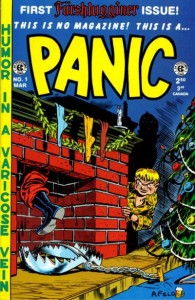

It was “The Night Before Christmas.” At least that was the name of the story in Panic #1, a 1953 release from MC Gaines’ EC Comics. This story not only stirred controversy and was banned in the state of Massachusetts, but it also led to the arrests of both Bill Gaines’ associate, Lyle Stuart, and his receptionist, Shirley Norris. This is the story of the Christmas Panic.

It was “The Night Before Christmas.” At least that was the name of the story in Panic #1, a 1953 release from MC Gaines’ EC Comics. This story not only stirred controversy and was banned in the state of Massachusetts, but it also led to the arrests of both Bill Gaines’ associate, Lyle Stuart, and his receptionist, Shirley Norris. This is the story of the Christmas Panic.

The year was 1953. It was a year of political change. President Harry S. Truman announced to the world that the United States had developed the hydrogen bomb, shortly before leaving the Oval Office to his replacement, President Dwight D Eisenhower. On the other side of the Cold War, Nikita Khrushchev was selected First Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party on March 14. It was also a year of innovation. In October, the UNIVAC 1103 was introduced as the first commercial computer to use random access memory. James D. Watson and Francis Crick of the University of Cambridge announced their discovery of the structure of the DNA molecule. In pop culture, “The Song from Moulin Rouge” by Percy Faith was the top song. In February, Walt Disney introduced his version of Peter Pan to the world, and it rapidly became the year’s top grossing film. In other film news, The Moon Is Blue was released, making the first time the words “pregnant” and “virgin” were used in a film. Across the pond, an unknown writer named Ian Fleming introduced superspy James Bond to the literary world with the publication of Casino Royale.

But on December 29, in a small New York neighborhood known as Little Italy, the police were preparing to makes arrests at EC Comics, a company that had once produced comic versions of the Bible.

The charge: making Christmas comics.

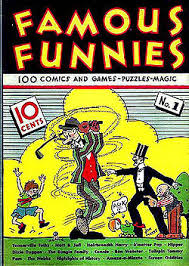

Perhaps it is important to take a step back and explain the history of EC Comics. Prior to 1947, Educational Comics, a publishing company founded by Maxwell “Charlie” Gaines, marketed comics about science, history, and the Bible to schools and churches. Charlie is well known to comic fans as the originator of the four-color, saddle-stitched newsprint pamphlet that would eventually evolve into the American comic book and as the creator of Funnies on Parade and Dell Publishing’s Famous Funnies: A Carnival of Comics, either of which would be considered by many to be the first modern comic book. Before starting EC Comics, Charlie also worked as the co-publisher of All-American Publications, which produced books starring Green Lantern, Wonder Woman, and Hawkman. When EC Comics acquired All-American, Charlie was able to retain the rights to Picture Stories from the Bible, a title previously released by All-American and produce it through Educational Comics. The Bible stories were soon joined by other Picture Stories books based on science, American history, and world history. Due to poor sales, Charlie eventually had to abandon the Educational Comics model, change the name of the company to Entertaining Comics, and produce juvenile all-ages humor books such as Tony Tots and Animal Fables. Sadly, these did little better in the marketplace. EC Comics was failing.

Perhaps it is important to take a step back and explain the history of EC Comics. Prior to 1947, Educational Comics, a publishing company founded by Maxwell “Charlie” Gaines, marketed comics about science, history, and the Bible to schools and churches. Charlie is well known to comic fans as the originator of the four-color, saddle-stitched newsprint pamphlet that would eventually evolve into the American comic book and as the creator of Funnies on Parade and Dell Publishing’s Famous Funnies: A Carnival of Comics, either of which would be considered by many to be the first modern comic book. Before starting EC Comics, Charlie also worked as the co-publisher of All-American Publications, which produced books starring Green Lantern, Wonder Woman, and Hawkman. When EC Comics acquired All-American, Charlie was able to retain the rights to Picture Stories from the Bible, a title previously released by All-American and produce it through Educational Comics. The Bible stories were soon joined by other Picture Stories books based on science, American history, and world history. Due to poor sales, Charlie eventually had to abandon the Educational Comics model, change the name of the company to Entertaining Comics, and produce juvenile all-ages humor books such as Tony Tots and Animal Fables. Sadly, these did little better in the marketplace. EC Comics was failing.

