Welcome to Using Graphic Novels in Education, an ongoing feature from CBLDF that is designed to allay confusion around the content of banned books and to help parents and teachers raise readers. In this column, we examine books that have been targeted by censors and provide teaching and discussion suggestions for the use of such books in classrooms.

“What is China but a people and their stories” – Gene Yang, Boxers p. 312

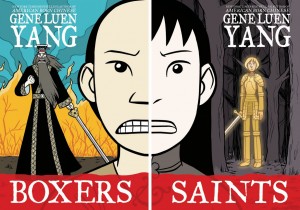

This month, we take a closer look at Boxers & Saints by Gene Luen Yang (First Second Books, 2013).

Boxers & Saints (First Second Books, 2013) was recently placed on the short list for the 2013 National Book Award for Young Peoples Literature — the second time a graphic novel has been nominated. (The first American Born Chinese, also by Gene Yang, was nominated in 2006.)

We highlight Boxers and Saints here for two reasons: first, in honor of its prestigious nomination; but even more importantly, because this two-book set illustrates the importance of understanding and analyzing conflict from multiple perspectives, in the hope of teaching and reaching greater understanding and tolerance.

Boxers and Saints’ double volumes revisit the Chinese Boxer Rebellion (1899-1900), sensitively and evenhandedly relating Chinese peasants’ perspectives from each side of the conflict. Boxers tells the story of the illiterate peasants tired of being hungry, tired of failing farms, and tired of Chinese Christian ruffians who would steal, cheat and beat them while under Western protection. It is young Bao who leads them as they turn into vengeful warrior gods, supporting fellow villagers and ridding China of the “white devil’s” influence. Saints tells the story of Four-Girl a peasant girl, who shunned by her family finds compassion and belonging with Christian converts. Both Four-Girl (who later assumes the Christian name Vibiana) and Bao believe it is their life’s mission to fight their foes and unite their divided and beloved China.

Table of Contents

- BACKGROUND

- OVERVIEW

- SUMMARY

- TEACHING/DISCUSSION SUGGESTIONS:

- COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS (CCSS)

- ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

BACKGROUND

Factors Leading to Rebellion

Towards the end of the 19th century, China was experiencing a series of political, environmental and economic challenges, severely weakening the Ch’ing (Qing) dynasty. In addition to natural disasters (floods, famine and droughts), China found itself shattered by a century of wars and could no longer defend its borders.

Western powers, with advanced weapons and modernized military, along with their profitable opium trade, were pushing China to accept foreign control over its economic affairs. Foreigners came and gained concessions from the Qing dynasty, and parcels of land were placed under their jurisdiction and functioned as colonies. In addition to Western governance and cultural influences, missionaries came to China to convert the masses and merchants came looking for gold and trade opportunities.

While the Qing dynasty welcomed Western trade, opium infected China’s citizens affecting the country’s national defense and agricultural production. The ensuing Opium Wars (with Britain, 1839-42, and the Anglo-French, 1865-60) arose from China’s attempts to suppress the opium trade. A few decades later, the Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) weakened China even further. Japan in the late 19th century fought China for control over Korea, which was a Chinese tribute state. Under the Tientsin Convention of 1885, both China and Japan had the right to send troops into Korea. In 1894 a rebellion broke out in Korea (the Tonghak Rebellion) and Japan used this as a pretext for war, successfully gaining control in the area.

Finally, economic disruption caused by opium addicted farmers who could no longer work, severe drought, famine, and flooding, coupled with the growing spheres of foreign influence and dominance, led the struggling, starving peasants (primarily from the Shandong Province) to revolt. Furthermore, as their economic situation worsened, foreign soldiers and gangs of roaming bandits victimized peasants and villagers, and many citizens were deeply embarrassed by their nation’s weakness. Traveling Chinese opera troupes would go from village to village attempting to relieve the pressure and relive Chinese glory. These operas (an extension of their pop-culture) inspired many of the young men to relive these stories and myths and return China to its former prosperity and grandeur.

1989-1900 The Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion was led by the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist, a secret society of peasants whose goals were to rid China of foreign influence (political, religious, social, and economic) and to unite China, restoring it’s honor, long-held customs, and prosperity.

The Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist believed that martial arts training, discipline, and prayer would empower them to perform extraordinary feats of fight and flight, and that spirit soldiers would descend from the heavens and assist them in purifying and uniting China. They also believed that their marital arts rituals protected them from foreign bullets, empowering them to defeat the white devils, their powerful military, and the ”secondary hairy ones” –- their Chinese Christian convert compatriots, many of whom they deemed lawless ruffians who received absolution of their crimes upon conversion.

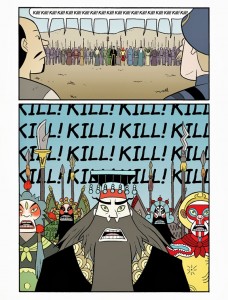

After several months of growing local violence and the increasing Christian presence in Shandong and the North China plain, Boxer fighters united and converged on Beijing (then called Peking) in June 1900 with the slogan “Support the Qing, exterminate the foreigners.” They destroyed churches and railroad stations and attacked the Dagu Forts along their way, massacring missionaries and Chinese Christians. The Empress Dowager Tzu’u Hzi initially supported the Boxers, and on June 21st authorized war on foreign powers. Foreign diplomats, civilians, soldiers, and Chinese Christians sought shelter and protection in the Legation Quarter, put under siege for 55 days. Chinese soldiers and Boxers set fire to areas north and west of the British Legation Quarter and the Hanlin Academy (a complex housing irreplaceable Chinese books and scholars) was destroyed. The Eight-Nation Alliance (Italy, France, Austria-Hungary, Japan, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) brought 20,000 troops — armed with advanced weapons and training — to China and defeated the Imperial Army and captured Beijing on August 14.

On September 7, 1901 the Boxer Protocol went into effect, calling for the execution of Chinese government officials who supported the Boxers and providing provisions for foreign troops stationed in Beijing and reparations of $330 million — more than the government’s annual tax revenue — to be paid to the eight nations over the next 39 years. The Qing dynasty, established in 1644, came to an end and China became a republic in 1912.

OVERVIEW

In Boxers, Yang deftly relates the Boxers’ perspective through the stories of Bao, an illiterate peasant boy who, like the Chinese gods of the opera and China past, fights for Chinese culture and honor. In Saints, Yang relates the Chinese Christians’ perspective through Four-Girl/Vibiana, who believes that she must become a “maiden warrior” like Joan of Arc, defending her home and country against the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist.

Both Vibiana and Bao have dreams and visions of gods, both want to help China, and both struggle with finding and maintaining their chosen paths. And, while their stories are separately told, they intersect, and complement each other. Bao’s story is somewhat longer and told in pastel colors, while dreams and meetings with Ch’in Shih-huang (the patron god he becomes when invoking the martial arts incantation) contain vivid colors and color patterns accenting the drama and feel of Chinese opera. Four-Girl/Vibiana’s story is told in monochromatic sepia tones, although Joan of Arc and her story are told in vibrant, rich gold and yellows.

Both stories relay China’s struggle to maintain its culture and honor under increasing Western influences and incursions. Both stories relay the struggles of faith, racism, and the feeling of isolation and humiliation felt by Chinese peasants. Both stories emphasize the protagonists’ goals of strengthening and uniting China through misguided myth. Both stories relate the coming of age of their characters and of their country.

Here is a YouTube trailer and a more detailed look at their story.

SUMMARY

When holding this enticing two-book set, I experienced a moment of panic — which one comes first? In truth (and hindsight) I don’t think it matters. Each tells the story of the Boxer Rebellion from their respective perspectives. Boxers is the story of oppressive events leading to the formation of The Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist and its quest to ‘free’ China. Saints relates why Chinese peasants converted (some for absolution of crimes others for a sense of belonging, community and belief) and tells of Christian persecution. Each book follows its respective path to Peking and the violent culmination of the Boxer Rebellion. That said, I might recommend reading Boxers first, as Saints seems to tie things up a bit tighter at the end.

