It’s Valentine’s Day, so love is in the air. What better time to talk about the history of romance comics? After the war, when the sales of the superhero and crime comics began to wane, romance comics filled the gap. Soon, the market was filled with hundred of “love” titles. Of course, it didn’t take long for this new genre to come under fire and fall prey to the backlash against comics.

It’s Valentine’s Day, so love is in the air. What better time to talk about the history of romance comics? After the war, when the sales of the superhero and crime comics began to wane, romance comics filled the gap. Soon, the market was filled with hundred of “love” titles. Of course, it didn’t take long for this new genre to come under fire and fall prey to the backlash against comics.

The year was 1947. Harry Truman is President. Miracle on 34th Street opens in theaters. Jackie Robinson signs a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers, making him the first African American to play in Major League Baseball. The world is shocked when the mutilated body of aspiring actress Elizabeth “Black Dahlia” Short is discovered in Los Angeles, the victim of a still-unsolved murder. And a series of events fuel decades of UFO conspiracies: an unidentified spacecraft crashes in Roswell, New Mexico; Seaman Harold Dahl meets the mysterious “Men in Black” in Puget Sound; and Kenneth Arnold makes the first widely reported UFO sighting near Mount Rainier, Washington. The comics’ world loses the creator of Wonder Woman, William Moulton Marston, who dies at age 53. And while comic fans thrill to the adventures of Captain America in the pages of Timely Comics, his creators are planning something very different for their next big project: Young Romance.

Like many other things in the golden age of comics, romance comics find their roots in other popular fiction and literature. Romance novels were released as early as 1740 with Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (also titled Virtue Rewarded). Of course, Jane Austin popularized the genre with the success of books like Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Emma. These classical literary roots gave rise to more mainstream books as the pulp market gained popularity in the early twentieth century. In fact, romance magazines were one of the top three most popular genres of the pulps (along with westerns and detective stories). When you factor in all the romantic stories that also appeared in the “more respectable” weekly magazines like The Saturday Evening Post, McCalls, and Redbook, it becomes clear that love permeated the popular culture consciousness of the time.

Like many other things in the golden age of comics, romance comics find their roots in other popular fiction and literature. Romance novels were released as early as 1740 with Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (also titled Virtue Rewarded). Of course, Jane Austin popularized the genre with the success of books like Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Emma. These classical literary roots gave rise to more mainstream books as the pulp market gained popularity in the early twentieth century. In fact, romance magazines were one of the top three most popular genres of the pulps (along with westerns and detective stories). When you factor in all the romantic stories that also appeared in the “more respectable” weekly magazines like The Saturday Evening Post, McCalls, and Redbook, it becomes clear that love permeated the popular culture consciousness of the time.

Richard Howell, explains, in his Introduction to Real Love: The Best of the Simon and Kirby Romance Comics 1940s-1950s:

Richard Howell, explains, in his Introduction to Real Love: The Best of the Simon and Kirby Romance Comics 1940s-1950s:

Romance has always been a major component in entertainment, be it novels, plays, or movies, but for over ten years after the first appearance of comic books, romance only had a token presence in their four-color pages.

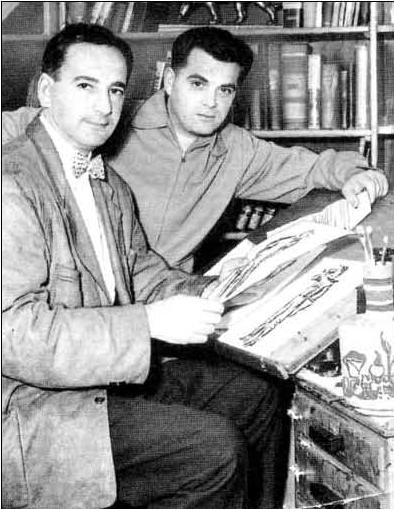

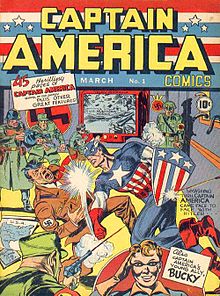

But things would change when Jacob Kurtzberg and Joe Simon returned home from World War II. Kurtzberg had previously worked in comics under a variety of pen names, including Jack Curtiss, Curt Davis, Lance Kirby, Ted Grey, Charles Nicholas, Fred Sande, and Teddy, before ultimately settling on the name Jack Kirby. Before the war, Kirby had collaborated with Joe Simon to create memorable superheroes for both Timely (Marvel) and DC comics; most notably, the star-spangled avenger known as Captain America, who debuted in 1940. But as superhero comics lost popularity after the end of World War II, Simon and Kirby were forced to explore and produce comics in other genres such as humor, horror, and crime comics.

In 1947, comic fans (and creators) were getting bored with these other genres and Simon and Kirby were looking for something new. As Mark Evanier writes in Kirby, King of Comics:

In 1947, comic fans (and creators) were getting bored with these other genres and Simon and Kirby were looking for something new. As Mark Evanier writes in Kirby, King of Comics:

There were odd jobs for several publishers, but nothing long lasting. Not until [Simon and Kirby] invented a new genre: the romance comic.

It came in two steps. First, there was “My Date,” which a sort of a romance comic, but skewed in a humorous Archie-like direction. That Title was for Hillman.

Jack Kirby summed it up as followed when he was interviewed for Will Eisner’s Shop Talk:

Kirby: I remember Joe and I were the first ones to create the romance comic magazine.

Eisner: That’s right. You and Joe Simon worked on a romance line.

Kirby: Joe and I were working for McFadden Publications at the time. McFadden had comics and in one of the books we did a feature called My Date. It suddenly occurred to me that McFadden was the biggest purveyor of romance in the world and was making millions at it, and we were sitting on top of the same thing, except that there were no romance stories in comics. My Date was a prelude.