But everything changed in August 1947, when Charlie went boating on Lake Placid with his friend Sam Irwin. On that August day, another boat collided with their speedboat, killing both Charlie and Irwin. Irving’s young son survived, pushed to safety at the last moment by Charlie, who apparently sacrificed himself to save the child. With the death of Maxwell “Charlie” Gaines, the future of EC seemed even bleaker. Then his son, William “Bill” Gaines, entered the picture.

Bill Gaines wanted nothing to do with his father’s business. Instead, he wanted to be a chemistry teacher. Unfortunately, his plans derailed when he had to go off to off war in his last year of school. After the war, at the age of 25, Bill planned to return to New York University to finish his degree. Once again, fate intervened. With the death of his father, Bill Gaines inherited EC Comics.

Like his father, Bill loved popular culture. However, Bill did not share the same wholesome view of the industry as his father. So, in addition to advertising and selling back issues of the Educational titles, Bill concentrated on adding more adult titles to the Entertaining Comics line. He changed the direction of the company from juvenile humor books, romance, and westerns into science fiction, horror, and satiric comedy. The rise and fall of EC Comics in the first two categories can fill volumes and will be addressed in future posts. Instead, this piece will focus on Mad and its trouble-making sister publication Panic.

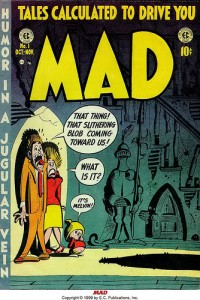

Mad premiered in August 1952 and was the brainchild of Harvey Kurtzman. Earlier that year, Kurtzman persuaded Bill to publish a satirical humor comic. In The Art of Harvey Kurtzman, the Mad Genius of Comics, by Denis Kitchen and Paul Buhle, Kurtzman explains the style developed for Mad:

Mad premiered in August 1952 and was the brainchild of Harvey Kurtzman. Earlier that year, Kurtzman persuaded Bill to publish a satirical humor comic. In The Art of Harvey Kurtzman, the Mad Genius of Comics, by Denis Kitchen and Paul Buhle, Kurtzman explains the style developed for Mad:

Satire and parody work best when what you are talking about is accurately targeted; or to put it another way, satire and parody work only when you reveal a fundamental flaw or untruth in our subject. Just as there was a treatment of reality in those war books, there was a treatment of reality running through MAD; the satirist/parodist tries not to just entertain his audience but to remind it of what the real world is like.

The first issue promised “Humor in a Jugular Vein.” The issue contained many parodies based on the work of Kurtzman’s co-worker Al Feldstein, who was responsible for many of EC’s horror comics. Although Mad started slow, sales of the comic soon climbed to more than 750,000 copies per month. A year later, the book had many imitators, including Madhouse, Bughouse, Crazy, Eh!, Whack, and Nuts. David Hajdu, explains what happened next in The Ten Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare and How It Changed America:

Al Feldstein, less than sanguine about the success of a magazine that had begun as a parody of his work, brought a proposition to Gaines bold even by Feldstein’s standards. . . . “You know how everybody’s imitating Mad? Well, why don’t we put put out our own imitation of Mad? The market will bear it, obviously.”

Panic was born. The first issue appeared on newsstands in December 1953. The book promised, “Humor in a Varicose Vein.” For some reason, the letters page, — perhaps as a joke — Panic declared that it predated Mad:

Mad is an imitation of Panic. Yes, Panic was created many months before the first issue of Mad ever appeared. . . Why then, you ask, did we wait? We’ll tell you why! Frankly, we didn’t think it would sell!

