The Comics Authority changed the face of comics forever. People are aware how horror comics were virtually abolished, romance comics were toned down, and jungle princesses forced to fade into the background, but they may be unaware how the CCA affected the mainstream superheroes of the time. I have previously written about how Superman was already governed by a stricter internal governance and, thus, was unchanged. Batman, on the other hand, fended off a homophobic public by getting a Batwoman named Kathy Kane to help establish heterosexuality, which, if you are reading current DC comics, is pretty ironic. But it is the third member of DC’s trinity that is the focus of this week’s posting — the Amazing Amazon known as Wonder Woman. The post-Code world was not a friendly place for the Amazon princess, who was already having a hard time dealing in the post WWII world.

The Comics Authority changed the face of comics forever. People are aware how horror comics were virtually abolished, romance comics were toned down, and jungle princesses forced to fade into the background, but they may be unaware how the CCA affected the mainstream superheroes of the time. I have previously written about how Superman was already governed by a stricter internal governance and, thus, was unchanged. Batman, on the other hand, fended off a homophobic public by getting a Batwoman named Kathy Kane to help establish heterosexuality, which, if you are reading current DC comics, is pretty ironic. But it is the third member of DC’s trinity that is the focus of this week’s posting — the Amazing Amazon known as Wonder Woman. The post-Code world was not a friendly place for the Amazon princess, who was already having a hard time dealing in the post WWII world.

Wonder Woman is easily most recognizable female superhero in comic book history. Since her debut in the early 1940s, Wonder Woman has served as a feminist role model for young ladies and also appealed to the largely male comic book audience at the time. She is arguably the first super-heroine to have her own comic book and her own self-titled book. And while Wonder Woman is not the first female superhero (I think that honor belongs to the Woman in Red), she is certainly the most influential. She was not merely a clone or female counterpart to some already established male hero (such as Hawkgirl , Batgirl, or Supergirl). Indeed, she was not even a girl but a full fledged woman. She also has had such an important influence that Wonder Woman comics are still popular today, more than 60 years after her comic book debut. The character has even inspired Wonder Woman Day, an annual charity event celebrated in Fleming, New Jersey, and Portland, Oregon, where money is raised to help bring awareness to domestic violence and give support to domestic violence shelters that provide critical help to those in need.

Wonder Woman is easily most recognizable female superhero in comic book history. Since her debut in the early 1940s, Wonder Woman has served as a feminist role model for young ladies and also appealed to the largely male comic book audience at the time. She is arguably the first super-heroine to have her own comic book and her own self-titled book. And while Wonder Woman is not the first female superhero (I think that honor belongs to the Woman in Red), she is certainly the most influential. She was not merely a clone or female counterpart to some already established male hero (such as Hawkgirl , Batgirl, or Supergirl). Indeed, she was not even a girl but a full fledged woman. She also has had such an important influence that Wonder Woman comics are still popular today, more than 60 years after her comic book debut. The character has even inspired Wonder Woman Day, an annual charity event celebrated in Fleming, New Jersey, and Portland, Oregon, where money is raised to help bring awareness to domestic violence and give support to domestic violence shelters that provide critical help to those in need.

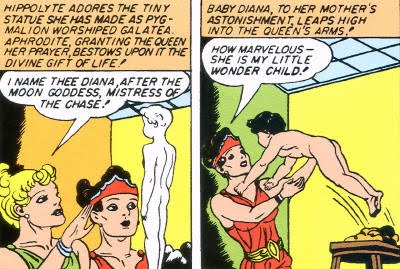

Until DC’s relaunch in the New 52, her origin was as mythic as the Greek Gods that serve as her patrons. The grief stricken Queen (known as Hippolyte in the Golden Age and Hippolyta since) of an reclusive female-only Amazon tribe molded a baby girl out of clay and begged her gods to bring the sculpture to life. The gods answered the Queen’s prayers, and the young girl leaps from the pedestal and into her “mother’s” waiting arms.

The Queen named the girl Diana (after the goddess of the hunt) and raised her as in the Amazon way. But then Steve Trevor crashes on the island and tells of the evils in the world (originally, the evil Axis of World War II and, in later retellings, the return if a vengeful god). Shocked by the news, the Amazons decide to hold a contest to choose who among them will represent the Amazons in man’s world. Diana defies her mother and enters the contest in secret. She wins. Bound by honor, the Queen lets her daughter leave her Amazon home (later named Paradise Island and Themyscyria). In man’s world, Diana dons a colorful red, white, and blue costume and, armed with a magic lasso (that compels people to tell the truth), an invisible plane, bullet proof bracelets, and her own fantastic abilities, becomes the super heroine known as Wonder Woman.

The Queen named the girl Diana (after the goddess of the hunt) and raised her as in the Amazon way. But then Steve Trevor crashes on the island and tells of the evils in the world (originally, the evil Axis of World War II and, in later retellings, the return if a vengeful god). Shocked by the news, the Amazons decide to hold a contest to choose who among them will represent the Amazons in man’s world. Diana defies her mother and enters the contest in secret. She wins. Bound by honor, the Queen lets her daughter leave her Amazon home (later named Paradise Island and Themyscyria). In man’s world, Diana dons a colorful red, white, and blue costume and, armed with a magic lasso (that compels people to tell the truth), an invisible plane, bullet proof bracelets, and her own fantastic abilities, becomes the super heroine known as Wonder Woman.

The real origin behind Wonder Woman’s creation is much more interesting.

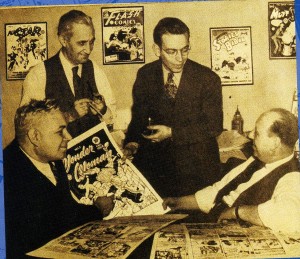

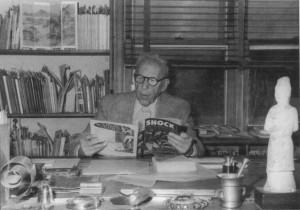

Wonder Woman was created by Dr. William Moulton Marston, a Harvard-trained psychologist with a law degree and a Ph.D. in psychology. He wrote extensively about the “systolic blood pressure symptoms of deception,” which is a fancy way of saying he invented the lie detector test. He would later create a perfect version of his famous lie detector in Wonder Woman’s lasso, which compelled people to tell the truth.

Wonder Woman was created by Dr. William Moulton Marston, a Harvard-trained psychologist with a law degree and a Ph.D. in psychology. He wrote extensively about the “systolic blood pressure symptoms of deception,” which is a fancy way of saying he invented the lie detector test. He would later create a perfect version of his famous lie detector in Wonder Woman’s lasso, which compelled people to tell the truth.

Marston was also a feminist. In a 1937 interview with the New York Times, he stated, “women would take over the rule of the country, politically and economically.” He believed that women were superior to men because they were not as violent or greedy as the male sex. He predicted that, in the next 100 years, the world would become a matriarchy.