Eisner: It was the first … .at least as far as I remember, it was.

Kirby: The first romance comics came from that discussion … Ideas come from discussion, and there we were, sitting on one of the staples of storytelling. In those days, it was either romances, westerns, or crimes as the big sellers.

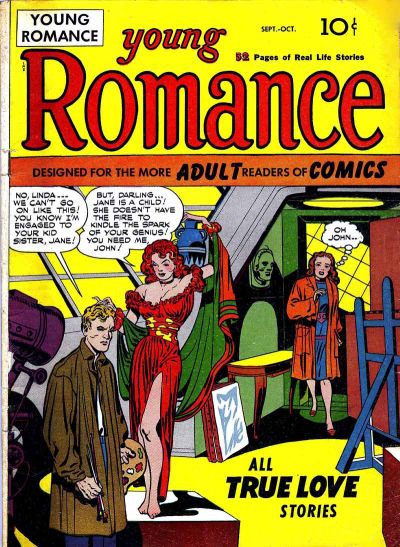

After the success of My Date, the next stage of romance comics came in the form of Young Romance, a more serious romance book, the cover of which boldly proclaimed itself to be, “designed for the more adult readers of comics.”

David Hajdu interviewed Simon for his book The Ten Cent Plague. Simon stated:

Comic books were supposed to be very juvenile, that’s what publishers thought . . . . It was supposedly very risky to put out love stories for children, but we knew that a lot of comic-book readers were high school age and, as a result, they wanted to read about people a few years older, so that’s how we approached Young Romance. We never talked down, and we were very realistic and adult. . . . The kids really liked what we were trying to do, I think because we didn’t treat them like kids. We were practically kids ourselves, so we didn’t look down on them.”

Simon expanded on this in an interview with Mark Evanier for the Jack Kirby Collector #25:

I had the Young Romance idea coming out of the service. I saw all these adults reading comic books and said, “Jeez, they’re all reading Disney and Donald Duck.” I got together a few pages of True Romance Confession and I thought the girls, the housewives that were reading comics, the housekeepers, the housemaids, everybody who was reading comics would really like to read some adult comics. I showed it to Jack and he loved it.

Although Young Romance was released by Prize comics, it should be noted that there was some resistance on the part of the publishers. Kirby tells, Evenier, “Mike [Bleiet] and Teddy [Epstein, the people who ran Prize] didn’t have much faith in Young Romance.” As a result, Simon and Kirby agreed to forgo upfront payment and were paid on the back end only if the book was a success. Of course, Simon was also able to negotiate for 50% of the profits from the book (and its follow up, Young Love). Simon explained to Evanier:

[T]he first thing we did, we agreed that we would do a whole issue; invest in a whole issue of Young Romance Comics before we peddled it to these gangsters that were publishing. (laughter) In this way, we would be protected. So we signed a contract; we were full partners in the thing. We were to pay for the art and editorial, they would pay for the publishing and do the publishing business. We thought we were pretty great with that contract–we were supposed to split the profits. We thought we were pretty damn smart to do that, but later I found out that these guys weren’t even putting their money into it. The distributors were giving them a 35% advance. So, they weren’t paying anything. We were the ones that were paying the money. The good part is that the thing sold out and that was really a bonanza. We were taking in tons of money.”

Simon and Kirby’s gamble paid off. Young Romance was a hit. In fact, the book sold almost a million copies, which would make it as successful as Captain America. As a result of the success of these books, it was estimated that each creator earned more than $1,000 per week from the books in 1950, which, when adjusted for inflation, is around $10,000 today.

Not everyone agrees that this was a step up for the legendary creative team. Harvey Kurztman wrote “The talents of Kirby and Simon were wasted on romance titles,” and explains in his book, From Aargh! to Zap! Harvey Kurztman’s Visual History of Comics:

Not everyone agrees that this was a step up for the legendary creative team. Harvey Kurztman wrote “The talents of Kirby and Simon were wasted on romance titles,” and explains in his book, From Aargh! to Zap! Harvey Kurztman’s Visual History of Comics:

The very first romance comic-book, Young Romance, in 1947, was the brainchild of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby—the same team that had brought so much vitality to the super-hero comic books a few years earlier. So far had the mighty fallen.

Similarly, it is interesting to note that very little is written about the work Simon and Kirby did in the romance comics genre. Authors Pierre Comtois and Gregorio Montejo suggest the reason for this in their article, An Exercise In Realism, Kirby’s Romance Comics, which appeared in Jack Kirby Collector 20:

The simple answer is that Kirby’s romance comics are not as accessible as his efforts in other, more action-oriented genres such as science-fiction, western or super-hero comics. The more complicated answer is that romance comics are too close to real life. After all, how realistic is it that a reader would encounter savage Indians, bug-eyed monsters or costumed supermen in their day to day lives? Uncluttered by such unrealistic distractions, romance comics are free to explore the more quiet drama of real life—the incidents, heartbreaks, and human conflicts that are actually encountered in the lives of their readers. Thus romance comics have had the perfect camouflage: Made up of the familiar details of daily life, they have not stood out. Instead, they have receded in the minds of readers as their more colorful competitors on the magazine racks have loomed ever larger in their more exaggerated presentations.