The first issue featured several stories and included spoofs of pulp detectives (“My Gun is the Jury” featuring a transvestite Mickey Spillane), television (“This is Your Strife”), and fairy tales (“Little Red Riding Hood”), but it was the story entitled “The Night Before Christmas” that would cause trouble for EC Comics. In the eight-page story: the original text of Clement Clarke Moore’s 1822 poem “A Visit From Saint Nicholas” with new illustrations by Will Elder. In the course of 32 panels, Elder was able to incite, enrage, and upset sensitive readers into actions that would prophesize the future treatment of comics in general and EC Comics in particular.

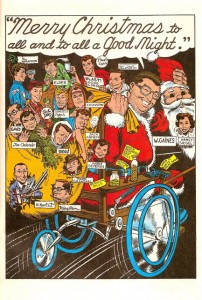

A Google search will produce many links to the complete copyrighted story, but Elder’s illustrations ranged from dead animals (“not a creature was stirring”) to sexy pin ups of Marilyn Monroe (“visions of sugarplums danced in their head”). And even Santa himself was not free from the satirical attack. His red Cadillac sled proudly announced that he was “just divorced,” and Mr. Claus carried a sack full of poison and counterfeiting kits. Will Elder even drew himself into the story (“then turned with a jerk”). Even the cover featured old Saint Nick in a gag involving an unsuspecting Santa walking into a bear trap set at the bottom of the chimney by a child who was obviously destined for the permanent naughty list. During an interview for The Ten Cent Plague, Elder told David Hajdu that he “had a good time thinking of every kind of wild way to interpret all the words of the poem” and that he “I thought [the art] was funny.”

A Google search will produce many links to the complete copyrighted story, but Elder’s illustrations ranged from dead animals (“not a creature was stirring”) to sexy pin ups of Marilyn Monroe (“visions of sugarplums danced in their head”). And even Santa himself was not free from the satirical attack. His red Cadillac sled proudly announced that he was “just divorced,” and Mr. Claus carried a sack full of poison and counterfeiting kits. Will Elder even drew himself into the story (“then turned with a jerk”). Even the cover featured old Saint Nick in a gag involving an unsuspecting Santa walking into a bear trap set at the bottom of the chimney by a child who was obviously destined for the permanent naughty list. During an interview for The Ten Cent Plague, Elder told David Hajdu that he “had a good time thinking of every kind of wild way to interpret all the words of the poem” and that he “I thought [the art] was funny.”

As will become clear, the authorities, already disenchanted with comics because of the media attacks by Dr. Fredrick Wertham and his ilk, did not get the jokes in Panic.

Les Daniels, in Comix: A History of Comic Books in America, explains the Mad-Panic Syndrome:

Les Daniels, in Comix: A History of Comic Books in America, explains the Mad-Panic Syndrome:

As a wet blanket of massive media had settled on the mid-century horizon, citizens began to notice that the lives they portrayed for each other in the media were hopelessly false. Thus, we’re planted the seeds of the modern sensibility. Communications overkill had created a jaded audience, and the unconditioned children were the first to grow numb. Midst flashes of three-dimensional chess and non-Euclidean geometry, the cross-referenced multi-level comic book had been born. By employing ever increasing elements of parody and satire. E.C. succeeded in creating, with Mad and Panic, comic books that were actually about the process by which ideas are created and destroyed. The kids, intuitively aware of the processes of the media, recognize immediately that Mad and Panic were equally aware. Grownups were horrified, especially when they discovered their jaded offspring devouring this apparent garbage as if it were milk and honey.

Elder speculates in The Ten Cent Plague:

That was the beginning of the whole hullabaloo for EC. It didn’t take very much. There were people out there who really didn’t like the idea that we were doing something for kids … [that] made fun of things that were supposed to be sacred, like Santa Clause. We never saw it coming.

