A recent exhaustive survey of challenges and bans of materials in Massachusetts public libraries has uncovered a few cases involving comics and graphic novels — as well as a major shortcoming in the state’s public records law, which allows libraries to dispose of complaint records as soon as a challenge is resolved.

A recent exhaustive survey of challenges and bans of materials in Massachusetts public libraries has uncovered a few cases involving comics and graphic novels — as well as a major shortcoming in the state’s public records law, which allows libraries to dispose of complaint records as soon as a challenge is resolved.

The survey was conducted by Chris Peterson, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Civic Media and a board member of the National Coalition Against Censorship. After a previous Mapping Banned Books project using national data from the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, Peterson wanted to try to build a complete picture of book challenges and bans in his home state to see how it compared. The data compiled by OIF, while a valuable resource for librarians and other researchers, is admittedly incomplete because it relies on media reports and self-reporting from libraries. Peterson suspected there may have been many more cases that never made the news and were not reported to OIF, so he took advantage of the Freedom of Information Act and the state’s public records law to ask every publicly-funded school, municipal/regional, and prison library in Massachusetts for any documents they had pertaining to challenges or bans of materials in their collections.

Using tools from MuckRock, a Boston-based organization that facilitates FOIA requests and makes the results available on its website, Peterson queried 1,277 libraries and has received responses from 1,085 to date. (This is a fairly impressive response rate, but as Peterson points out, public institutions are legally required to respond to such requests within 10 days. Unfortunately his research project does not have the funds to pursue the 192 non-responders in court.) Of those, only 18 had anything on file to report, and only two of that number — both of them schools — had actually removed the challenged materials from their collections.

While it may be tempting to attribute the low rate of challenges and bans to “Massachusetts’ legendary and well-deserved reputation of commitment to education, access to information, and freedom of thought,” there is another likely factor that Peterson identified during the project:

[T]he Massachusetts records retention guidelines for public libraries only require libraries to retain ‘complaint and censorship records’ until the complain[t] is resolved. This is a bizarre hole, both generally as a matter of public policy and specifically for the purposes of this research. Any records we received were, by definition, above and beyond what the state requires public libraries to retain and make available. If there is one policy recommendation I have after this campaign, it is to have Secretary [of State] Galvin change this and require libraries to retain such records for a period of years for research purposes.

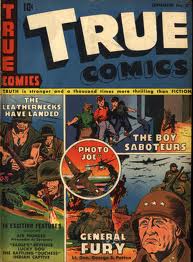

Nevertheless, many of the responding libraries did provide Peterson with records that reached much farther back than 2010. For instance, the Malden Public Library produced a 1948 letter from an unnamed librarian in response to a 6th grade teacher and nun who had asked that her students be prevented from checking out comic books. While the library deserves some credit for collecting any comics at all in 1948 and the librarian’s annoyance at the request was evident (“it seems odd that only one class in one school of the many schools of the city should not be allowed access to this type of reading”), the letter did not exactly strike a blow for freedom of speech. First, the librarian pointed out that the sole comic series in the library collection, True Comics, was published by Parents’ Magazine to entice “readers of the ordinary comics” (e.g. the ones not found in the library collection) and “lead them to ask for better types of books.” Even so, the librarian concluded that the staff would “attempt to co-operate with the teacher in refusing this magazine to the members of her class.”

Comics and graphic novels fared much better in more recent challenges, however. In response to a parent who was disappointed that her 18-year-old son found Troop 142 in Pepperell’s Lawrence Library, the Board of Trustees said that “the removal of this book from the collection would be censorship which we cannot support because this is a road with no end.” In another case, a Worcester parent copied the local library on a letter addressed to Marvel, criticizing the extreme gender imbalance in the early-reader series Super Hero Squad. The parent did not request any specific action from the library, and the collection still includes six titles from the series.

Kudos to Chris Peterson and MuckRock for shedding light on challenges and bans in Massachusetts–as well as on the shortcomings of the state’s public records laws. Here’s hoping it will inspire similar projects across the nation!

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.