At the risk of stating the obvious, Young Romance was far from the first comic to feature female characters. As David Hajdu sums up:

Comic books had had heroines intended to appeal to young women and men alike since the war years, when the quotient of females in the home-front marketplace expanded at the same time that military readership increased the demand for drawings of shapely young female characters suitable for pinning up. With many male artists drafted, moreover, women artists found more work and were frequently assigned to do the female-oriented comics. There were jungle girls to outnumber the African population: Camilia (drawn by Fran Hopper and the supremely talented Marcia Snyder), Judy of the Jungle (by the versatile Alex Schomberg), Tiger Girl (by Matt Baker), Sheena (perpetuated by innumerable artists under Jerry Iger, and countless others.) There were costumed heroines and quasi-military heroines: Phantom Lady (by Matt Baker), Yankee Girl (by Ann Brewster), the Blond Bomber, and the Girl Commandos (both of the latter drawn by Jill Elgin and Barbara Hall). There were science-fiction heroines-Gale Allen and Her All-Girl Squadron and Mysta of the Moon (both by Fran Hopper) — and there was a wondrous assortment of strong, smart, and sexy proto-postfeminists: the nurse-turned-aviatrix Jane Martin (by Fran Hopper and Ann Brewster), “girl detective” Glory Forbes (by Jean Levander), and the crime-solving fashion model Toni Gayle (by Janice Valleau, who sometimes signed her married name, Winkleman). “We always had a love angle, even though the stories were adventure stories, really, but the girls in the stories, like Toni Gayle, who I loved to do, had it all over the men,” said Janice Valleau Winkleman. “Even in the love stories, where the girls were always chasing the men, the girls were smarter and sexier.”

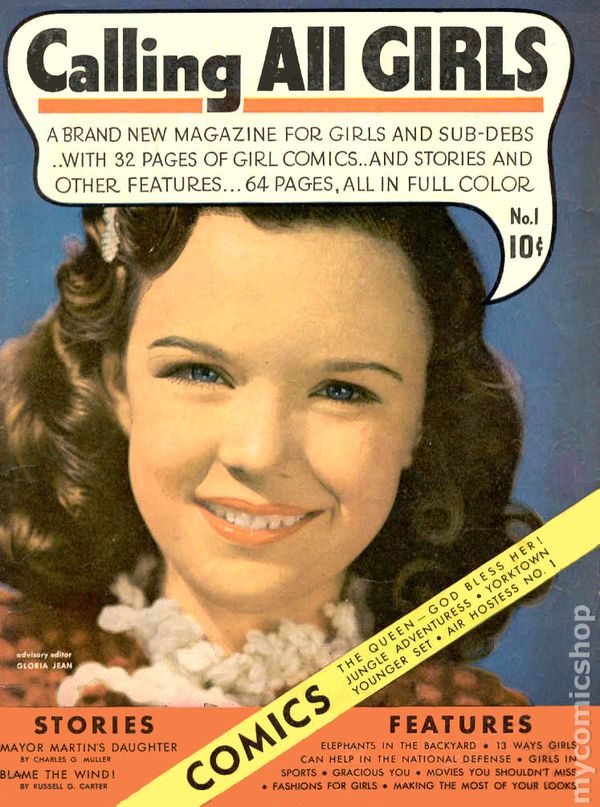

And while it is undisputed that Young Romance created the romance genre in comics, I think honorable mention should also be given to Calling All Girls published by Parent’s Magazine, which debuted in July, 1941. Primarily filled with comics, Calling All Girls was the first comic to be marketed to girls. Calling All Girls also contained short stories and advice on fashion and manners. Calling All Girls contained some of the earliest romance stories (mostly in text form) and bridged the gap between pulps and comics. As a result of paper shortages, Calling All Girls stopped including comics in January 1946, the year before Young Romance was released. Interestingly, neither Parents Magazine nor Calling All Girls would get back into the romance comics business even at the height of the popularity of the genre in 1950.

And while it is undisputed that Young Romance created the romance genre in comics, I think honorable mention should also be given to Calling All Girls published by Parent’s Magazine, which debuted in July, 1941. Primarily filled with comics, Calling All Girls was the first comic to be marketed to girls. Calling All Girls also contained short stories and advice on fashion and manners. Calling All Girls contained some of the earliest romance stories (mostly in text form) and bridged the gap between pulps and comics. As a result of paper shortages, Calling All Girls stopped including comics in January 1946, the year before Young Romance was released. Interestingly, neither Parents Magazine nor Calling All Girls would get back into the romance comics business even at the height of the popularity of the genre in 1950.

So, what exactly was Young Romance? Perhaps the best way to sum it up is to examine the five stories that appeared the first issue.

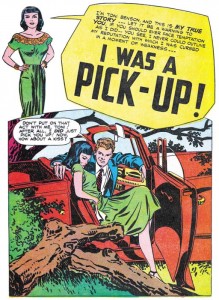

The first story is the longest and most mature of the issue. “I Was a Pick-Up” tells the story of Toni, a sheltered 17-year-old who makes a dress and goes on the town. During her adventures, Toni takes a ride from a convertible-driving rich boy named Bob, who later abandons her at roadhouse when the place is raided. Luckily, bad boy Stanley rescues her. Sadly, Stanley leaves Toni with a note that says she is better off without him. However, two pages later, Toni has barely escaped another yet another lout, when she meets a reformed and now-successful Stanley in a gas station. They live happily ever after.

The first story is the longest and most mature of the issue. “I Was a Pick-Up” tells the story of Toni, a sheltered 17-year-old who makes a dress and goes on the town. During her adventures, Toni takes a ride from a convertible-driving rich boy named Bob, who later abandons her at roadhouse when the place is raided. Luckily, bad boy Stanley rescues her. Sadly, Stanley leaves Toni with a note that says she is better off without him. However, two pages later, Toni has barely escaped another yet another lout, when she meets a reformed and now-successful Stanley in a gas station. They live happily ever after.

The second story, “The Farmer’s Wife” shows how a 21-year-old wife must adapt to living with her 36-year-old husband. The third story, “Misguided Heart” introduces us to June, a factory worker who chooses as her true love her co-worker over the self-entitled son of the factory owner. The fourth story (not drawn by Simon or Kirby), “The Plight of the Suspicious Bride Groom,” focuses on a bellhop who breaks up engagements for fun and the bride groom that stops him. Finally, the fifth story is a typical boy from the wrong side of the tracks tale entitled “Summer Song.”

