Roberta Gregory uses dark humor to explore the modern world from a feminist perspective, and her groundbreaking work garners a broad spectrum of reactions, from veneration to outright rejection. During Emerald City Comicon she sat down with She Changed Comics editor Betsy Gomez to discuss her work and the role of women in the industry.

Roberta Gregory uses dark humor to explore the modern world from a feminist perspective, and her groundbreaking work garners a broad spectrum of reactions, from veneration to outright rejection. During Emerald City Comicon she sat down with She Changed Comics editor Betsy Gomez to discuss her work and the role of women in the industry.

Your father worked on comics for Gold Key and Disney — a lot of Donald Duck — so, it seems you were destined to become a comic book creator. Were you encouraged to make comics? Was there anything specific that put you on the path to making them?

Well, I like storytelling. Some of my earliest examples I still have of art when I was a child are pictures and captions describing them and little word balloons. And yeah, when I was a kid I would make little comics and staple them together and I’d sell them to my family members for 10 cents each. There was one that was a dollar, just because it had a lot of pages. I mean, I almost broke the stapler trying to staple it together. And then later on, I kinda grew up reading comics and when I was in high school I would kinda help my dad with dialogue. Like, he’d be writing a Daisy Duck story, and I’d kinda write some dialogue for him, so that was a lot of fun. I mean, I was uncredited. That was good training.

Your first strip was Feminist Funnies. In your bio, on your website, you wrote “I was happy to be living proof that feminists did have a sense of humor…” What drew you to humor in particular?

I’m not sure. I mean I’ve just always — most of the comics I’ve read were funny, like Sugar and Spice, Uncle Scrooge, a lot of the Disney comics. And I’m not really sure why I evolved a sense of humor, but it’s just, you know, I guess it’s just the way I look at the world. I mean, if I’m not laughing, I’d be crying and laughing’s more fun.

Did you ever get accused of not taking the cause seriously?

Yeah, I encountered some really dogmatic feminists and socialists — especially socialists, Marxists, in college. They were the most grim, humorless people I’ve ever encountered. So, I basically stuck around people who I enjoyed and most of the people that I enjoyed were funny, had a sense of humor, kind of looked at the world my way. And I tend to avoid people I don’t get along with. I mean I don’t see it as a challenge, I don’t see it like I can convert them, I just learned early on to stay away from toxic people.

You’ve worked on two seminal publications, Wimmen’s Comix and Gay Comix. Can you talk about how you got involved with each of those?

You’ve worked on two seminal publications, Wimmen’s Comix and Gay Comix. Can you talk about how you got involved with each of those?

Well, when I was in college, there were head shops in the neighborhood. Like, I moved off campus and they’re right off the street — this was Long Beach. I went to Cal State, Long Beach, and I lived two years in the dorms. And I actually started drawing comics for the campus humor paper Uncle Jam, published by Phil Yeh — he’s with Cartoonists Across America, still friends with him — and I drew the cover for the first issue, and I would draw funny satirical strips. I actually did the very first Frieda the Feminist strips. They’re full page strips that ran in Uncle Jam. And then I did strips for the Women’s Resource Center newsletter.

And this was right after I moved out of the dorms, and we went to head shops to look for comics and there were, like, lots of comics by women. There were Wimmen’s Comix. I think there was Tits & Clits, I think that has just been published by Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevli. This would have been like 1973, 1974. I think Trina [Robbins] had her Girl Fight Comics. And it was really exciting to see comics that were all kinds of styles.

I read comics when I was a kid and they almost all seemed to be done by men. The only woman whose work I think I’d ever seen was Marie Severin in Marvel Comics, and it just kinda seemed that women didn’t really do comics that were commercial that people read. I drew lots and lots of my own. I would draw these ongoing stories, like a science fiction story, a satirical super hero story, and I never thought they’d really get anywhere besides the back of the closet or whatever. And it was really exciting to see comics that were drawn by women. They had stories by women; they were sometimes real life stories. And they had all different styles of drawing, that’s what’s really exciting because a lot of these superhero comics the artists all looked like they were trying to draw like each other, and all of a sudden you could just draw anything, and I just found that really, really encouraging and enlightening.

How did your experience with Wimmen’s Comix compare to Gay Comix? Was there a difference?

Oh yeah, definitely. Wimmen’s Comix was really competitive. They came out I think once or twice a year, and they’d say “you can have a two-page story or so. Maybe a one-page story.” There seemed to be this big scramble for pages because they had a lot of contributors. There were probably at least ten to twelve different contributors for each comic, so that made your page count kind of low. And then when Gay Comix started, Howard Cruse, who was the first editor, said he wanted equal representation from men and women, and I was about the only woman back then doing LGBT comics. So, I could do long stories. I didn’t have to squeeze everything into two pages. I could actually have stories that sort of developed and had a middle and had an ending. And I had a lot of fun with Gay Comix. I definitely think that’s my much better work compared to Wimmen’s Comix.