As Les Daniels explains in Wonder Woman: The Complete History:

As Les Daniels explains in Wonder Woman: The Complete History:

Marston believed women were less susceptible than men to the negative traits of aggression and acquisitiveness, and could come to control the comparatively unruly male sex by alluring…. In short, he was convinced that as political and economic equality became a reality, women could and would use sexual enslavement to achieve dominance over men, who would happily submit to their loving authority.

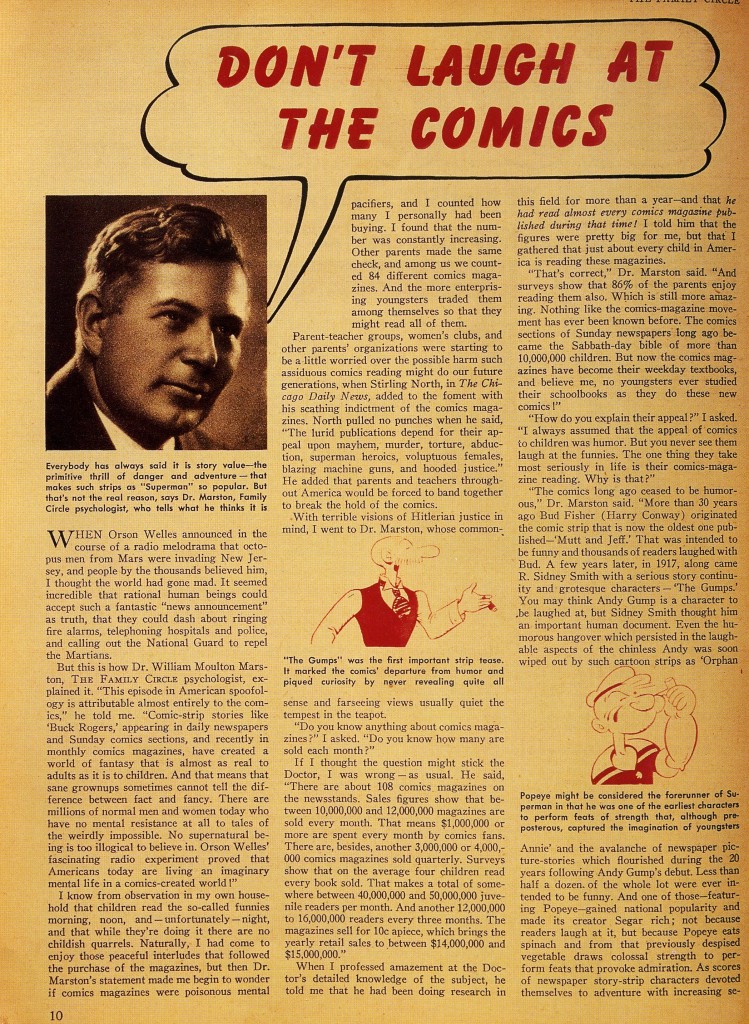

But Marston also knew a thing or two about comics. On October 25, 1940, Marston was interviewed in The Family Circle about the effect of comic books on society in an article entitled “Don’t Laugh at the Comics.” As a result of this article, MC Gaines hired him to be on the Editorial Advisory Board for the Detective Comics and All American lines. In the 1940s, the predecessors to DC Comics regularly hired educational consultants to ensure that the books were appropriate for their younger readers.

Through his work on the Advisory Board, Marston discovered a lack of female role models. Marston later wrote about his views on the board,

Among other recommendations which I made for better comics continuities was a suggestion that America’s woman of tomorrow should be made the hero of a new type of comic strip. By this I mean a character with all the allure of an attractive woman but with the strength also of a powerful man.

He expanded on this in a 1943 issue of The American Scholar. Marston said:

Not even girls want to be girls so long as our feminine archetype lacks force, strength, and power, not wanting to be girls, they don’t want to be tender, submissive, peace-loving as good women are. Women’s strong qualities have become despised because of their weakness. The obvious remedy is to create a feminine character with all the strength of Superman plus all the allure of a good and beautiful woman.

What came next is a bit of mystery. According to the Fall 2001 issue of the Boston University Alumni Magazine, it was Marston’s wife Elizabeth’s idea to create a female superhero:

William Moulton Marston, a psychologist already famous for inventing the polygraph (forerunner to the magic lasso), struck upon an idea for a new kind of superhero, one who would triumph not with fists or firepower, but with love. “Fine,” said [his wife] Elizabeth. “But make her a woman.”

In another version, Marston had always intended to create a female heroine in an attempt to expand and explain his vision of female superiority. Marston’s superheroine would serve as a female role model of sorts. He introduced the idea to MC Gaines, who was intrigued by the concept and told Marston that he could create a female comic book hero — a “Wonder Woman.” Only after he was given the go-ahead, did Marston develop Wonder Woman with his wife Elizabeth.

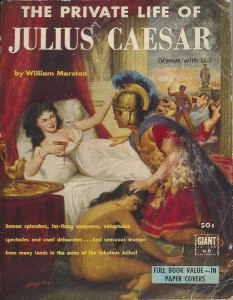

In fact, Wonder Woman was not Marston’s first publication to attempt to use popular culture to spread his views on sexism. His first effort was a 1932 novel called Venus With Us, a sexcapade starring Julius Caesar and a lot of strong women. Marston followed Venus with a few more mainstream books along with a large volume of scholarly works, but nothing ever achieved anywhere near the success of Wonder Woman.

In all versions of the Wonder Woman story, Marston used his own and Gaines’ middle names to create the pseudonym, “Charles Moulton.” His true identity was revealed in the summer of 1942 in an news release from All American Issued to coincide with the publication of Wonder Woman’s solo series, where he was identified as “Dr. William Moulton Marston, internationally famous psychologist.”

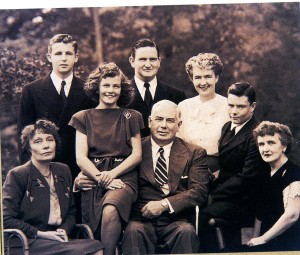

It is pretty clear that the inspiration for Diana came from both Marston’s wife, Elizabeth (Sadie) Holloway Marston (left), who Marston believed to be a model of that era’s unconventional, liberated woman and Olive Byrne (right), one of Marston’s students who lived with the Marstons in a relationship she described as a polygamous / polyamorous. It is also probably worth noting that Byrne wrote (under the name Olive Richard) The Family Circle article that got Marston his job on the DC Editorial Advisory Board and that she wore bracelets of submission that were very similar to those worn by Wonder Woman.

It is pretty clear that the inspiration for Diana came from both Marston’s wife, Elizabeth (Sadie) Holloway Marston (left), who Marston believed to be a model of that era’s unconventional, liberated woman and Olive Byrne (right), one of Marston’s students who lived with the Marstons in a relationship she described as a polygamous / polyamorous. It is also probably worth noting that Byrne wrote (under the name Olive Richard) The Family Circle article that got Marston his job on the DC Editorial Advisory Board and that she wore bracelets of submission that were very similar to those worn by Wonder Woman.

