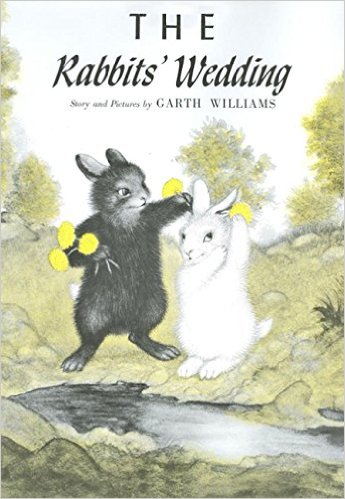

At the center of the controversy was Reed, who defended the presence of The Rabbits’ Wedding in the collection of the Alabama Public Library Service. Local public libraries around the state could borrow books from the centralized collection in order to loan them to their own patrons. The picture book by Garth Williams, perhaps best known for his illustrations in Charlotte’s Web and Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books, had drawn the ire of segregationists from the time it was published in 1958.

In Alabama, a censorship campaign by the Montgomery White Citizens Council drew the attention of Sen. Eddins, who threatened Reed’s job if she kept the book in the collection. She did compromise by moving The Rabbits’ Wedding from open stacks into a reserve area where librarians would have to request it specifically, but she staunchly refused to remove it altogether.

Williams was also nonplussed by the controversy over his book, noting that he drew the rabbits as black and white simply to make them easier for children to tell apart, and that they were inspired by traditional Chinese watercolors which juxtaposed black and white horses. In a statement issued by his publisher in 1959, Williams averred wryly that “I was completely unaware that animals with white fur, such as white polar bears and white dogs and white rabbits, were considered blood relations of white human beings.” He added that children would naturally understand the book better than adults “because it is only about a soft, furry love and has no hidden messages of hate.”

Later in 1959, Reed again drew the ire of the state legislature when she defended another book in her collection: Martin Luther King’s Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story, about the bus boycott in that city which had ended only three years before. King’s book was on an American Library Association list of notable books for 1959, which Reed distributed to local libraries just as she had done in prior years. Legislators again tried to pressure her to remove the book itself from the Public Library Service collection; when that failed, they introduced a bill that would have required the State Librarian to be Alabama-born and to hold a degree from either Auburn University or the University of Alabama. This would have disqualified Reed, who was born in Asheville, North Carolina and grew up in Indiana, graduating from Indiana University. But before she could be run out of the state, Reed left on her own terms in 1960 to take a job as coordinator of adult services for the Washington, DC public library system.

Just a few weeks after her death at the age of 89 in 2000, Emily Wheelock Reed was added to the Freedom to Read Foundation’s Roll of Honor. In its induction citation, the ALA-affiliated advocacy group praised her “remarkable stand…at a time and place where such action involved rare courage and personal and professional sacrifice.”

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2016 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.