Because it was the first book of its kind, there was obviously nothing like it on the market. Young Romance had no competition. But that would quickly change. Simon tells Hajdu:

Nobody else knew how good we were doing for a couple of years, and then everyone started copying us.

The first real competition would come from Simon and Kirby’s former bosses at Timely (Marvel). Les Daniels in Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World’s Greatest Comics, writes:

“Love” comics had suddenly become popular and so Marvel introduced My Romance in September 1948. Close behind it were Love Romances, Love Adventures, Love Tales, Love Dramas and a load of others, including My Love and Our Love. Again, Marvel was playing follow the leader, and again, some of the titles in this new genre would enjoy unusually long runs. The redundantly titled Love Romances, kept on chronicling the trials of the heartbroken until July, 1963.

Daniels also writes in DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World’s Favorite Comic Book Heroes:

Daniels also writes in DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World’s Favorite Comic Book Heroes:

The romance comics craze caught on slowly at DC . . . . When DC finally attempted a full-fledged love title, editor in chief Irwin Donnenfeld made the unprecedented decision to hire a woman as editor. “The romance magazines really appealed to young girls,” he says, “so I felt a woman would have a better handle on what a young girl would like, better than a guy like Bon Kanigher, who was doing war books.”

DC first hired Zena Brody to launch Girls’ Love Stories. Brody was followed by several other women editors, including Ruth Brandt, Phyllis Reed, and Dorothy Woolfolk, who worked on Secret Hearts, Girls’ Romances, Falling in Love, Heart Throbs and even Young Romance, which DC purchased in 1963. Daniels points out that, “[These women] helped open doors for the many women who occupy important positions today, long after love comics have become only a memory.”

DC and Marvel were not alone in their amorous pursuits and several sources report there were as many as 148 romance comics titles from at least 26 publishers. Love stories made up more than one-fifth of the market. These love stories all followed a basic theme. Doug Harvey writes in My Affair With Romance Comics, LA Weekly News:

A typical romance story was told in the first person, allegedly from a true account confided to a trusted comic book professional. They generally followed a predictable dramatic arc, with a fairly wide range of crises — unrequited love, class barriers, jealousy, career conflicts, haunted pasts, etc. — inevitably resolved with a monogamous happily-ever-after ending. “Well, darling, suddenly I don’t love you anymore! I can’t explain it — but I just don’t!” announces Tony at the outset of “Changes of Heart,” the lead story from the April 1965 issue of Young Romance (the longest-running title in the romance pantheon). He and Brenda had been so right for each other. Then — boom! The thrill is gone! Brenda doesn’t know how she’ll carry on. She dates, but can’t get Tony out of her head. One night the doorbell rings — “It’s Tony!” she thinks. But it isn’t Tony, it’s Tony’s old friend Bill Oliver. Tony’s blown town with no forwarding address, and Bill thought she might know where to find him. Brenda breaks down sobbing, spilling the whole story. Bill listens sympathetically, then admits that he, too, was recently dumped. They start hanging out, and suddenly realize they’ve fallen for each other. “There was no need for words — our love was strong because it had been born out of pain.”

In the comic’s industry in the ’40s, crime was king. In 1950, romance became the queen. Michelle Nolan summarizes in the very thorough book on the history of Romance Comics entitled Love on the Racks:

Never before and never again, did a single genre of the comic book — an original American commercial concept — explode in such an orgy of financial opportunism. . . . Some historians have theorized that the demise of the pulp magazines had something to do with the frenzy for love . . . . No, the answer — if there is a rational answer — is that it was just time for love. Teenage American girls — for it was they that read the majority of romance comics — were ready for romance. No young miss could possibly avoid spotting love on the racks when it was that freely available. And more love begat even more love.