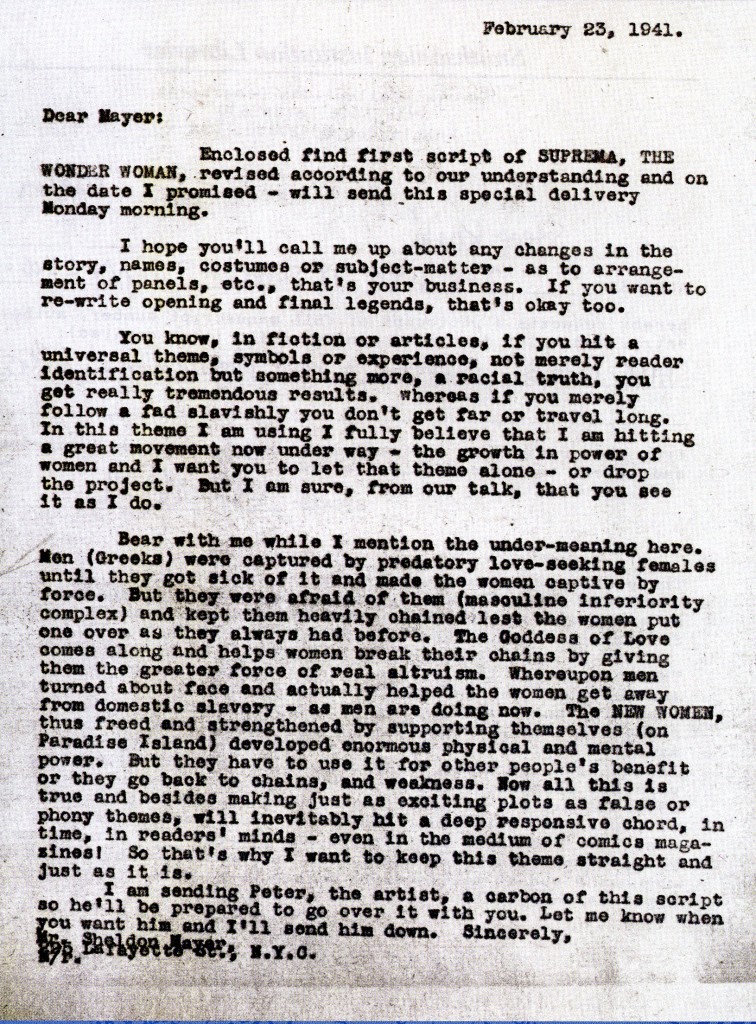

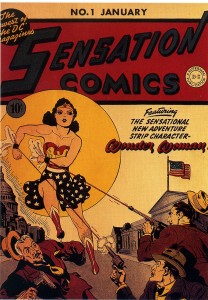

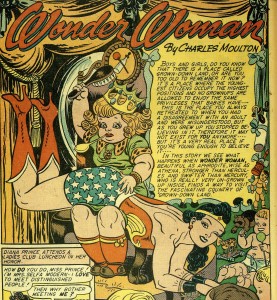

Marston had originally intended to call the character Suprema, the Wonder Woman. But by the time she appeared in an in an 8-page insert story in All Star Comics #8 (December 1941), editor Sheldon Mayer had shortened it to Wonder Woman. The insert story was included in the issue to test readers’ interest in a Wonder Woman concept. It obviously generated enough positive fan response since Wonder Woman became the lead feature in the Sensation Comics anthology title starting from issue #1. (I should add, as perhaps a sign of the times, that Wonder Woman would return to All Star Comics starting from issue #11 as a member of the Justice Society. But she was only allowed to serve as the group’s secretary even though she was selling more issues than the male JSAers.)

The art on Wonder Woman’s early adventures was drawn by an 61 year old artist named Harry G. Peter. Peter’s style was not as sophisticated as other artists at the time. Mike Madrid, in his book Supergirls explains:

[Peter’s] unique, often bizarre drawing style has been likened to woodcuts. He drew Wonder Woman with a shapely athletic figure, but not an exceptionally sexy one. She wasn’t especially busty, and her face had bee-stung lips of a 1920s flapper. All of this made sense for a comic book heroine who was meant to appeal to young girls, not to titillate men. Wonder Woman was radiant, confident, and inspiring, but not as luscious as a Hollywood starlet or a Vargas Girl pinup.

Editor Sheldon Mayer did not like the art. He explained in an interview with Les Daniels, “There were a lot of things Peter did that verged on the grotesque.” Mayer originally tried have Peter replaced, but the older artist’s simplistic style appealed to the academically trained Marston. Peter outlasted both Marston and Mayer and drew the book until his death in 1958.

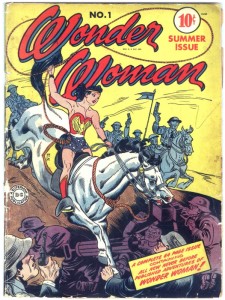

The early Wonder Woman stories featured World War II adventures. And like many women at home, who joined the workforce to replace the men who went to war, Wonder Woman joined the workforce that fought oversees. She frequently fought the Axis military forces, as well as an assortment of supervillains. Proving himself as a master manipulator, Marston was using patriotism to promote feminism (which is even more interesting when you consider this patriotic symbol of America was a Greek Pagan woman wearing an American flag themed bathing suit). During this period, the character of Wonder Woman was strong and powerful but she still remained tender and peace-loving. Wonder Woman became the voice of the female gender and an inspiration to young girls.

The early Wonder Woman stories featured World War II adventures. And like many women at home, who joined the workforce to replace the men who went to war, Wonder Woman joined the workforce that fought oversees. She frequently fought the Axis military forces, as well as an assortment of supervillains. Proving himself as a master manipulator, Marston was using patriotism to promote feminism (which is even more interesting when you consider this patriotic symbol of America was a Greek Pagan woman wearing an American flag themed bathing suit). During this period, the character of Wonder Woman was strong and powerful but she still remained tender and peace-loving. Wonder Woman became the voice of the female gender and an inspiration to young girls.

As Danny Fingeroth explains in his book, Superman on the Couch:

Wonder Woman was Rosie the Riveter writ large. Like Rosie, she had power — Rosie could hold the riveting bin, no mean feat in itself. But, Rosie also had the skill — whether self taught, taught by the male riveter, or another female riveter — to use the tool skillfully. Wonder Woman — like Rosie — took her power and skill, and it to, literally and figuratively, empower herself along with her readers, both female and male.

However, after the war, things were different. First, Marston died in 1947 and without his powerful feminine message, Wonder Woman became less powerful — her character changed to one less determined. Under new writer Robert Kanigher, Wonder Woman became less of a reformer and feminist and more of a traditional superhero.