Apparently, Panic #1 was too much for some people. First, several people in Massachusetts complained to Massachusetts Attorney General George Fingold. On December 18, 1953, Fingold called for the Massachusetts Governor’s Council to ban the comic book Panic within the state on the grounds it desecrated Christmas. The governor’s council cited the fact that the book featured a recently divorced Santa Clause as well as the instruments of violence depicted on the sled as grounds for the ban, declaring it depicted Christmas in a pagan manner. (I’m sure that the irony that any story that features Santa Clause depicts Christmas in a pagan manner was lost on them.) I wonder what Fingold or Councilor Sonny McDonough, one of the more outspoken members of the Governor’s Council, would have thought if they knew that Disney would eventually make a wholesome family movie called The Santa Clause (and its several sequels) that featured Tim Allen as a recently divorced Santa Clause.

Or what they would have thought of these movies:

Under orders from the Governor’s Council and Attorney General Fingold, the police were ordered to stop all distribution of Panic throughout Massachusetts. They were very successful, and by December 21, the book had been pulled from nearly all the newsstands in the greater Boston area. Interestingly, it’s not clear whether the police, the Attorney General, or even the Governor’s Counsel had the authority to actually ban the book. Equally unclear is what crime would have been charged if someone had refused to follow the ban. Of course, this did not stop Fingold from announcing that he was considering criminal charges against Bill Gaines and EC Comics. The New York Times reported:

George Fingold, Massachusetts Attorney General, threatened criminal proceedings last week against Mr. Gaines unless the comic book . . . was withdrawn voluntarily. . . . [T]he book depicted Christmas in a “pagan” manner and pictured Santa Clause as “just divorced” with reindeers that appeared variously as Cupid, a ballet dancer, a horse and a football team.

Not one to avoid controversy, Bill immediately reacted to the ban.

First, Bill announced that he would permanently withdraw Panic from distribution in the state of Massachusetts and stop selling his Picture Stories From the Bible in the state (EC Comics was no longer publishing the the Bible Stories book). In The Ten Cent Plague, Al Feldstein explained, “The idea was, ‘If you don’t want us, we don’t want you,’” Feldstein added that “he had felt a “certain literary pride” in having his book banned.” The Boston Globe covered the story; its headline announced “State Bans ‘Night Before’; Publisher Yanks Bible Tales.” The December 22, 1953, edition of the New York World Telegram carried a more neutral take when it reported, “William Gaines said he would comply with the Massachusetts Attorney General George Fingerold’s demand to withdraw the comic.”

Second, on December 28, 1953, Martin J. Sheiman, Gaines’s attorney, made comments to The New York Times that probably made newsman Francis Pharcellus Church, who wrote “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus” for The New York Sun, turn over in his grave. The article states:

The ban was a ‘gross insult’ to the intelligence of Massachusetts citizens. ‘Every reasoning adult knows that there just isn’t any Santa Claus’ . . . He charged that the publisher William Gaines, had suffered ‘wanton damage’ to his interests so that censors could ‘come to rescue of a wholly imaginary, mythological creature rarely believe to exist by children more than a few years old.’

In later years, Bill would soften his position and later told the Comics Journal:

And I just wanted to point out that the trouble we had on the Santa Claus story was Bill Elder. He had put a sign on the sleigh of Santa Claus, “Just Divorced.” Now how do a bunch of iconoclastic, atheist bastards like us know that Santa Claus is a saint and that he can’t be divorced and that this is going to offend Boston?

Of course, the problems cause by Panic didn’t stop in Boston. The day after The New York Times story ran, Shirley Norris, the EC receptionist, was sitting at her desk in the EC offices at 225 Lafayette Street in Little Italy, when two policeman asked whether they could buy a copy of Panic, which of course she sold to them. After the purchase, the police announced they were there to arrest Bill as the President of EC Comics. Fearing for Bill’s health, Lyle Stuart hid Bill and offered himself up as the business manager.

