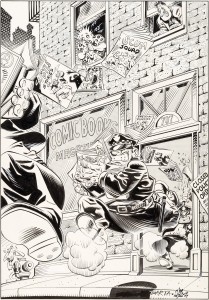

Thirty years ago today, the purchase of just 15 comic books would spark a chain of events that would ignite an ongoing fight for free expression across the entire industry. As CBLDF celebrates 30 years with a soon-to-end auction of original art from our very first benefit portfolio, we take a look back.

One young man, the manager of an unassuming comic book store in Lansing, Illinois, would be arrested and face charges for displaying obscene material. He life was shattered. For doing his job he was now facing prison time, fines, and the permanent stigma that came from being labeled a pornographer. With an outpouring of support from the comics community, he would receive funds toward his trial. What remained after his defense became the financial foundation for an organization that knew it must stand against threats to the First Amendment: the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

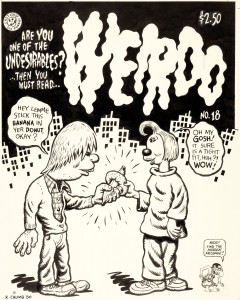

That young man was Michael Correa, the retail manager of comic book store Friendly Frank’s. On November 18, 1986, two officers entered the store and purchased comics from Correa, including Omaha the Cat Dancer, Heavy Metal, and Weirdo. Obviously, they didn’t like what they read, as six officers returned the next month to raid Friendly Frank’s and drag off Correa in handcuffs for the display of obscene materials.

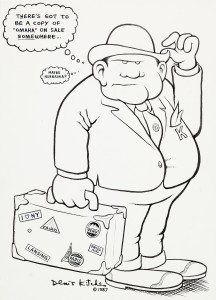

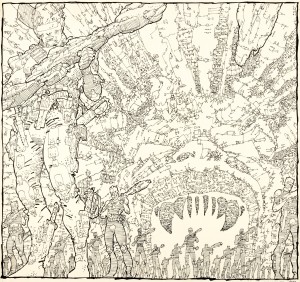

Shop owner Frank Mangiaracina took action, reaching out to other retailers and publishers for help, among them Denis Kitchen, publisher of Kitchen Sink Press. Together, they rallied a group of comics creators including Sergio Aragones, Hilary Barta, Reed Waller, Stephen Bissette, Bob Burden, Richard Corben, Robert Crumb, Howard Cruse, Will Eisner, Frank Miller, Mitch O’Connell and Don Simpson, and Eric Vincent to create a portfolio intended to raise money for Correa’s defense. In the aftermath of Correa’s defense, Kitchen founded the CBLDF and acted as its president for nearly 20 years until 2004, starting a legacy of liberty for the comics community.

While the anniversary of Correa’s traumatic arrest isn’t something to celebrate, the swift, generous actions of his community inspired the founding of the CBLDF — and protecting freedom, defending against unconstitutional legislation are worth celebrating. For the past three decades, comics creators, publishers, and fans continue to keep our legacy going, a legacy that began with seeing injustice and rallying to fight back.

We spoke with Kitchen about the impact of the arrest on Correa, the initial acts of generosity that provided for Correa’s defense, and the lasting legacy of this fateful day in comics history.

What can you tell me about the day of Michael’s arrest? How did you find out, and what were your and Michael’s reactions?

Kitchen: In December 1986 Frank Mangiaracina called me and said Michael had been busted by local Lansing cops. I was stunned, mainly because he hadn’t apparently done anything wrong, such as selling an inappropriate title to a minor. He was charged with displaying obscene material. What especially shocked me was the titles the cops found obscene: Heavy Metal, Crumb’s Weirdo, Omaha the Cat Dancer, and Bizarre Sex. A few weeks later they went in again and added Richard Corben’s The Bodyssey, Elektra: Assassin, Love & Rockets, and even Ms. Tree and ElfQuest to the list of charges. These comics, to be sure, contained erotic elements, though barely so in some cases.

He was this young guy, working in a comics shop–do you think he had any idea that his job would lead to the arrest?

Kitchen: I highly doubt it. Ordinarily managing a comics shop is a low-risk job.

Was there any warning that this could happen? Did you or Michael know these were potential consequences?

Kitchen: According to Frank there had been no warning, and Michael was shocked when he was arrested. No one had anticipated that selling a wide variety of comics to consenting adults would lead to consequences, including a fine and possible jail time.