Second, with the end of the war, Wonder Woman also suffered from a lack of purpose and post-war role of women. Madrid writes:

After the war, Wonder Woman’s future became cloudier. Rosie the Riveter was done working in the war plant, and was going back to making pies for her men folk. The Axis had been beaten, so what would Wonder Woman’s next mission be? …Wonder Woman became less interested in the welfare of her fellow women, and more in keeping Steve happy.

* * *

Wonder Woman was a pariah. Wonder Woman was never allowed to play with the boys, and had to stay on her side of the sandbox. The 1950s were not very kind to the Amazon Princess, as was the case for a lot of American women.

But, post-war apathy wasn’t the Amazon’s only enemy. She, along with her fellow comic heroes, were also under attack by waning public opinion and misconceptions about their effect on the increasing problem of juvenile delinquency. It should not surprising that Wonder Woman’s most staunch critic was Fredrick Wertham.

But, post-war apathy wasn’t the Amazon’s only enemy. She, along with her fellow comic heroes, were also under attack by waning public opinion and misconceptions about their effect on the increasing problem of juvenile delinquency. It should not surprising that Wonder Woman’s most staunch critic was Fredrick Wertham.

Wertham, the psychologist most blamed for inciting the crisis that decimated the comics industry, had a special venom for DC Comics’ trinity of superheroes. (“This Superman-Batman-Wonder Woman group is a special form of crime comics.”) Superman was a fascist, Batman was gay, and Wonder Woman was a sadomasochistic lesbian. In Seduction of the Innocent, Wertham singles out Wonder Woman as “a crime comic which we have found to be one of the most harmful.” He wrote:

The Lesbian counterpart of Batman may be found in the stories of Wonder Woman and Black Cat. The homosexual connotation of the Wonder Woman type of story is psychologically unmistakable. The Psychiatric Quarterly deplored in an editorial the “appearance of an eminent child therapist as the implied endorser of a series…which portrays extremely sadistic hatred of all males in a framework which is plainly Lesbian.”

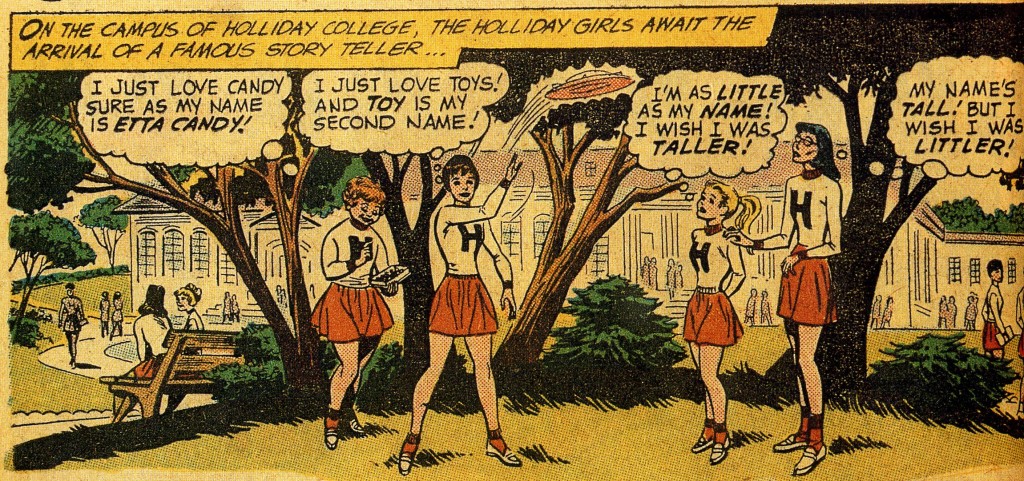

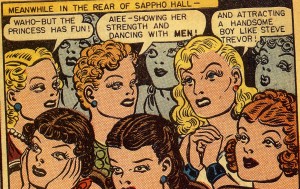

For boys, Wonder Woman is a frightening image. For girls she is a morbid ideal. Where Batman is anti-feminine, the attractive Wonder Woman and her counterparts are definitely anti-masculine. Wonder Woman has her own female following. They are all continuously being threatened, captured, almost put to death. There is a great deal of mutual rescuing, the same type of rescue fantasies as in Batman. Her followers are the “Holliday Girls,” i.e. the holiday girls, the gay party girls, the gay girls. Wonder Woman refers to them as “my girls.” Their attitude about death and murder is a mixture of the callousness of crime comics with the coyness of sweet little girls. When one of the Holliday girls is thought to have drowned through the machinations of male enemies, one of them says: “Honest, I’d give the last piece of candy in the world to bring her back!” In a typical story, Wonder Woman is involved in adventures with another girl, a princess, who talks repeatedly about “those wicked men.”

It should be mentioned that, Wertham’s accusations aside, the Holliday Girls, a group of 100 college girls (who had been long absent from the comics by the time Seduction came out) were as heterosexual as Robin, the Boy Wonder (Wertham’s other favorite target). In reality, the younger Holliday Girls (like Robin) served as stand-ins for the comic readers, with the adult superhero serving as surrogates for many of the readers’ absent parental figures, who were off fighting a war. The Holliday Girls also were almost the only example of comic supporting cast that provide positive female role models at the time. These girls banded together to fight oppression and relied on themselves and their sisters (as opposed to the damsels in distress present in other books) for their rescue.

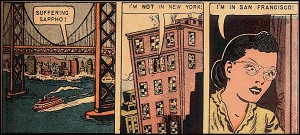

Marston also probably encourage these homosexual comparisons and accusations of lesbian overtones by having Wonder Woman’s favorite catch phrase be “Suffering Sappho!” Sappho was a female poet from the Greek island of Lesbos. It should be noted that this catch phrase appeared long before Wertham began his crusade and continued well after it. (Although a later writer, Kanigher, felt compelled to have Wonder Woman, in issue #132, clarify that the catch phrase originated from the fact that “Sappho was so sensitive she couldn’t stand suffering in any form.” Most likely, the phrase was one of Marston’s inside jokes that Wertham didn’t get like the use of Sappho Hall.

In addition to homophobia, Wertham also feared that Wonder Woman (like Superman) portrayed society and government as impotent. He wrote:

In one story a foreign-looking scientist starts a green-shirt movement. Several boys told me that they thought he looked like Einstein. No person and no democratic agency can stop him. It requires the female superman, Wonder Woman.

There are two very interesting things to point out about Wertham’s comments.

First, Wertham and Marston were contemporaries in the same field. They also both agreed on the power of comics. For example Wertham stated, in an article in the March 27, 1948, issue of Collier’s called “It’s Still Murder: What Parents Still Don’t Know About Comics Books” :

The comic books, in intent and effect, are demoralizing the morals of youth. They are sexually aggressive in an abnormal way. They make violence alluring and cruelty heroic. They are not educational but stultifying.