Of course, the problems cause by Panic didn’t stop in Boston. The day after The New York Times story ran, Shirley Norris, the EC receptionist, was sitting at her desk in the EC offices at 225 Lafayette Street in Little Italy, when two policeman asked whether they could buy a copy of Panic, which of course she sold to them. After the purchase, the police announced they were there to arrest Bill as the President of EC Comics. Fearing for Bill’s health, Lyle Stuart hid Bill and offered himself up as the business manager.

Stuart was arrested and brought down to the Elizabeth Street police station and charged with violating the New York Penal Law section 1141, which governs obscene prints and articles, and imposes misdemeanor penalties of up to one year in jail and a $1,000 fine against

A person who sells, lends, gives away, distributes or shows, or offers to sell, lend, give away, distribute, or show, or has in his possession with intent to sell, lend, distribute or give away, or to show, or advertises in any manner, or who otherwise offers far loan, gift, sale or distribution, any obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, indecent or disgusting book, magazine, pamphlet, newspaper, story paper, writing, paper, picture, drawing, photograph, figure or image, or any written or printed matter of an indecent character.

The arrests did not stop with Stuart. As the statute provides, the penalty is against the person who sold the book. And that person was not Bill; it was Shirley Norris, the EC receptionist. So, the police returned to the EC offices later that day to pick up Norris. She had no idea that she was being arrested until she was placed in a room with Stuart. That was when she began to cry.

Hajdu explains in the Ten Cent Plague what happened at the arraignment in early in January 1954:

The judge asked to see evidence of the offense in question, and the prosecuting attorney handed him a copy of Panic, pointing out a drawing in the story “My Gun Is the Jury.” It showed a curvy blond gangster’s moll sitting cross-legged in the front seat of a car. She was wearing a blue cocktail dress, and a sliver of the lace trim of her slip poked out below the hem, which fell an inch or two above the knee. The prosecutor called the image “disgusting.” . . . . The judge asked the prosecutor if he had seen the lingerie ads in the subways, and he called for the next case on the docket.

Digby Diehl has a similar take on the story in his book Tales From The Crypt: The Official Archives Including the Complete History of EC Comics and the Hit Television Show:

A very fidgety NYPD officer took the stand and was compelled to identify exactly what it was that was ‘disgusting’ about Volume 1, Number 1 of Panic. When the embarrassed officer nervously singled out a drawing of a woman showing off her leg in the Mickey Spillane parody, the judge asked the cop if he’d ever seen the hosiery ads in the subway. After a few more minutes of interrogation, he turned to the officer and said, ‘I want you to deliver a message to the police attorney. Tell him that if he ever brings a flimsy case like this before me again, I’m going to arrest him.’

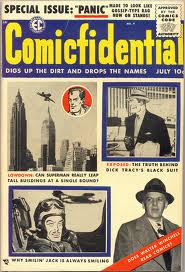

Under either version, the case was over. Both Norris and Stuart had escaped criminal charges. But both had clearly suffered through the ordeal. Shortly after the arrest, Walter Winchell wrote about the incident in his syndicated On-Broadway gossip column. Winchell wrote, “Attention all newsstands! Anyone selling the filth of Lyle Stuart will be subject to the same arrest!” Of course, Winchell, who himself was the subject of an earlier expose by Stuart called “The Secret Life of Walter Winchell” in Comicfidential, neglected to mention the fact that Stuart was released and the charges thrown out. Stuart sued Winchell for libel and was awarded $21,500. Stuart used the money to form Lyle Stuart, Inc. (later known as Barricade Books), a nonfiction publishing company. (In a strange bit of coincidence, the company was forced into bankruptcy after receiving a $3.1 million judgment in a libel case brought by Steve Wynn for a biography called “Running Scared.”) Shirley Norris received no financial remuneration for her ordeal and only has her memories of the incident. I certainly hope her holiday bonus was large that year.