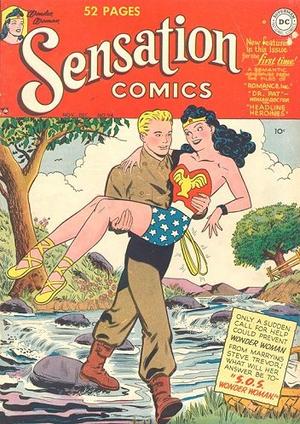

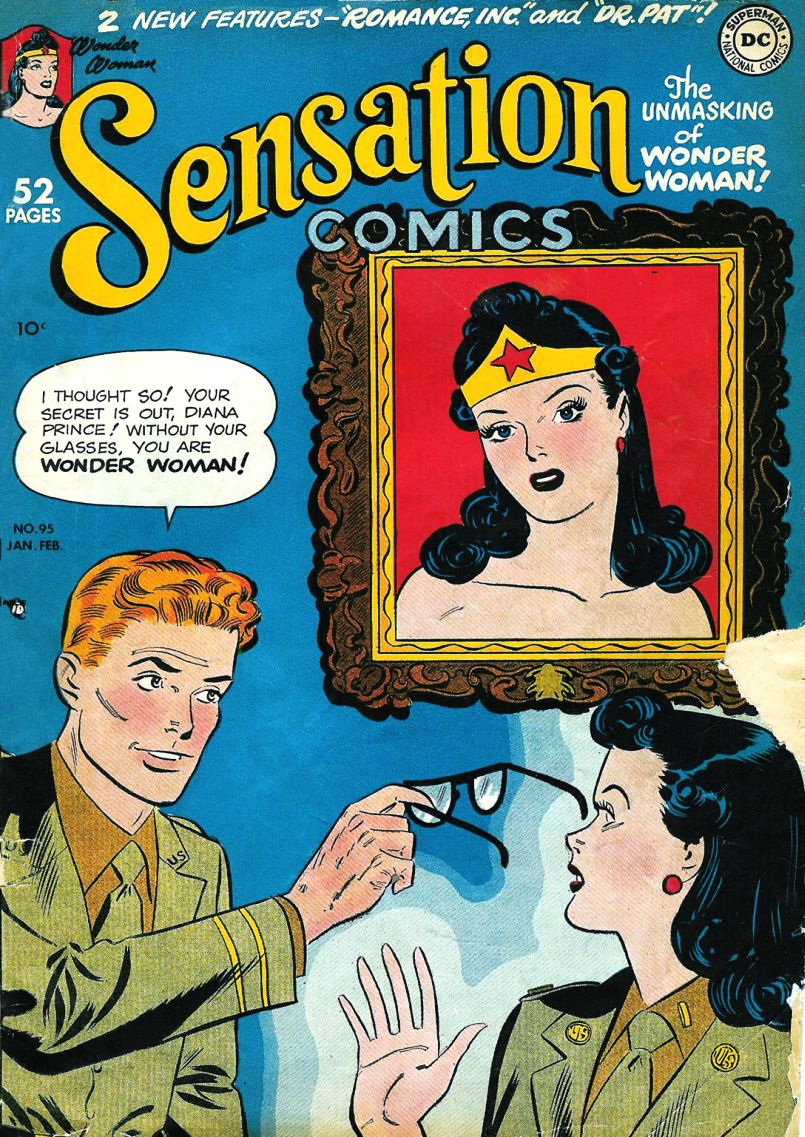

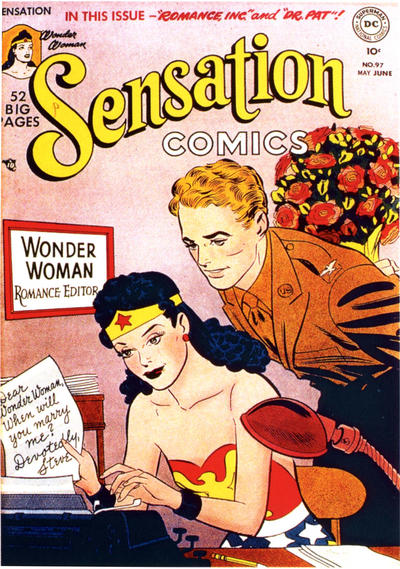

Even feminist icon Wonder Woman was getting into the act by changing her covers to conform with this new love mania with drastic changes to the covers of Sensational Comics, beginning after issue 93.

As long as I’ve digressed to the topic of cover, I should also mention that photo covers also began to gain popularity as a result of the popularity of the Romance Comics.

Love comics were not only good for the wallets of comic companies. They also helped alleviate some of the growing public concern against comics. The January 31, 1949, edition of The New York Times pronounced that the anti-comics drive was waning and that romance comics (called “love” type comics in the article) were replacing crime comics on the newsstands.

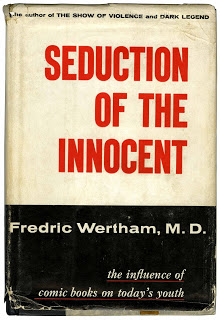

Of course, as expected, some critics could not be swayed. Dr. Hilde Mosse told the Emerson School that romance comics presented a “distorted picture of love.” However, it was Dr. Mosse’s colleague and co-founder of the Lafargue Clinic in Harlem, Fredric Wertham, who posed the greatest threat against all genres of comics, including romance comics. As Amy Kiste Nyberg writes in Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code:

The issue of gender is linked to violence in Wertham’s study, since women are generally victims in comic books. Wertham believed the blending of sensuality with cruelty was a particularly disturbing aspect of comic book ideology that had a great deal of resonance with the disdain for the opposite sex that young male readers often had. In many comic books, women were portrayed as objects to be abused or to be used as decoys in crime settings. Women who did not fall into the role of victim were generally cast as villains, often with masculine or witchlike powers. These plots suggested that men had to present a united front against such women. Wertham commented, “In these stories there are practically no decent, attractive, successful women” (191). Wertham also objected to the genre known as romance or love comics. Such comics moved from the realm of physical violence against women to psychological violence in which the main female character is often humiliated or shown to be inadequate in some way.

In fact, there are several sections in Wertham’s book, Seduction of the Innocent, that deal with romance comics.

First, Wertham puts his own spin on the Simon and Kirby’s creation of the romance comics genre:

The experts had said that what the children need is aggression, not affection — crime, not love. But suddenly the industry converted from blood to kisses. They tooled up the industry for a kind of comic book that hardly existed before, the love-confession type. They began to turn them out quickly and plentifully before their own experts had time to retool for the new production line and write scientific papers proving that what children really needed and wanted — what their psychological development really called for — was after all not murder, but love!

Wertham next compares romance comics to their crime counterparts (and similarly finds them lacking).

In many of them, in complete contrast to the previous teen-age group, sexual relations are assumed to have taken place in the background. Just as the crime-comics formula requires a violent ending, so the love-comics formula demands that the story end with reconciliation.

* * *

Studying these love-confession books is even more tedious than studying the usual crime comic books. You have to wade through all the mushiness, the false sentiments, the social hypocrisy, the titillation, the cheapness.

* * *

Flooding the market with love-confession comics was so successful in diverting attention from crime comic books that it has been entirely overlooked that many of them really are crime comic books, with a seasoning of love added. Unless the love comics are sprinkled with some crime they do not sell. Apparently love does not pay.

* * *

Love comics do harm in the sphere of taste, esthetics, ethics and human relations. The plots are stereotyped, banal, cheap. Whereas in crime comics the situation is boy meets girl, boy beats girl; in love comics it is boy meets girl, boy cheats girl — or vice versa. (p. 185)

Wertham also challenged the intended audience for the books:

It is a mistake to think that love comics are read only by adolescent and older children. They are read by very young children as well. An eight-year-old girl living in a very comfortable environment on Long Island said, “I have lots of friends and we buy about one comic book a week and then we exchange. I can read about ten a day. I like to read the comic books about love because when I go to sleep at night I love to dream about love.”