* * *

We do not maintain that comic books automatically cause delinquency in every child reader. But we find that comic-book reading was a distinct influencing factor in the case of every single delinquent or disturbed child we studied

Compare this to Marsten’s views published in the 1943 issue of The American Scholar:

It is the form of comics-story telling, “artistic” or not, that constitutes the crucial factor in putting over this Universal appeal. The potency of the picture story is not a matter of modern theory but of anciently established truth. It’s too Bradford us “literary” enthusiasts, but it’s the truth nevertheless — pictures tell any story more effectively than words.

And he states in The Family Circle article:

The comics sections of Sunday newspapers long ago became the Sabbath-day bible of more than 10,000,000 children. But now the comics magazine have become their weekday textbooks, and believe me, no youngsters ever studied their schoolbooks as they do these new comics.

Despite these similarities, the two doctors had very different approaches on how to handle this influential new medium. Wertham was doomsaying destructionist who sought to wipe out the comics industry before the medium could corrupt our youth (“The comic-book publishers, racketeers of the spirit, have corrupted children in the past, they are corrupting them right now, and they will continue to corrupt them unless we legally prevent it.”). Marston was an opportunistic manipulator who sought to use comics as a weapon to help improve society (“If Children will read comics, why isn’t advisable to give them something constructive to read?”).

The two doctors also had very different views about women’s roles in society. Wertham accuses Wonder Woman of being a poor role model and stated that Wonder Woman was giving little girls the “wrong ideas” about a woman’s place in society. In describing a delinquent girl named “Edith,” Wertham writes:

What goes on in the mind of such a girl? Where does the rationalization come from that permits her to act against her better impulses? Her ideal was Wonder Woman. Here was a morbid model in action. For years her reading had consisted of comic books. There was no question but that this girl lived under difficult social circumstances. But she was prevented from rising above them by the specific corruption of her character development by comic-book seduction. The woman in her had succumbed to Wonder Woman. By reading many comic books the decent but tempted child has the moral props taken from under him. The antisocial suggestions from comic books reach children in their leisure time, when they are alone, when their defenses are down.

Wertham also goes as far to consider the concept of a female superhero as ludicrous as the concept of funny animal super hero. (“Just as there are Wonder Women there are wonder animals, like Wonder Ducks.”) This is very different from Marston’s views of feminine superiority. And it is here that Wertham takes Marston’s view head on in Seduction of The Innocent and calls out his fellow psychologist:

The prototype of the super-she with “advanced femininity” is Wonder Woman, also endorsed by this same expert. Wonder Woman is not the natural daughter of a natural mother, nor was she born like Athena from the head of Zeus. She was concocted on a sales formula. Her originator, a psychologist retained by the industry, has described it: “Who wants to be a girl? And that’s the point. Not even girls want to be girls. . . The obvious remedy is to create a feminine character with all the strength of Superman. . . . Give (men) an alluring woman stronger than themselves to submit to and they’ll be proud to become her willing slaves.” Neither folklore nor normal sexuality, nor books for children, come about this way. If it were possible to translate a cardboard figure like Wonder Woman into life, every normal-minded young man would know there is something wrong with her.

So, what was Marston’s response?

He had none.

Seduction of the Innocent was printed in 1954, years after Marston’s death.

The second major thing that should be noticed is that while Wertham’s views about Superman and Batman bordered on paranoid delusion, the good doctor wasn’t too far off in his assessment of Wonder Woman or her creator, Marston.

As alluded to above, Marston’s sexual ethics were based on a theory of gender characteristics that classed men as aggressive and conflict-oriented, and woman as “alluring” and submissive. Marston who was also openly interested in sexual bondage also claimed that his vision of women’s submissiveness was actually empowering. He believed that the evils of the world could be traced to the illusion of male domination over women and women, “who possessed twice as many love generating organs and endocrine mechanisms as the male” and wielded the force of love. He stated, in another family circle interview with “Olive Richards” entitled, “Our Women Are Our Future”:

As alluded to above, Marston’s sexual ethics were based on a theory of gender characteristics that classed men as aggressive and conflict-oriented, and woman as “alluring” and submissive. Marston who was also openly interested in sexual bondage also claimed that his vision of women’s submissiveness was actually empowering. He believed that the evils of the world could be traced to the illusion of male domination over women and women, “who possessed twice as many love generating organs and endocrine mechanisms as the male” and wielded the force of love. He stated, in another family circle interview with “Olive Richards” entitled, “Our Women Are Our Future”:

Frankly, Wonder Woman is psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world.”

* * *

Wonder Woman is actually a dramatized symbol of her sex. She’s true to life-true to the universal characteristics of women everywhere. Her magic lasso is merely a symbol of feminine charm, allure, oomph, attraction every woman man uses that power on people of both sexes whom she wants to, influence or control in any way. Instead of tossing a rope, the average woman tosses words, glances, gestures, laughter, and vivacious behavior. If her aim is accurate, she snares the attention of her would-be victim, man or woman, and proceeds to bind him or her with her charm.

* * *

No man wants to be freed by the girl who has caught him and no man has the slightest interest in tying up a girl who holds out her hands to be bound. If he takes her as his property, that’s a bad day for both of them. The man begins to use dominance, and that’s acutely painful for the woman captive. Wonder Woman and her sister Amazons have to wear heavy bracelets to remind them of what happens to a girl when she lets a man conquer her. The Amazons once surrendered to the charm of some handsome Greeks and what a mess they got themselves into. The Greeks put them in chains of the Hitler type, beat them, and made them work like horses in the fields. Aphrodite, goddess of love, finally freed these unhappy girls. But she laid down the rule that they must never surrender to a man for any reason. I know of no better advice to give modern women than this rule that Aphrodite gave the Amazon girls.

* * *

Of course, she may let the man think she’s helpless. My Wonder Woman often lets herself be tied into a bundle with chains as big as your arm. But in the end she easily snaps the chains. Women can do lots of things by letting men think they’re fettered when they’re not.

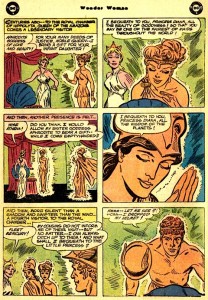

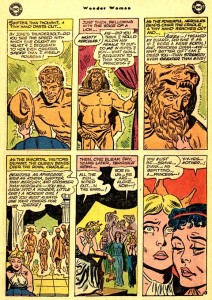

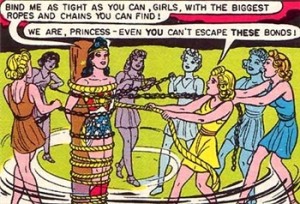

And his Wonder Woman certainly let herself be tied up. Gerard Jones, in Men of Tommorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book, provides a perfect example in his description of “The Battle for Womanhood” in Wonder Woman #5.

