When an artist is censored by a government agency or political group, the immediate focus is on the individual case: Who is being censored, who is doing the censoring, and what are the reasons for the censorship? An unseen consequence of any act of censorship, however, is the resulting acts of self-censorship by other artists, who impose restrictions on their own work out of fear of government or political sanctions. A new book by Russian artist Victoria Lomasko chronicles the increasing acts of self-censorship in Russia as that nation’s Orthodox church takes a greater role in attacking art it deems religiously offensive.

When an artist is censored by a government agency or political group, the immediate focus is on the individual case: Who is being censored, who is doing the censoring, and what are the reasons for the censorship? An unseen consequence of any act of censorship, however, is the resulting acts of self-censorship by other artists, who impose restrictions on their own work out of fear of government or political sanctions. A new book by Russian artist Victoria Lomasko chronicles the increasing acts of self-censorship in Russia as that nation’s Orthodox church takes a greater role in attacking art it deems religiously offensive.

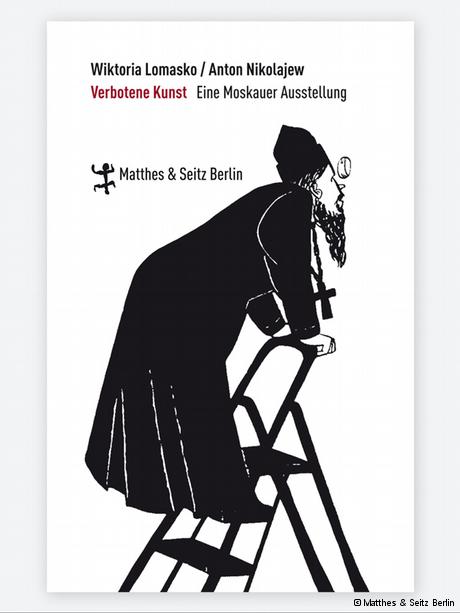

In Verbotene Kunst. Eine Moskauer Ausstellung (Forbidden Art. A Moscow Exhibition), Lomasko and Russian journalist Anton Nikolayev document the state trial against museum curators Andrei Yerofeyev and Yuri Samodurov. The curators held an exhibit displaying artistic works that “had been removed from Russian museums and galleries on political and religious grounds. An organization of Orthodox believers pressed charges against the exhibition for inciting religious hatred.”

In an interview with Germany’s Deutsche Welle, Lomasko explains why she drew cartoons about the trial:

“I got an incredible push as an artist,” she explains. “For the first time, I came in close context with Orthodox activists. Originally, I didn’t at all want to attend the entire trial and ultimately publish a book. And I never would have pulled it off if it weren’t for those activists. They inspired me. I even came to like them because they delivered so many wonderful and unbelievable scenes. I just sketched everything that I saw and wrote down everything I heard. It was incredible what they were saying! It was like being in the Middle Ages.”

Lomasko explains that the trial against Yerofeyev and Samodurov did not cause a huge ripple in the Russian art scene because many artists “thought the two didn’t really have anything to fear — maybe a fine in the worst case. But in the end it became clear that they might go to jail. As far as I know, they were spared prison time only because important people with political connections got involved.” It wasn’t until the following trial against the musical group Pussy Riot that artists understood the dangerous new waters they were navigating. According to Lomasko, what the Pussy Riot trial made clear was how “nobody made any secrets about the fact that the state is completely on the church’s side, that the verdict had been decided in advance, that the true judges are called President Putin and Patriarch Kirill, and that a similar fate awaits anyone who dares to contradict the two of them.”

In the wake of jail time for the group, Lomasko argues that what followed was an escalation of artistic attacks and government censorship. “All artists,” she explains, “were made to understand, ‘If you all dare to go too far, then we’re going to take you on.’ But that only encouraged artists to do more and to criticize further the increasing strength of the church, which is no longer separated from the state. In return, of course, the government is going to sharpen laws even more.”

Lomasko does not see a truce coming between the Orthodox church and Russian art scene, and ultimately she worries that this is not a battle Russian artists can expect to see ending with any sense of real artistic freedom:

“No. Even if we, as artists, didn’t do anything or show works openly critical of the church and religion, people will attack our exhibitions and our world. The other side is the increasing self-censorship. Many gallery owners, curators and museum representatives don’t even want to create an opportunity for those Orthodox censors to appear at their doorstep. They themselves no longer want to show certain works. Some people are using the situation to get press. Others are afraid of scandals and take cover in self-censorship. And even others want to become heroes by holding tight to the issue.”

Lomasko uses herself as an example of an artist caught in post-Pussy Riot Russia when she insists that “I definitely don’t want to become a media figure. And I also don’t think of myself as being forced to resort to self-censorship or turning myself into a heroine.” Lomasko’s position highlights the dangers of artistic expression in Russia at the moment. If artists do not want to become a media figure, they are increasingly wary of the art they create, and the risk for all of us is that too many artists may choose to self-censor their work and only produce art that meets the approval of society and the government instead of art that is true and unrestrained creative expression.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Mark Bousquet is the Assistant Director of Core Writing at the University of Nevada, Reno, and reviews movies and television programs at Atomic Anxiety.