Boxers tells Bao’s story. Bao, the third son in a family of three boys works on the family farm, often dreaming of spring, when the traveling opera troupes come to perform. In 1894 a Chinese Christian ruffian comes to the village, steals from them, and a fight ensues. Father Bey later comes to the village demanding “justice.” After Father Bey smashes the village’s earthen image of Tu Di Gong, the local earth god, the village constable finds himself helpless and while they would like to complain to the magistrate, the elders comment, “The Imperial government is like a toothless dog with these foreigners. The Chi’ing couldn’t even defend us Against Japan! Defeated by those midget barbarians! How humiliating!”

Shortly thereafter, a young man known as Red Lantern Chu comes to the village and trains the men in martial arts. They learn how to defend themselves and their village, and when they hear of neighboring village problems, they go to help them. Bao, whom his brothers feel is too young for the training, observes,and eventually receives personal training at night from Red Lantern. When the brothers go out with Red Lantern to help others, Red Lantern sends Bao on a different quest. It is on this quest that Bao finds Master Big Belly, who continues Bao’s training and eventual reveals a martial arts ritual/magic in which one bows, writes an incantation on parchment, burns the incantation and swallows it, closes his eyes, and exhales. When he does this, Bao finds himself transformed into one of the opera gods of early Chinese history.

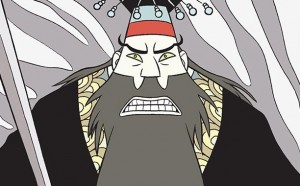

On his way back to the village, Bao finds that his brothers and their brother-disciples have been taken prisoner. He performs the martial arts ritual, becomes a god, and saves them. He trains them, and they become the Big Sword Society and later the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist. Each member becomes a different god. While Bao doesn’t know who he is at first, he discovers through a series of dream sequences that he transforms into Ch’in Shih-huang — “the First Divine Sovereign…[who] forged China from the blood and spirit of seven warring kingdoms! With my own fist, I brought her righteousness and harmony!”

The remainder of the book relates the Boxers’ campaign to reclaim the might and honor of China. We learn about their disciplined training and belief in their mythical powers. And we are with them as they march across China, killing European missionaries, merchants, soldiers, and Chinese Christians in their quest to vanquish Western influences, defend their culture, and struggle for greater economic stability.

In Saints, it is the Chinese Christians who are the protagonists, as relayed through the struggles of Four-Girl, the fourth girl and only child to survive in her family. Her grandfather refuses to name and accept her because she was born the fourth child on the fourth day of the fourth month, and “four, after all, is a homonym of death…” At one point her grandfather calls her a devil and she struggles to find and embrace who she really is. Her mother takes her to an acupuncturist because she has adopted a “devil face.” There, she sees a crucifix and notices the image of “a small sculpture of an acupuncture victim” around the doctor’s’ neck. She comes back later to ask about it, and as he tells her more about Jesus and Christian faith, the doctor’s wife gives Four-Girl cookies. As she walks through the woods ,she has visions of Joan of Arc and returns to the acupuncturist to learn more. Aside from the acupuncturist’s stories, lessons, and gospel, she learns that upon embracing the Christian faith she would be given a Christian name — she choses the name Vibiana. The cookies, the sense of belonging, finally having a name, and the influence of her encounters with Joan all push her to convert.

The rest of the story follows Vibiana, along with the doctor, his wife and Father Bey as they struggle with their own issues around opium, belonging, community, faith, human rights, and violence experienced from the hands of the Boxers.

In short, Boxers and Saints provides a stellar example of how we are the products of the world around us. The order of our birth, the names we are given (and try to live up to), the stories, songs, myths, and faiths we grow up with and hold as true, the political and economic situations we find ourselves in – all are integral in defining who and what we are. In creating a story in two volumes, Yang also shows us the importance of and challenge of trying to understand conflicting perspectives and cultural influences.

Throughout Boxers & Saints, Yang relays:

- The importance of perspective and of considering diverse points of view;

- The effects of racism and blind acceptance of “fact” and of “accepted truths”;

- The struggle of individuals’, of communities’, and of a country’s sense of identity and purpose;

- The development of local and of national heroes and understanding how these heroes came to be;

- The power of pop culture and environmental influences in shaping us;

- The powers and limits of local and national government in times of civic unrest and international imperialism;

- The powers and perils of rebellions;

- The power of “community” and cultural identity.