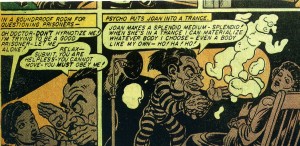

Every Wonder Woman story included at least one prominent scene — usually several — of someone bound. One story opens with a chained slave girl being berated by the god Mars, then proceeds to Doctor Psycho tying up a man and torturing him to death. Next, Psycho suspends his fiancee, Marva, by her wrists, hypnotized her, forces her to marry him, ties her to a chair, blindfolds her, and “uses her for occult experiments.” He puts her on display in a glass box, still blindfolded; Wonder Woman arrives but is conned into tying her to the chair again (“ow! Please don’t tie so tight!” “Why that isn’t half tight enough!”) and then, two pages later, induced into tying her up yet again (“Oh, I hate to be bound — can’t I please remain free?” “Certainly not, my dear! No woman can be trusted with freedom!”). Next the Amazon, in her secret identity as Diana Prince, helps manacle three office girls and strip them to their camisoles, panties, and garter belts. She discovers that her beloved Steve Trevor is locked in a cage, but in trying to rescue him, she’s electrocuted and manacled to a wall — at ankles, wrists, arms, and throat. She escapes, frees Steve, and bursts into a vault to find poor Marva blindfolded and shackled to a bed. In the end, a gang of sorority sisters echoes the “baby game” [a sorority hazing ritual where girls were forced to dress up as babies] of Dr. Marston’s early life as they chase Dr. Psycho to “give him a Lambda Beta treatment!” “Paddleup, sisters! Give ‘im the works!”

I should add that story ends with a typical Marston message as Marva exclaims “Submitting to a cruel husband’s domination has ruined my life! But what can a weak girl do?” Wonder Woman advises, “Get strong! earn your own living… fight for your country! Remember, the better you can fight the less you’ll have to!” While this is a noble message, it gets lost in all that bondage.

In fact, Les Daniels, in DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World’s Favorite Comic Book Heroes, estimates:

Wonder Woman’s adventures were increasingly dominated by images of female figures bound by ropes and chains. A short story published in 1942 featured fifteen separate panels depicting someone in bondage; a long story published in 1948, and apparently completed just before Marston’s death, contained no fewer than seventy-five bondage panels, many of the including multiple prisoners.

Even before Wertham’s tirades, Marston’s scripts had come under attack from both inside and outside the company. A review of correspondence between Marston and the powers that be at DC show the rising concern about Marston’s methods.

Josette Frank from the Child Study Association of American and member of DC Advisory Board, wrote that, “[Wonder Woman] does lay you open to considerable criticism from any such groups ours, partly on the basis of the woman’s costume (or lack of it), and partly on the basis of sadistic bits showing women chained, tortured, etc. I wish [MC Gaines] would consider these criticisms very seriously because the have come to me now from several sources.

Josette Frank from the Child Study Association of American and member of DC Advisory Board, wrote that, “[Wonder Woman] does lay you open to considerable criticism from any such groups ours, partly on the basis of the woman’s costume (or lack of it), and partly on the basis of sadistic bits showing women chained, tortured, etc. I wish [MC Gaines] would consider these criticisms very seriously because the have come to me now from several sources.

In response, Marston argued, “[Enjoyment of being subdued] is the one truly great contribution of my Wonder Woman strip to moral education of the young. The only hope for peace is to teach people who are full of pep and unbound force to enjoy being bound…women enjoy submission, being bound.”

Fellow Advisory Board member, Dr. Lauretta Bender (from Bellevue, where, ironically, she worked with Wertham, who was director of the Hospital’s Mental Hygiene Clinic) sided with Marston and believed that Wonder Woman did not tend towards masochism or sadism and that Marston’s experiment was clever.

W.W.D. Sones, an advisory member and professor of education from the University of Pennsylvania sided with Frank against Marston and wrote:

My impression confirmed those of Miss Frank that there was a considerable amount of chains and bonds, so much so that the bondage idea seemed to dominate the story. . . . I was not impressed with Dr. Marston’s argument; the social purpose which he claims is open to very serious objection.

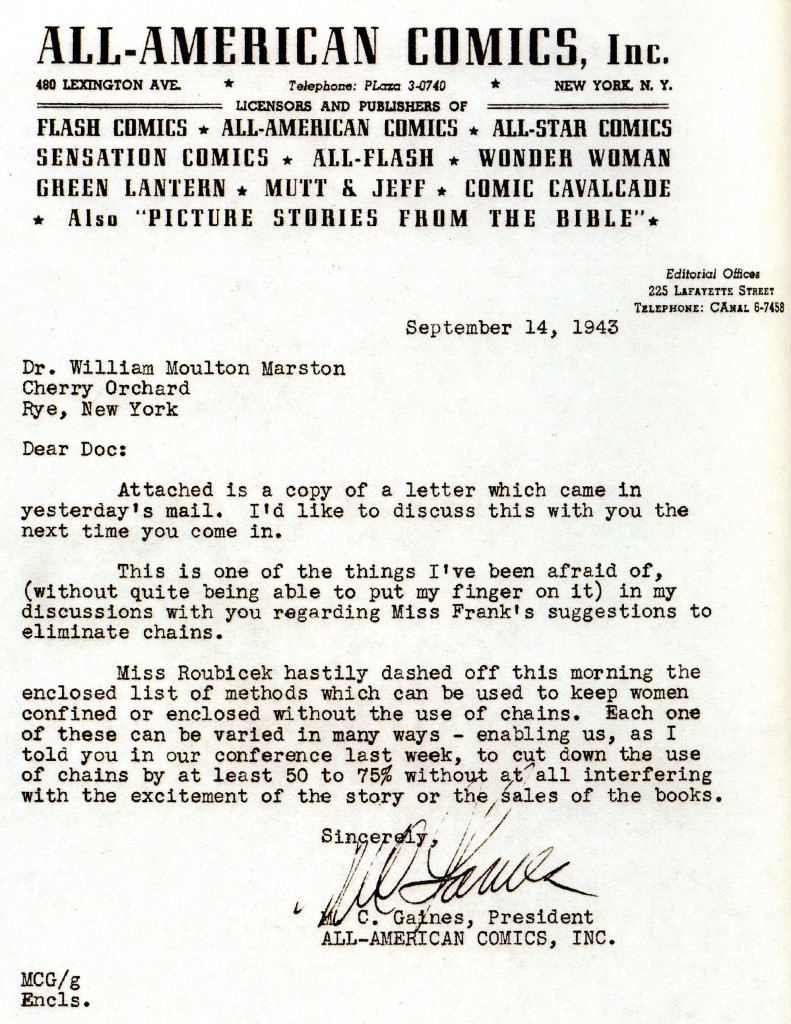

Things came to a head when Gaines received a letter from an Army sergeant who admitted that he derived immense erotic pleasure from the chained women in Wonder Woman. In response, Gaines sent the following letter to Marston:

Gaines ultimately decided that the bondage could stay (and asked it be disguised). Josette Frank asked to be removed from the advisory board and the internal conflict was resolved.