When you were getting into comics, when you were working with Wimmen’s Comix and Gay Comix, who were some of the people who inspired and supported you as you were developing your craft?

When you were getting into comics, when you were working with Wimmen’s Comix and Gay Comix, who were some of the people who inspired and supported you as you were developing your craft?

Well I think the most inspiration and support I got was from Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevli because I went up to San Francisco to some comic book convention — I think in the early 70s — and kinda visited the San Francisco people and didn’t really fit in that well. But then I noticed that Nanny Goat Productions was in Laguna Beach, which was not very far south of where I was living. So, I drove down and visited them and they were just the nicest people: encouraging and had all kinds of suggestions about doing my own comic.

I think I had submitted one story to Wimmen’s Comix issue number four, and they have different editors because it’s a collective, so the editor back then was Shelby Sampson and she loved it. And then I did another story, which was, let’s see, it was kind of a proto-Dynamite Damsels, I think it was like my Doris character and her girlfriend and just kind of having a bad day. And then the next editor, whose name I don’t remember, said, “Well this was kind of like your other story,” and the only reason it was like my other story is it had lesbians in it, so I was thinking, “Okay, I don’t really like having a gatekeeper telling me that my work can’t get published,” so that’s when I got inspired to, “Why don’t I do my own comic?”

Dynamite Damsels, right?

Yeah. That was 1976. And that was a lot of encouragement from, let’s see, Lyn Chevli and Joyce Farmer and also Phil Yeh because he was starting to publish his own comics and zines and so forth, so he had some suggestions about where to get things printed. So, that was really fun. I mean, if I had known it was such a big job I probably wouldn’t have undertaken it back then but it was just “Hey, look at all these comics! I can do one!” And that kind of hearkened back to the little comics I’d put together, staple together, and sell, so–

Now you had some work in Tits & Clits, too, right?

Sure, yeah, like later on Tits & Clits turned into an anthology. The first couple issues were just Lyn Chevli and Joyce Farmer’s stories, and Lyn Chevli didn’t really care about doing comics that much; she was a sculptor rather than a two-dimensional artist. So, she kinda let go doing comics, and I think it was her idea to turn it into an anthology. I did some longer stories in Tits & Clits. In Wimmen’s Comix, after that point I think I did one or two one-page stories but I was working on other things back then, so Wimmen’s Comix wasn’t really my focus but there were tons and tons and tons of other women doing comics that could fill the pages so they didn’t miss me one bit.

Lyn and Joyce actually had a brush with the law, actually. Because Lynn’s old store—her old bookstore, Fahrenheit 451—was blasted for selling undergrounds.

Right, yeah.

And I know they had to hide all their comics in LA County, get them out of Orange County, because they were concerned they were going to get busted. Did you ever have concerns yourself that you might run into obscenity issues?

Not really, no. Like I said, if I had known I could’ve have gotten in trouble, I probably wouldn’t have done it, but it just really didn’t occur to me. I mean I was just sort of doing the stories I wanted to see and it was kind of “Wow, there are other people.” It was just heady just to think “Wow, somebody else might want to read my stories,” and I just really didn’t think that much about censorship.

You were making comics about LGBTQ issues in a very contentious time. LGBTQ individuals were being harassed by police officers on the streets of San Francisco, Harvey Milk was assassinated, the AIDS crisis was beginning and the government was largely ignoring it. How did that atmosphere influence your work? Did it have an impact on what you were doing?

Well, not terribly, actually. I didn’t really — like I said, it never really occurred to me that get “In trouble” for what I’m doing. I mean I was kind of used to “people either like me or they don’t like me,” so I realized early on I’m not put in this world to please everybody. But I was having a lot of fun with the Gay Comix stories because I was involved with the LGBT community, and I knew somebody that was an alcoholic so I wrote a story about an alcoholic. I had bisexual experiences, so I wrote a story where two women were kind of not terribly glued to their sexuality. I was living with a transgender person, so I did like a transgender themed story.

I had one where I had a character that came from some other dimension or some other place and had no gender at all and was kind of dealing with the obsession humans have with “are you one or the other?” And that ended up evolving into my Winging It graphic novel. That turned into my angel character from Winging It. I kinda get a notion, I create some characters, and then they just kind of evolve into other storylines like the Winging It characters — the angel and the goat character, they evolved into Artistic Licentiousness as the allegorical figures plaguing the protagonists. So, I always kinda had fun with that.