TEACHING/DISCUSSION SUGGESTIONS:

The Power of Cultural Heritage, Faith, and Perspective

- Research the source of the name “Vibiana” (Saint Vibiana) and discuss why Four-Girl may have chosen this name.

- Research, compare, and contrast the stories of Saint Vibiana and Joan of Arc. What are their similarities and differences? What might the choices these women made tell us about Four-Girl?

- Chart the positive things the Boxers and the Saints did for their respective communities. Then chart the negative things they did to others’ as they responded to feelings of humiliation and persecution. Discuss who the “winners” and “losers” are — if any exist at all.

- Discuss what it feels like to have your rights and beliefs threatened. What are the various options one might take to protect them?

- Discuss how Four-Girl/Vibiana and Bao each felt helpless with their given circumstances. Discuss how and when your students might feel helpless. Discuss strategies and means of alleviating these feelings.

- Compare and contrast how Bao and Four-Girl/Vibiana grow and change over the course of their stories. How are the choices they made similar, and how are they different?

- Discuss the power of pop culture in late 19th Century China, specifically the role Chinese opera and martial arts played for the Boxers. Discuss examples of how pop culture influences people today.

- Discuss the role of superstitions as seen in the Boxers & Saints (for example: Four-Girl’s being fourth how four is equated with death; the use of chants and incantations; the power of visions), versus how we express and deal with superstitions in our world today.

- Define and discuss racism and sexism

- Compare and contrast the different instances of discrimination, sexual discrimination, and racism presented throughout the two books.

- Discuss how hurtful racism can be — to those targeted as well as to the general population.

- Discuss the role racism played in the early 20th Century and the role it plays today (nationally and internationally) shaping policies and politics.

The Role of Governance

- Discuss the pros and cons of imperial colonialism and how it created, shaped and influenced our world today.

- Research (see links below) and discuss the events leading to the weakened Chinese government prior to the Boxer Rebellion and how China’s lose governing and colonization of the provinces fueled the growing resentment towards the West.

- Discuss local, national, and international ramifications of weak governance.

- Discuss the Five Edicts of the Big Sword Society (Honor your father and mother; Do not lust after women or wealth; Resist corruption wherever it’s found; Have compassion for the weak; Guard your fellow Brother-Disciples with your life). Compare them to the Bible’s ten commandments. If your students were forming a society for the betterment of others, what edicts or laws might they want dictating their actions and society.

- Discuss the power of these edicts and the power of commandments and laws. Why are they necessary?

Language, Literature, and Language Usage

- Discuss Gene Yang’s statement in Boxers, p. 312, “What is China but a people and their stories.”

- Plot and compare the author’s use of vocabulary, slang, idioms, color, and images as he relays the Boxers and the Saints’ respective stories. Is there a difference in their use of language? Why/why not?

- Boxers & Saints is rich in cultural stories. Have students collect their own respective family or community’s stories of beliefs, myths or faith.

- Search for and discuss Yang’s use of inference, simile, and metaphor

- Evaluate Yang’s use of language. You might:

- Search and discuss how the Chinese referred to Westerners and to each other (i.e. “pale-faced devils,” “black-headed people,” Master Big Belly, Father Bey is the “smasher of Gods,” a train is “the foreign devils fire cart” and others). Conversely, research/discuss how Westerners described the Chinese peasants in the early 19th century.

- Discuss Four-Girl’s reaction to a crucifix the first time she sees one (“an acupuncture victim”). Why did she view it this way?

- Discuss Yang’s use of language as Bao rationalizes why he could leave his father (Boxers, p. 60), noting the vow he made earlier to his father, “…was a vow made to another man, in another time.”

Modes of Storytelling and Visual Literacy

In graphic novels, images are used to relay messages with and without accompanying text, adding additional dimension to the story. Compare and contrast the author’s use of verbal versus visual imagery. Discuss with students how images can be used to relay complex messages. For example:

- In both volumes of Boxers & Saints, there are dream sequences. Discuss the role dreams play in relating the protagonists’ stories. Compare and contrast how the dream sequences are relayed in each book.

- Compare and contrast the colors used in Boxers versus the colors used in Saints. Why are they different, and what message is Yang trying to relay through his color choices?