But the external conflicts still continued. For example, the National Organization for Decent Literature (NODL) formed by a committee of Catholic Bishops continued to keep Wonder Woman on its black list because of her costume. They wrote:

We see no reason why Wonder Woman should not be better covered, and there is less reason why women who fall under her influence should be running around in bathing suits.

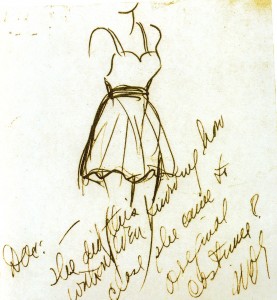

Apparently, in addition to coming up with “methods with which to keep women confined or enclosed without the use of chains,” Dorothy Roubicek was also tasked with this problem and drew a proposed, but never adopted, new costume for Wonder Woman.

Like his creation, Marston himself was a controversial figure. Louise Simonson, in DC Comics: Covergirls explains:

[Wonder Woman’s] creator was a man of paradoxical impulses. In many ways an idealist and a seeker of scientific truth, he was also a shameless manipulator of people’s perceptions. He was a visionary who believed in the equality (and in some ways, the superiority) of women. And yet his stories are filled with images of women in bondage. And, perhaps strangest of all, he was an intellectual who loved the new art form of comic books.

In his personal life, Marston had an affair with his graduate student and research assistant, Olive Byrne. When his wife Elizabeth discovered the affair, the marriage did not end. Rather, Olive moved in with the Marstons and the three developed a ménage a trois relationship. Olive and Elizabeth had two children each, all four fathered by Marston. Olive raised the children and Elizabeth worked to support the family.

In his personal life, Marston had an affair with his graduate student and research assistant, Olive Byrne. When his wife Elizabeth discovered the affair, the marriage did not end. Rather, Olive moved in with the Marstons and the three developed a ménage a trois relationship. Olive and Elizabeth had two children each, all four fathered by Marston. Olive raised the children and Elizabeth worked to support the family.

Mar ston was also apparently was convicted of fraud earlier in his life. The March 7, 1923, Bridge Port Telegraph Reports:

ston was also apparently was convicted of fraud earlier in his life. The March 7, 1923, Bridge Port Telegraph Reports:

Dr. Marston was arrested on a warrant charging use of the mails to defraud and was taken before United States Commissioner McDonald, who fixed the date of the hearing. He was indicted last November in Boston on complaint of a number of creditors who charged that as treasurer of the United Dress Goods, Inc., he misrepresented the financial condition of his firm and thus obtained considerable bills from them. Prominent among the complainants are A.D. Julliard & Co. and C. Bahnsen & Co. of New York. Another is his ex-furnace tender, of Boston, whom it is alleged he owes more than $100.

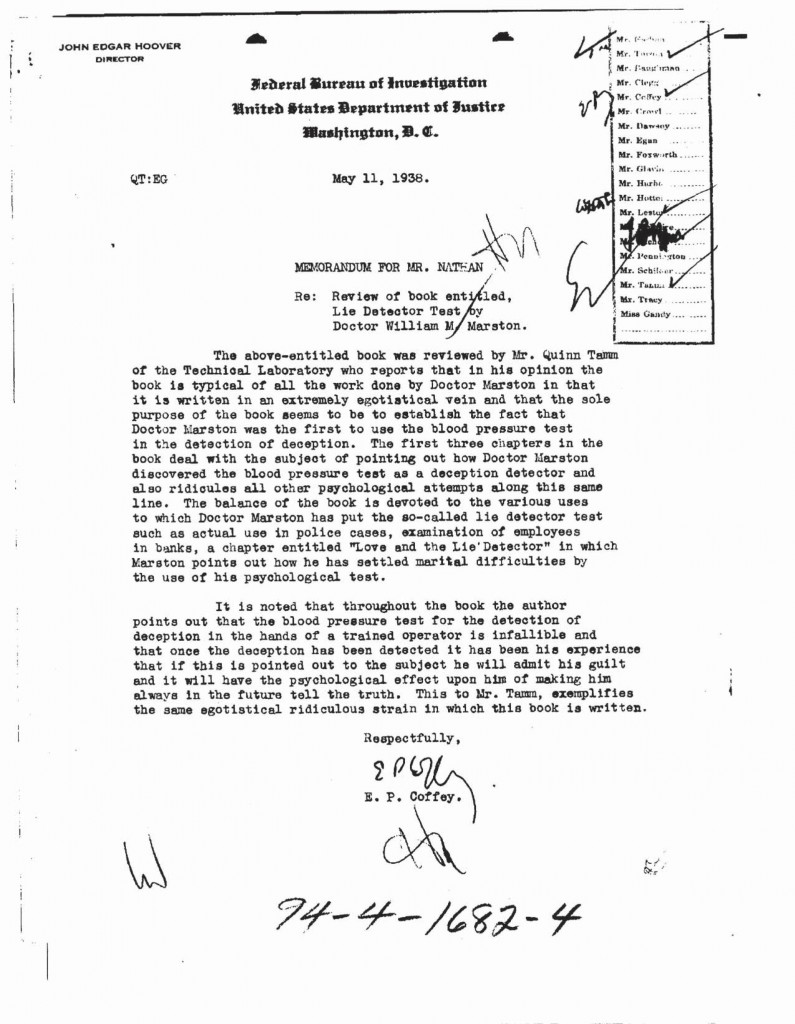

In my research, I discovered an FBI file on Marston (obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request). Two things jumped out. First, Marston sent a review copy of his lie detector book to the government and offered his services. The book was given to E.P. Coffey, head of the FBI’s Technical Laboratory. He wasn’t impressed, as the following memo shows:

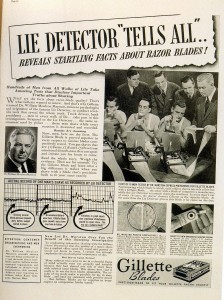

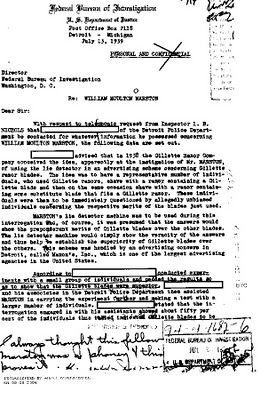

The file also contains an investigation into a marketing campaign, in which Marston affected the result of a lie detector test to show men liked Gilette razors. Of note, is the handwritten note that read, “I always thought this fellow Marston was a phony & this proves it!”

Wertham was certainly aware of most of this activity (as well as the strange home life situation between Marston, his wife, and his student.) Yet he did use any of the information to make his arguments. Wertham could have easily garnered more support for his views against Wonder Woman by highlighting the life and views of her creator beyond the vague comments above, which were made without even identifying Marston. Perhaps it was professional courtesy or just general sense of decency, but Wertham showed uncharacteristic restraint in discussing Marston’s lifestyle choices.

