In 1972, a movie theater manager in Albany, Georgia, was convicted under a Georgia statute for the crime of distributing obscene material for showing the film Carnal Knowledge. The conviction took place during an odd limbo period between the decisions of Memoirs v. Massachusetts and Miller v. California. In Jenkins v. Georgia, the Supreme Court held in light of the new Miller standard for obscenity that lower courts had gone too far in classifying the movie as obscene, and the conviction was reversed.

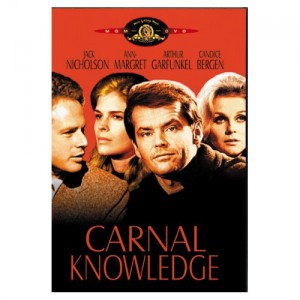

Mr. Jenkins was managing a movie theater, who, like many other movie theaters at the time, was showing the film Carnal Knowledge, a 1971 comedy-drama film directed by Mike Nichols that starred Jack Nicholson, Art Garfunkel, Candice Bergen, and Ann Margret. The movie focuses on two college roommates and lifelong friends, played by Nicholson and Garfunkel. It follows their friendship from their college years until middle age. The film focuses Nicholson and Garfunkel’s relationships with various women throughout the years. The film received many positive reviews and appeared on many “Ten Best” lists for 1971. It also received nominations for two Golden Globes and one Academy Award.

On January 13, 1972, Albany police obtained a search warrant for Jenkin’s theater, and they seized the film. Jenkins was then charged and convicted under a Georgia statute for the distribution of obscene material. He was fined $750 and sentenced to 12 months probation. Jenkins appealed to the Supreme Court of Georgia, who upheld the lower court’s conviction. He then appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, which eventually reversed the decision.

Under the holding of another case, Hamling v. United States, it was ruled that defendants who were convicted prior to the announcement of the Miller case but were still on direct appeal should receive the benefits from the new Miller test. Luckily for Jenkins, his case was exactly the type to which that holding was directed.

While the Miller test mostly involved questions of facts, which are to be determined by the jury, the Court did not want to give the jury unrestrained authority to determine if the film was “patently offensive” or “appealed to prurient interests.” They realized that those terms were greatly undefined and very confusing, so their review would need to contain some guidelines. They noted that Miller made it a point to not convict people “for the sale or exposure of obscene material unless these materials depict or describe patently offensive ‘hard core’ sexual conduct…”

Could a 1971 Academy Award nominee really contained “hard core” sexual conduct!? Miller took the time to give some examples of “patent offensiveness” which included “representations or descriptions of ultimate sexual acts, normal or perverted, actual or simulated,” and “representations or descriptions of masturbation, excretory functions, and lewd exhibition of the genitals.” It doesn’t really seem that the film Carnal Knowledge was something that could possibly be considered obscene under this test.

Justice Rehnquist writes about the Court’s viewing of the film:

Our own viewing of the film satisfies us that “Carnal Knowledge” could not be found under the Miller standards to depict sexual conduct in a patently offensive way. Nothing in the movie falls within either of the two examples given in Miller of material which may constitutionally be found to meet the “patently offensive” element of those standards, nor is there anything sufficiently similar to such material to justify similar treatment. While the subject matter of the picture is, in a broader sense, sex, and there are scenes in which sexual conduct including “ultimate sexual acts” is to be understood to be taking place, the camera does not focus on the bodies of the actors at such times. There is no exhibition whatever of the actors’ genitals, lewd or otherwise, during these scenes. There are occasional scenes of nudity, but nudity alone is not enough to make material legally obscene under the Miller standards.”

In other words, the Court recognized that the film was not at all what the Miller test considered to be obscene. It was not “hard core sexual conduct for it’s own sake.” The film could not be held to show sexual conduct in a patently offensive way and therefore does not fall outside of the protection of the First Amendment.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by making a donation or becoming a memberof CBLDF!

Eric Margolis is a 3L at St. John’s Law School who wishes to pursue a career in Entertainment / Intellectual Property law. You can contact him at EricMargolis310@gmail.com!