- Discuss how the images complement the text, and ask students to add details and inferences of their own. For example, in Boxers, p. 84, the text reads: “Ever since Red Lantern left, food has been difficult to come by” and we see images of old and young villagers reaching for whatever bark is left on a lone tree in their village. How does this image support, complement, and reinforce the text?

- Compare and contrast the differences in how the Western god is portrayed versus how the Chinese gods are portrayed. Why is this important?

Suggested Prose Novel and Poetry Pairings

For greater discussion of literary style, related fictional histories and non-fiction texts you may want to read the following suggestions with Boxers & Saints:

- D’Aulaires Book of Greek Myths by Ingri and Edgar D’Aulaire: An introduction to the gods and goddesses of ancient Greece. Note that George O’Connor (First Second Books) is also putting out an exceptional collection of graphic novels that accurately and creatively retell the stories of the Greek gods. Use this book when discussing different gods of different cultures and times.

- The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck: About a farmer in a small village in China, post Boxer Rebellion, pre pre-revolutionary China. (Young Adult)

- East Wind, West Wind by Pearl S. Buck: About a family facing cultural change in early 20th Century China. (Young Adult)

- Imperial Woman by Pearl S. Buck: About Tzu His, China’s last empress, who ruled during the 19th Century. (Young Adult)

- Spring Moon by Bette Bao Lord: About five generations of a Chinese family during the period of war and cultural change that took place during the late 19 and early 20 Centuries. (Young Adult)

- Spring Pearl: The Last Flower by Laurence Yep, Kazuhiko Sano (illustrator): About 12 year-old Chou Spring Pearl, who is taken to live in the home of her father’s wealthy benefactor after the death of her parents. Chou must deal with her own battles as the Opium Wars rage around her. (Ages 9-12)

COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS (CCSS)

This book of assimilation and racial tolerance is full of advanced vocabulary, simile, slang, idioms, and cultural folklore. It promotes critical thinking, relates a hero and a coming of age story laden with issues of identity, justice and friendship, provides verbal and visual story telling that addresses multi-modal teaching, and meets Common Core State Standards including:

- Key ideas and details: Citing textual evidence to support analysis and inference, determining a theme or central idea, describing how a plot unfolds, analyzing how particular elements of the story interact; analyzing how particular lines of dialogue or incidents of a text reveal aspects of a character or provoke a decision; analyzing a particular point of view or cultural experience reflected in a work of literature from outside the United States, drawing on a wide reading of world literature.

- Craft and structure: Determining the meaning of words and phrases including figurative and connotative meaning; analyzing how particular sentences, chapters, scenes or stanzas fit into the overall structure of a text; explaining how a point of view is developed; analyzing how a text’s structure or form contributes to its meaning; analyzing a particular point of view or cultural experience reflected in a work of literature from outside the United States, drawing on a wide reading of world literature; determining the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to domains related to history/social studies; describing how a text presents information

- Integration of knowledge and ideas: Comparing and contrasting texts; distinguishing among fact, opinion, and reasoned judgment in a text; analyzing how a modern work of fiction draws on themes, patterns of events, or character types from myths, traditional stories, or religious works describing how the material is rendered new; analyzing how an author draws on and transforms source material in a specific way.

- Range of reading and level of text complexity: By the end of the year, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, in the grades 6-8, and in the grades 8-10 text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

- Knowledge of language: Using knowledge of language and its conventions when writing, speaking, reading, or listening; applying knowledge of language to understand how language functions in different contexts, to make effective choices for meaning or style and to comprehend more fully when reading or listening.

- Vocabulary acquisition and use: Determining the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases; demonstrating understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in world meanings; and acquiring and using accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases.

- Research to build and present knowledge: Drawing evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research;

- Comprehension and collaboration: Engaging effectively in a range of collaborative discussions building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly.

- Presentation of knowledge and ideas: Presenting claims and findings, sequencing ideas logically and using pertinent descriptions, facts, and details to accentuate main ideas or themes.