While Wertham’s attack did not result in the outlawing of comics, it did affect the comics industry in general and Wonder Woman in specific. In September 1954, The Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA) was formed in direct response to a widespread public concern over gory and horrific comic-book content. The CMAA created the Comics Code Authority, a self-policing “code of ethics and standards” for the industry.

While Wertham’s attack did not result in the outlawing of comics, it did affect the comics industry in general and Wonder Woman in specific. In September 1954, The Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA) was formed in direct response to a widespread public concern over gory and horrific comic-book content. The CMAA created the Comics Code Authority, a self-policing “code of ethics and standards” for the industry.

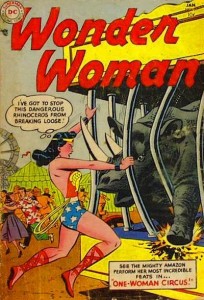

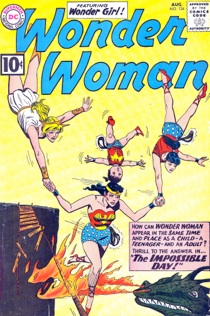

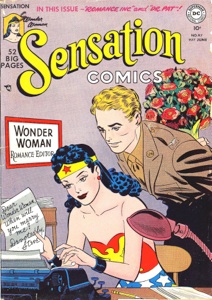

Under the comics code, Wonder Woman’s sexuality and feminism were far too controversial and were eliminated. Instead of the strong, self-sufficient woman Marston had conjured, the new Wonder Woman became a caricature of her former self. She transformed into a weak figure with no personality or wit. Denied her erotic and feminist history, she became a virginal, domesticated figure whose goal of fighting injustice was abandoned for marriage and shopping. Once strong and independent, Wonder Woman became more concerned with getting Steve Trevor (or, as can be seen below, Batman) to the altar.

The Comics Code also had a direct affect on Wonder Woman’s supporting cast and backstory. After the death of Peter, a new artist changed Wonder Woman’s look to make her slim, pretty, and girlish. Her mother also received a makeover, from a muscular brunette armored warrior into an elegant blonde beauty with a flowing white gown. More importantly, and forgotten by many fans, Wonder Woman’s origin was completely changed for a time to make it more Code friendly.

First, and foremost, the man-shunning Amazons were changed in an apparent attempt to promote the sanctity of marriage. The new Amazons were all happily married until their men were killed in war. The Amazons were then so grief-stricken they boarded a boat to Paradise Island far from war (translation: men and marriage were ok, war was not).

Also abolished was Marston’s concept that Diana was magically created from clay. Instead, the new origin was more like Walt Disney’s Sleeping Beauty film. The queen gives birth to her ordinary daughter (we know there is a father, but we don’t know who it is.) Then, like the fairies Flora, Fauna, and Merriweather, the Greek gods give the baby the gifts of strength, wisdom, speed, and beauty. As a result, Wonder Woman’s powers were derived from the Greek gods rather her highly trained Amazon mind. Interestingly, the rest of the origin is the same except that her charter is changed so that she no longer fights for the rights of women. This is interesting since Diana’s participation in the contest against her mother’s will would clearly have violated the Code which prohibited “disrespect for established authority” and required that “Respect for parents, the moral code, and for honorable behavior shall be fostered.”

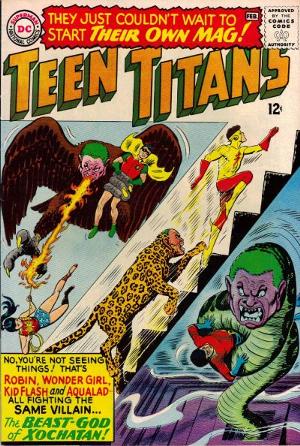

As a result of these changes, the stories in Wonder Woman grew increasingly more ludicrous. The world was introduced to Wonder Tot and Wonder Girl, who were younger versions of Wonder Woman, and then things became confusing when all three would team up as the Wonder Family. The feathered Bird-Boy and the amphibious Merman fought for the hand of a teenage Wonder Girl. In fact, a confused Bob Haney would have Wonder Girl join the Teen Titans (this Wonder Girl would later be retconned as Donna Troy). Readers also witnessed the birth of silly villains like Mouse Man, the Amoeba Man, and Egg Fu.

Perhaps the best way to demonstrate Wonder Woman’s fall from grace is to quote Mike Madrid’s Supergirls:

A 1965 story entitled, “I Married a Monster” shows how far Wonder Woman had deviated from her original incarnation. The Wonder Family is aghast when the Amazon princess agrees to marry the hideous, woman-hating beast Mr. Monster, thinking her love can redeem him. The Amazon’s love transforms the monster into a handsome prince, but his own bad nature has him green and ugly again in no time. As the hateful monster storms off in a huff, a tearful Wonder Woman thinks, “The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach! I’ll ask mother for recipes that will make the monster act like the dreamboat he became for a few moments!” Now let’s review. Once Wonder Woman’s mission was to save the world by ending war and violence, and teaching mankind about the power of love. The idea of her putting on an apron to whip up some spanakopita to win over a mean-spirited guy made it apparent how much of a shadow of her former self she had become.

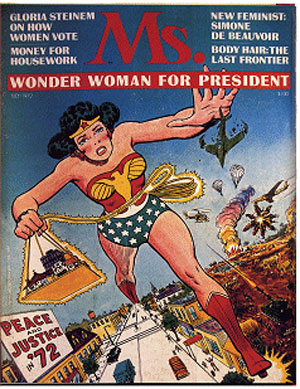

Marston’s Wonder Woman was gone, thoroughly destroyed by Fredrick Wertham, Seduction of the Innocent, and the Comics Code Authority. Thankfully, people still remembered her and would help Wonder Woman and her creators find their way back to essence of the character in comics as well as other mediums. The peaceful Amazon warrior was soon back on her mission to beat man’s world into submission with love.

One of those other mediums was television, where she was played by the amazing Lynda Carter. Ms. Carter has summed up the inspiration for her most famous role as follows:

Wonder Woman is to me — as she is to so many women of all ages — a symbol of all the glorious gifts that reside in the spirit of Woman. She is dashing and dazzling. Yet her true power and beauty come from within. The magic tools she brings to the fight — the bracelets, the lasso, the invisible plane — are only as good as her own ability, confidence, and courage to wield them. In that regard, perhaps she is not so different from you and me. We all show one part of ourselves to the world, while we hold close the ultimate power within us. Only when we trust in ourselves do we reach our fullest potential.

It is certainly a sentiment that Marston would be proud of. And one that could never have been fostered had Wertham succeeded in his scorched Earth attack on comics and free speech mandated in Seduction of the Innocent, published years after Marston’s death.

Of course, if Martson had been around to read Seduction, I’m sure he would have believed that Wertham could have been shown the light. All it would take was a good woman. Well a good woman woman and a lot of rope.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net/.

Wonder Woman, Superman, Batman, and associated characters (c) DC Comics.