Finally, Wertham took issue with the portrayals of race and gender in the books:

False stereotypes of race prejudice exist also in the “love comics.” Children can usually pick the unsatisfactory lover just by his looks.

I should add that Wertham did not discuss romance comics when he testified in front of the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency. And while numerous romance comics were reviewed by the Committee, the genre is not specifically discussed in the findings of the Senate.

Were Wertham’s criticisms wrong? As Bradford W. Wright writes in Comic Book Nation, romance comics were not very empowering:

[In Teen Age Brides] The secret to achieving a happy marriage . . . is for the wife to give “unselfishly and unfailingly.” Of course, when in another story the situation is reversed [it is] again the wife who is being selfish . . . . [The Husband’s] happiness comes first and she is all the happier for accommodating his wishes.

Self-denial for the sake of marriage was especially important where the woman’s career was concerned. Romance comic books discouraged women from entering the work force. Working women in the comic books remained unfulfilled and unhappy because their careers complicated relationships and jeopardized their prospects for marriage. . . . Another reason for women to stay out of the workplace, according to romance comic books, was that men were not attracted to ambitious women. . . . . Men, on the other hand, needed and deserved their independence.

Of course, there was also Romantic Hearts #9, which pretty much epitomizes everything Wertham warned against.

The comics industry took into account many of the criticisms leveled against romance comics when it enacted the Comics Code Authority in 1954. The Comics Code was implemented to help stave off the backlash against comics and is credited with destroying much of the comic industry and curtailing free speech and creativity for decades. Several specific provisions were directly leveled at romance comics and the advertisements found in them.

Some the general code provisions in the Code for Editorial Matter ensured that there could be no more bad boy stories or rebellious teens or wrong side of the tracks stories. This is because General Standards Part A, provided that:

3. Policemen, judges, government officials, and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.

4. If crime is depicted it shall be as a sordid and unpleasant activity.

5. Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates the desire for emulation.

6. In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

In addition, the Code ensured that sordid or lust filled stories would no longer appear on the stands, General Standards Part B, provided:

2. All scenes of horror, excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust, sadism, masochism shall not be permitted.

3. All lurid, unsavory, gruesome illustrations shall be eliminated.

General Standards Part C got rid of the colorful double entendre dialogue:

1. Profanity, obscenity, smut, vulgarity, or words or symbols which have acquired undesirable meanings are forbidden.

Other provisions directly affected the look of and marketability of the books, such as General Standards Part C as it related to Costume:

1. Nudity in any form is prohibited, as is indecent or undue exposure.

2. Suggestive and salacious illustration or suggestive posture is unacceptable.

3. All characters shall be depicted in dress reasonably acceptable to society.

4. Females shall be drawn realistically without exaggeration of any physical qualities. NOTE: It should be recognized that all prohibitions dealing with costume, dialogue, or artwork apply as specifically to the cover of a comic magazine as they do to the contents.

The final, and most important nail, in the romance comics coffin related to General Standards Part C related to the treatment Marriage and Sex

1. Divorce shall not be treated humorously nor represented as desirable.

2. Illicit sex relations are neither to be hinted at or portrayed. Violent love scenes as well as sexual abnormalities are unacceptable.

3. Respect for parents, the moral code, and for honorable behavior shall be fostered. A sympathetic understanding of the problems of love is not a license for moral distortion.

4. The treatment of love-romance stories shall emphasize the value of the home and the sanctity of marriage.

5. Passion or romantic interest shall never be treated in such a way as to stimulate the lower and baser emotions.

6. Seduction and rape shall never be shown or suggested. 7. Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden.

To close the loop, I also wanted to provide the provisions related to the Code for Advertising Matter, which appeared aimed at a lot of the romance book ads. Such as:

1. Liquor and tobacco advertising is not acceptable.

2. Advertising of sex or sex instruction books are unacceptable.

3. The sale of picture postcards, “pin-ups,” “art studies,” or any other reproduction of nude or semi-nude figures is prohibited.

7. Nudity with meretricious purpose and salacious postures shall not be permitted in the advertising of any product; clothed figures shall never be presented in such a way as to be offensive or contrary to good taste or morals.

9. Advertisement of medical, health, or toiletry products of questionable nature are to be rejected. Advertisements for medical, health or toiletry products endorsed by the American Medical Association, or the American Dental Association, shall be deemed acceptable if they conform with all other conditions of the Advertising Code.

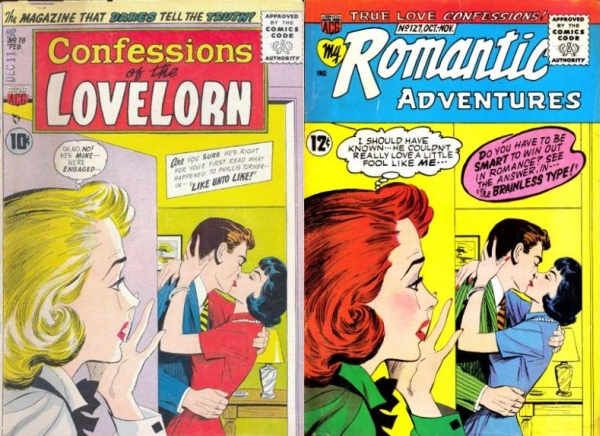

Perhaps the best way to explain how the Code affected romance comics in the market is by showing examples of how the Code changed pre-Code books that were issued as reprints after the Code was enacted. Comic Book Resources did an excellent study on the covers of some of these books in its article “Scott’s Classic Comics Corner: ACG’s Recycled Romance.” Below, I have included some of the images from that article. To see them all go to http://goodcomics.comicbookresources.com/2009/10/06/scotts-classic-comics-corner-acgs-recycled-romance/

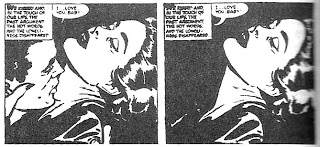

Here is another example I found in Comics Buyer’s Guide. The panel on left appeared in Harvey Comics’ Teen-Age Bride #5 (published before the Code), the panel on the right is from the reprint in Teen Bride-to-Be Romances #20 (published post-Code).