This book and related discussions also cover the following themes identified by The National Council for the Social Studies:

- Culture and Cultural Diversity – “…students need to comprehend multiple perspectives … to consider the strengths and advantages that this diversity offers to the society in general and to their own growth…to analyze the ways that a people’s cultural ideas and actions influence its members…”

- Time, Continuity, and Change – “…facilitate the understanding and appreciation of differences in historical perspectives and the recognition that interpretations are influenced by individual experiences, societal values, and cultural traditions… examine the relationship of the past to the present and extrapolating into the future… provide learners with opportunities to investigate, interpret, and analyze multiple historical and contemporary viewpoints within and across cultures related to important events, recurring dilemmas, and persistent issues, while employing empathy, skepticism, and critical judgment…”

- Individual Development and Identity – “…describe how family, religion, gender, ethnicity, nationality, socioeconomic status, and other group and cultural influences contribute to the development of a sense of self…have learners compare and evaluate the impact of stereotyping, conformity, acts of altruism, discrimination, and other behaviors on individuals and groups…”

- Individuals, Groups, and Institutions – “…help learners understand the concepts of role, status, and social class and use them in describing the connections and interactions of individuals, groups, and institutions in society…analyze groups and evaluate the influence of institutions, people, events, and cultures in both historical and contemporary settings…identify and analyze examples of tensions between expressions of individuality and efforts of groups and institutions to promote social conformity…”

- Power, Authority, and Governance – “…understanding the historical development of structures of power, authority, and governance and their evolving functions in contemporary American society… enable learners to examine the rights and responsibilities of the individual in relation to their families, their social groups, their community, and their nation… examine issues involving the rights, roles, and status of individuals in relation to the general welfare…explain conditions, actions, and motivations that contribute to conflict and cooperation within and among nations…challenge learners to apply concepts such as power, role, status, justice, democratic values, and influence…”

- Civic Ideals and Practices – “…assist learners in understanding the origins and continuing influence of key ideals of the democratic republican form of government, such as individual human dignity, liberty, justice, equality, and the rule of law…analyze and evaluate the influence of various forms of citizen action on public policy…evaluate the effectiveness of public opinion in influencing and shaping public policy development and decision-making…”

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

- http://www.history.com/topics/boxer-rebellion– provides a brief synopsis of events leading up to the rebellion, facts of the rebellion itself, and a view of its aftermath.

- http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/wars_boxer.html – a detailed background of the Boxer Rebellion

- http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/opium_wars_01/ow1_essay01.html – a verbal/visual history of the Opium Wars (by Peter C. Perdue) with outstanding maps, images and detailed text

- http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/heroin/etc/history.html – a fascinating time line of opium (use, trade, and influence) throughout history

- http://www.victorianweb.org/history/empire/opiumwars/opiumwars1.html – a detailed history of the Opium Wars with references for further reading

- http://sinojapanesewar.com/ – a verbal/visual history of the Sino-Japanese War

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Museum_of_the_War_of_Chinese_People%27s_Resistance_Against_Japanese_Aggression – details about The Museum of the War of Chinese People’s Resistance Against Japanese Aggression in Beijing.

- http://geneyang.com/boxers-and-pop-culture – Gene Yang discusses the Boxer Rebellion and the power of pop culture

- http://geneyang.com/how-chinese-opera-and-american-comics-are-alike – Gene Yang explains how Chinese opera and American comics are alike.

- http://geneyang.com/saints-boxers-saints – Gene Yang’s web page with additional information, interviews and resources

Meryl Jaffe, PhD teaches visual literacy and critical reading at Johns Hopkins University Center for Talented Youth OnLine Division and is the author of Raising a Reader! and Using Content-Area Graphic Texts for Learning. She used to encourage the “classics” to the exclusion comics, but with her kids’ intervention, Meryl has become an avid graphic novel fan. She now incorporates them in her work, believing that the educational process must reflect the imagination and intellectual flexibility it hopes to nurture. In this monthly feature, Meryl and CBLDF hope to empower educators and encourage an ongoing dialogue promoting kids’ right to read while utilizing the rich educational opportunities graphic novels have to offer. Please continue the dialogue with your own comments, teaching, reading, or discussion ideas at meryl.jaffe@cbldf.org and please visit Dr. Jaffe at http://www.departingthe text.blogspot.com.

All images (c) Gene Luen Yang