A recent profile of political cartoonist Khalid Albaih in The New York Times highlights the changing nature of rebellion and protest in the 21st century. Placing Albaih at the center of several different dynamics — between depiction and inspiration and between traditional and social media forms of protest — the Times‘ piece illustrates the importance of political cartoons in the Arab world. Albaih’s work depicts the problems he sees in the region, and his cartoons then inspire future rounds of protest, which often takes the traditionally rebellious form of graffiti and spreads through social media services like Facebook.

A recent profile of political cartoonist Khalid Albaih in The New York Times highlights the changing nature of rebellion and protest in the 21st century. Placing Albaih at the center of several different dynamics — between depiction and inspiration and between traditional and social media forms of protest — the Times‘ piece illustrates the importance of political cartoons in the Arab world. Albaih’s work depicts the problems he sees in the region, and his cartoons then inspire future rounds of protest, which often takes the traditionally rebellious form of graffiti and spreads through social media services like Facebook.

Being a political cartoonist in the Arab world in the wake of the Arab Spring protest movement is a potentially dangerous pursuit, but Albaih was raised in a household that confronted political and social issues on a daily basis. Albaih’s father was a Sudanese diplomat stationed in Romania (where Albaih was born), and his mother campaigned against the Sudanese practice of female genital mutation.

The young Albaih found inspiration in comics. His artwork mixes old school and new school techniques, “part traditional ink on paper and part computer design.” Albaih’s inspirations included the Egyptian cartoonist Sabah al-Kheir and the Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali, “who was renowned for his criticism of Arab governments and the Israeli occupation of Arab lands.”

While some critics of the Arab Spring have pointed to the unrest in the region as a negative, Albaih cites the French Revolution as an inspiration for people to not give up: “I hate it when people say it failed; it took the French Revolution 70 years to settle!”

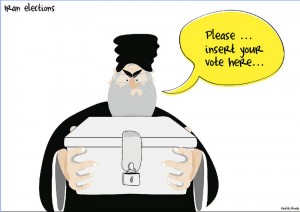

His career as a political cartoonist was slow to take off as traditional publishers did not find his drawings worthy of publication. In response, Albaih turned to social media, starting his own Facebook page to display his art and voice his social criticisms. Albaih frequently targets people in power:

Mr. Albaih’s “The Rest Will Follow” was one foretelling cartoon. It featured a fist with different Arab flags painted on each finger. The Tunisian flag was affixed to the raised middle finger, a message Mr. Albaih meant for Arab dictators.

Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution succeeded; soon revolutionaries poured into the streets in Egypt. But when Hosni Mubarak, the longtime Egyptian leader, showed no signs of ceding power, Mr. Albaih posted a silhouette of Mr. Mubarak’s face with the word “Egypt” in Arabic next to it. It was marked with an accent, though, that altered the word’s meaning to “insistent.”

As his reputation grew thanks to social media, Albaih’s artwork began to inspire people to further their protests, and despite its digital beginnings, Albaih’s artwork was transformed by protesters to the street. An Egyptian protester sent an email to Albaih, “telling him that his political cartoon had become a symbol for the Egyptian protesters, spray painted on the streets as antigovernment graffiti.” Albaih’s artwork was thus spread through social media and recreated on the very streets that inspired his work.

Albaih is aware that his art makes him susceptible to targeting by the regimes he criticizes. While insisting, “I don’t think I’m famous,” Albaih’s artwork was used for this year’s Reporters Without Borders’ annual postcard and he has no desire to slow his production rate or alter his subject. “I am careful,” he insists, “but if something happens, it happens.”

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Mark Bousquet is the Assistant Director of Core Writing at the University of Nevada, Reno, and reviews movies and television programs at Atomic Anxiety.