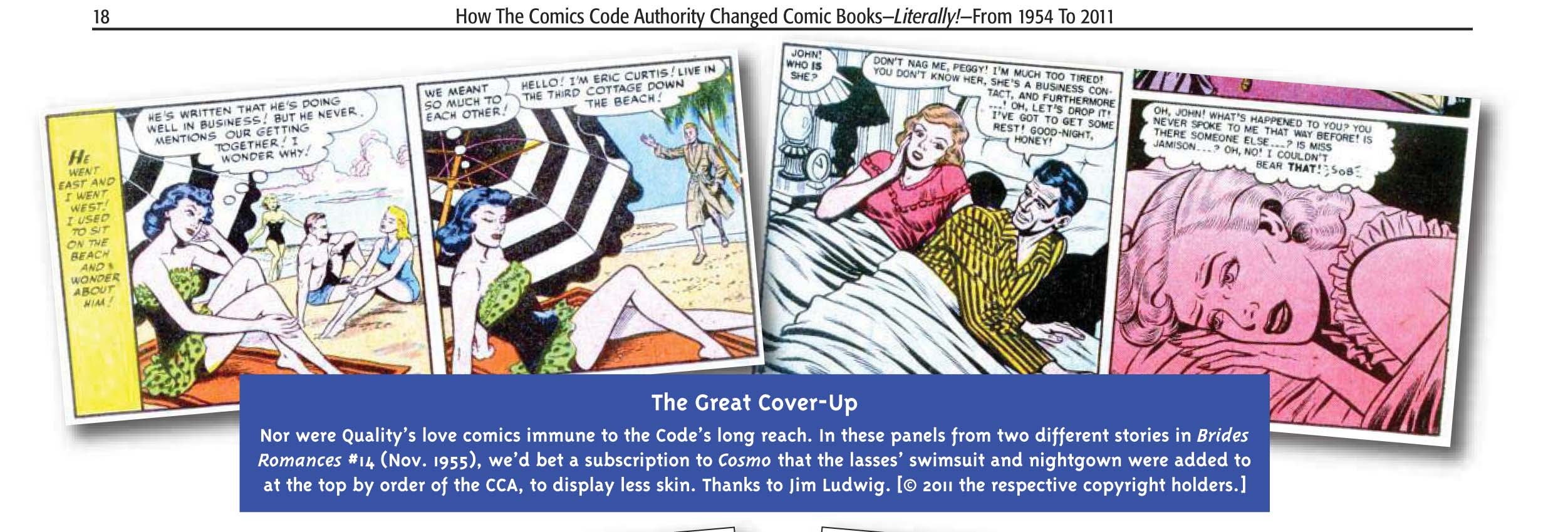

The effect of the Code could be best summarized by Richard J. Arndt in “How The Comics Code Authority Changed Comic Books—Literally!—From 1954 To 2011” in Alter Ego 105:

The romance genre was gutted. Nothing that resembled anything a real teenager might experience was allowed anymore. Even though the lovers in the stories looked like full-grown adults, most of these characters seemed to have no clue whatsoever on how to deal with an actual relationship. No comics that tried to show real problems and possible solutions to them were allowed under the Code, and although the genre stumbled along until the mid-1970s, it eventually withered and died.

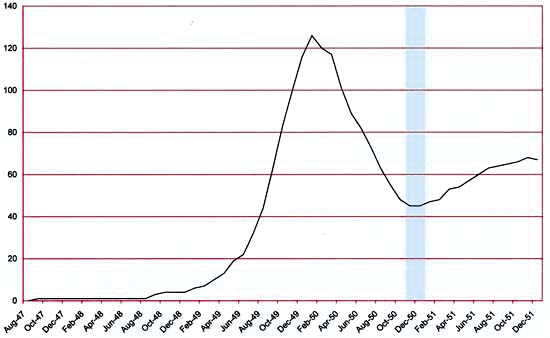

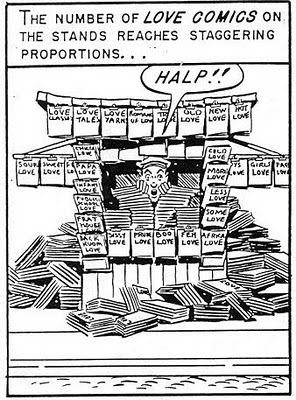

Interestingly, while many people charge the Comics Code with the destruction of the romance comics genre, the truth of the matter is that sales had begun decreasing long before the Code was implemented. Romance comics may have been queen, but her reign was limited. By the beginning of 1951, the number of romance comics titles had decreased by over 60%. According to the Kirby Museum, by 1951 there were only 45 romance comics on the racks. Of course, this was still a respectable number, but far fewer from the high of 148 in 1950. Quite simply, the market was oversaturated.

Nolan explains in Love on the Rocks:

The aftermath of the Love Glut was like nothing that had ever occurred in American comic book publishing. Unlike the demise of horror and crime titles in the mid-1950s, the near simultaneous disappearance or suspension of more than 100 romance titles in 1950 did not involve censorship or the excessive outcries of outraged parents, teachers and librarians. It was simply a classic example of too much supply and too little demand, not to mention too little space on the racks.