How did you get involved? And what was it about this case that led to taking larger action?

Kitchen: I was the publisher of several of the titles, including Omaha the Cat Dancer by Reed Waller and Kate Worley. That long-running series, which began in Bizarre Sex, was effectively an erotic soap opera comic. There were long passages and entire issues without any sexual content, and when there was sexual content it was in a literary and plot context. Omaha had been widely praised by critics and fans, such as Neil Gaiman, and it had probably the highest female comics readership at the time. It was by no means obscene. So to be told that an important series like Omaha was illegal even to display in a neighboring state just boiled my inner furnace.

The next thing that pissed me off was when I read the local newspaper account of the bust. One of the Lansing police officers, Sgt. Jack Hoestra, said he found the busted comics not just obscene but products of the Devil himself. The Gary Post-Tribune quoted the officer saying, “Oh yes, there was absolutely a lot of satanic influence in the comics there. If you know what you’re looking for, you can see the satanic influence all over. Three-quarters of the rock groups today show satanic influence, and it’s all over the television.” It just totally floored me that police officers with this kind of world view could quickly ruin a business enterprise and a man’s career.

How did he decide to take legal action to defend himself? And how did he respond?

Kitchen: Michael didn’t personally take action. Frank hired a local attorney to defend Michael. The attorney assured them that it was an “open and shut case” that they would win easily. But in January 1988 Circuit Court Judge Paul Foxgrover found Michael guilty on thirteen charges brought against him. Michael was fined $750 and placed under one year court supervision. Michael, I think, was fearful that local headlines about obscenity had ruined his and his family’s reputation. He gave notice to Frank right after his conviction, and Frank said he spent an hour talking Michael out of quitting on the spot. It didn’t help that Judge, Foxgrover advised Michael from the bench that it was “inadvisable to keep working in the store.” In an ironic twist, Foxgrover himself plead guilty a few years later to forgery and stealing fines he imposed on defendants and was sentenced to six years in state prison.

This wasn’t the first time someone in comics had been prosecuted — but it was the first time the community organized to create a support network. What was it about Michael’s situation that inspired that?

Kitchen: Frank felt he and his attorney had the situation under control. But after Michael’s conviction, everything changed for me. It was a dangerous precedent for a retailer to be charged and convicted for simply displaying comic books and magazines that a fanatical cop found personally offensive. I felt something had to be done, starting with appealing the case. Since Frank had already paid out of pocket for legal help that may not have been competent, I felt it wasn’t fair for him to pay for a much more costly appeal. So I organized a portfolio to raise funds for what I called the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, not knowing at the time that it would become a permanent organization or a 501 (c) 3 non-profit. I quickly went through my Rolodex and contacted artists like Frank Miller, Robert Crumb, Reed Waller, and Richard Corben, whose titles had been part of the Friendly Frank’s bust. But I also reached out to artists who would likely never be busted, such as Will Eisner, Sergio Aragones, and others, including myself. Thirteen artists in all donated art for the plates, and each agreed to sign 250 of the most expensive edition. Kitchen Sink’s printer agreed to print the portfolio at cost, most distributors waived a mark-up, and fans reacted with enthusiasm: the 1,500 portfolios instantly sold out. I reached out to Burton Joseph, a prominent First Amendment attorney in Chicago, who agreed to take on the appeal. His services weren’t cheap, but the fund could pay him, and in November 1989 the Appellate Court in Chicago overruled Correa’s conviction.

I originally saw the fund-raising effort as a one time mission, to overturn the Friendly Frank’s case. But funds remained from the portfolio sales and other contributions, and industry support had been so positive at all levels—fans, retailers, publishers, creators—that I decided the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund should continue. Burt agreed to stay on retainer. I created a board of directors, including Frank and other early supporters. What we soon found is that there were cases similar to Michael and Frank’s in other parts of the country that would likely have been unknown outside their respective communities. But with the CBLDF as an umbrella organization and with growing national press the organization was able to defend many other retailers and other victims of First Amendment abuse. I’m extremely gratified to see that the organization, nearly three decades later, is stronger and more capable than ever.

You can bid on some of the original art from the benefit portfolio that Kitchen assembled to fun Correa’s defense, but act now! The auction ends around 11:45 a.m. PST! View the pieces and bid here.