You began Naughty Bits in 1991, published by Fantagraphics. And with it, and you introduced the world to one of your most indelible characters, Bitchy Bitch. What was the inspiration for Bitchy Bitch? How do people, especially women, respond to the character?

You began Naughty Bits in 1991, published by Fantagraphics. And with it, and you introduced the world to one of your most indelible characters, Bitchy Bitch. What was the inspiration for Bitchy Bitch? How do people, especially women, respond to the character?

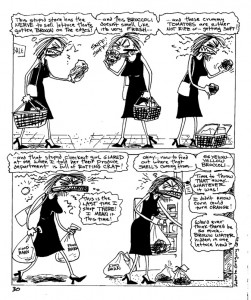

Well, let’s see… I think in the late ‘80s I was working on Winging It. That was my kind of tightly drawn, kind of William Blake-y graphic novel. And some of the other stories — I was working on Artistic Licentiousness just before that I think. I had this sort of tight drawing style and there was this sort of punk style of the late ‘80s that was sort of deliberately crudely drawn and people that were upset about the world and full of angst and so forth. A lot of that kind of got on my nerves cause I’ve always tried to make the most of things.

So, Bitchy Bitch — actually the very first appearance of her was in a comic I had drawn for a 1990 Graphic Story Monthly, in a story I did about the good and evil Robertas, which was kind of realistically drawn. The good Roberta was drawing kitty cat toons and the evil Roberta was drawing angst toons starring Bitchy Bitch that had this like scrawly character that was “Life sucks, I hate my life, waaah,” you know, “I wanna die,” and so forth. And then I think the two Robertas kill each other with X-Acto knives.

Anyway she seemed to be kind of a throwaway character but actually the most excitement came from my Crazy Bitches story. I had actually drawn that before Bitchy Bitch, and it came from working in Fantagraphics; I had moved up from California and was working in their paste-up department and shooting lots and lots of stats of the Complete Crumb and I was kinda thinking “Well, you know, is it the fact that he can get away with all of this violence against women is because it’s drawn in this cute style?” So, you know, I came up with this uncharacteristically scrawly, rubbery goofy style and had these women doing horrible things to a guy. And boy the shit hit the fan after that.

Anyway she seemed to be kind of a throwaway character but actually the most excitement came from my Crazy Bitches story. I had actually drawn that before Bitchy Bitch, and it came from working in Fantagraphics; I had moved up from California and was working in their paste-up department and shooting lots and lots of stats of the Complete Crumb and I was kinda thinking “Well, you know, is it the fact that he can get away with all of this violence against women is because it’s drawn in this cute style?” So, you know, I came up with this uncharacteristically scrawly, rubbery goofy style and had these women doing horrible things to a guy. And boy the shit hit the fan after that.

I bet the strip was funny.

Oh it was hilarious, yeah.

And cathartic actually.

Well, it was like I say, it was just sort of like, “Okay, you know, what if.” I think the inspiration was like this guy was reading Crumb, and his wife gets upset, and she’s, “Look what they’re doing,” and then they you know… they tie him up and they’re like kind of having sex with him. And the wife, she bites his dick off or something and I became the woman who draws men getting their penises cut off.

So it kind of proved my point. It was like, well people are just gonna be up in arms if a woman does something similar, you know, from a woman’s point of view even though it was so obviously not my style. But then the funny thing is, later on I started doing Naughty Bits stories. I think Naughty Bits was originally gonna be kind of a one shot of these rude little short stories and that’s it, and I think there was one story that one of the editors thought didn’t really work so I thought “Okay, my Bitchy character, let me put her on the date from hell, that’ll be — I’ll never want to see her again after that.” And then they wanted another issue, so I kind of gave her a background and they actually, you know, kinda sold okay. So, by issue three I figured “Okay,” because I’m really more of a novelist. I write long graphic novels, and I’ve got about three 130,000 word novels in progress, so I’m more of a novelist than like a gag cartoonist. So, I thought “Okay, well she’s got a life. There’s gotta be a reason she’s the way she is. She’s so unhappy.” And I just kinda started building her life, and before I knew it there were like 40 issues.

CBLDF deals with a lot of challenges to LGBTQ content. Why do you think LGBTQ literature in particular is challenged as frequently as it is?

Because it scares the hell out of people. I mean, it scares people with tiny minds and who are afraid of the unknown and maybe aren’t all that comfortable with their own notions of sexuality. Plus, some LGBT people are probably the last group of people [some] can still sort of hate.

All images (c) Roberta Gregory.

Interview transcribed by Charles Howitt.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2017 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!