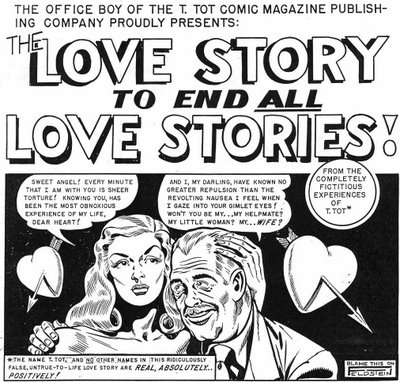

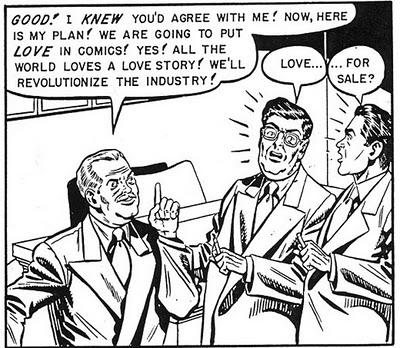

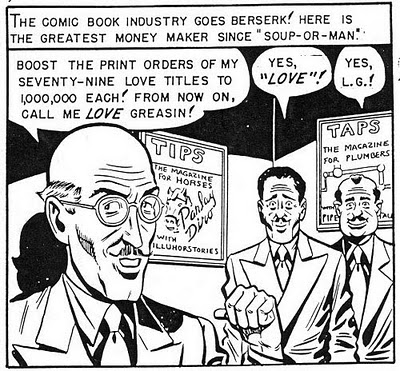

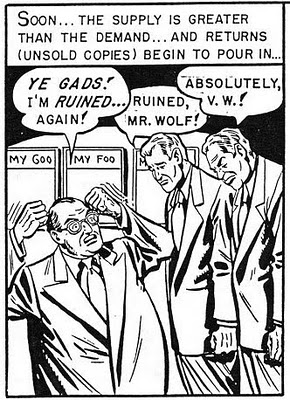

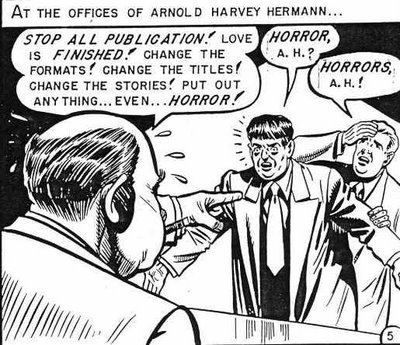

Al Feldstein and Bill Gaines perfectly parodied this phenomenon in EC’s Modern Love in “The Love Story to End All Love Stories.” But rather than describe their brilliance, I thought I would provide some highlights.

As Eddie Campbell explains in It’s just comics — Part 14 (available at http://eddiecampbell.blogspot.com):

When market congestion caused the roof to fall in, Marvel cut its 31 romance titles down to 7. Quality cancelled all 14 of its titles and brought back three of them six months later in 1951. The other companies either scaled down the romance thing or got out of it. There were even a couple who had published moderately before the glut and continued moderately after it. But what about Fox? Fox got rid of all 21 of its love books, mostly by converting them into other genres: My Love Affair became March of Crime at #7 after only six issues; My past continued as Crimes Inc after #11; Women in Love became Feature Presentation after four issues; My Experience changed again, this time to Judy Canova after #22; My Love story became Hoot Gibson; My Great Love became Will Rogers Western; My Secret Affair became Martin Kane , Private Eye from #4; My Secret Romance became Star Presentation from #3; My intimate Affair changed to Inside Crime; My Private Life became Pedro Fox at #18 after previously being

John Lustig, discussed the effect of the Code with Nolan for “Death of Romance (Comics!!),” which appeared in Back Issue 13. He writes:

While the Comics Code devastated the horror and crime genres in the mid-’50s, romance seemed relatively unscathed—at first. In fact, Nolan thinks the Code initially strengthened the romance genre— at least in terms of market share “for a little while.”

Compared to other genres, says Nolan, romance comics were only “censored a little bit.”

Still, with the Code restrictions in place, romance comics could not compete with the other mediums were aggressively vying for consumer dollars without censorship. First, there was the growing underground comix market, which featured unrestricted and uncensored writing and often contained graphic sex and nudity. Second, Harlequin Books began producing more and more novels, which enticed readers with their painted covers and flowery prose. Finally, romance comics simply couldn’t compete with the growing popularity and presence of television, specifically the soap opera, which featured many of the themes present in romance comics and provided free daily gratification. This is especially true when you factor in that comics were moving to the direct market, which focus on superhero comics.

As Lustig points out, at the same time, the superhero comics (especially at Marvel) were becoming more like soap operas.

With Marvel superheroes, fans got a lot of the same emotional content as traditional romance comics — plus capes, tights, and slugfests!

“Instead of looking at each other longingly across a typing pool, the protagonists did the same while trying to save the world,” notes [Lance] Tooks.

Ironically, the astounding sales of Marvel’s romance-soaked super-hero books helped hasten the demise of traditional romance comics (and other genres.) “The success of the Marvel super-heroes made DC change their priorities and chase Marvel super-heroes,” comments [Dick] Giordano. “Remember that Westerns, mysteries, and crime titles all disappeared to make room for the Spandex crowd.”

Marvel and DC were out of the love business in the 1970s; Charlton stayed in the game the longest, until June 1983, with Soap Opera Love #3. After that, romance comics were no more (although some may argue that Strangers in Paradise still fits in the genre). Dick Giordano, who worked for both Charlton and DC artist, offers some final thoughts:

[G]irls simply outgrew romance comics … [The content was] too tame for the more sophisticated, sexually liberated, women’s libbers [who] were able to see nudity, strong sexual content, and life the way it really was in other media. Hand holding and pining after the cute boy on the football team just didn’t do it anymore, and the Comics Code wouldn’t pass anything that truly resembled real-life relationships.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net