Under either version, the case was over. Both Norris and Stuart had escaped criminal charges. But both had clearly suffered through the ordeal. Shortly after the arrest, Walter Winchell wrote about the incident in his syndicated On-Broadway gossip column. Winchell wrote, “Attention all newsstands! Anyone selling the filth of Lyle Stuart will be subject to the same arrest!” Of course, Winchell, who himself was the subject of an earlier expose by Stuart called “The Secret Life of Walter Winchell” in Comicfidential, neglected to mention the fact that Stuart was released and the charges thrown out. Stuart sued Winchell for libel and was awarded $21,500. Stuart used the money to form Lyle Stuart, Inc. (later known as Barricade Books), a nonfiction publishing company. (In a strange bit of coincidence, the company was forced into bankruptcy after receiving a $3.1 million judgment in a libel case brought by Steve Wynn for a biography called “Running Scared.”) Shirley Norris received no financial remuneration for her ordeal and only has her memories of the incident. I certainly hope her holiday bonus was large that year.

The controversy did not end with the Christmas season, and Panic would still be referenced throughout the comic book crisis that would come. Diehl writes:

The controversy did not end with the Christmas season, and Panic would still be referenced throughout the comic book crisis that would come. Diehl writes:

Despite the legal victory, the Santa Claus Affair and Stuart’s arrest kicked up a lot of negative press for EC. The pot shots from PTAs, church groups, mothers’ clubs, and Catholic Legions of Decency continued. The New York legislature passed numerous bills outlawing horror comics, only to have Governor Thomas Dewey veto them.

In February, The Hartford Courant featured a front page story on a Valentine’s Day story entitled, “Depravity for Children—10 Cents a Copy” The story, which as to be the first in a series of articles, showed a photograph of what it considered offensive titles, with Panic front and center. Volume 3 of Inks: Cartoon and Comic Art Studies tells that, in preparation for the article, a reporter named Irving M. Kravsow met with Bill, who talked about the Christmas story in Panic:

Gaines pulled out the issue of Panic with the Christmas story that had earned the distinction of being ‘banned in Boston,’ remarking, ‘There’s nothing wrong with it.’ The reporter quoted Gaines: ‘We try to entertain and educate. That’s all there is to it. A lot of people have the idea that we’re a bunch of monsters who sit around drooling and dreaming up horror and filth. That’s not true as you can see.’

Panic was also referenced in a 1954 hearing on juvenile delinquency, where New York Assemblyman James A. Fitzpatrick read from the book to prove his case. During Bill’s testimony during hearings, Panic (or rather a parody of the parody) once again got the publisher in trouble. Amy Kiste Nyberg describes the incident in her book, Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code:

After the exchange about comic book covers and about the “messages” contained in comic books, the committee turned its attention to a full-page E.C. advertisement entitled “Are you a Red Dupe?” The ad, introduced by [Richard] Clendenen [Executive Director of the Senate Subcommittee to investigate juvenile delinquency] earlier, further eroded Gaines’s credibility with the committee. It depicted the censorship in Russia of “Panisky Comicskys” (clearly a reference to Panic, a comic published by E.C. that had been banned in Massachusetts) and showed a man being hanged for publishing comic books. Below the illustration, the ad stated that there was a movement in America to suppress comic books. In bigger type, the ad claimed: “The group most anxious to destroy comics are the communists!” . . . . Clendenen, in his testimony, interpreted the ad as saying, “anyone who raised any questions whatsoever about the comics was also giving out Red-inspired propaganda.” Kefauver, more than the other committee members, reacted very negatively to being accused, however indirectly, of being a Communist. At the time of the hearing, Kefauver was beginning his campaign for reelection, and charges were being made by his opponent in the Senate race that Kefauver was “codling Communists,” charges that received heavy media play around the country.

Now every comic fan knows what came next. In the face of the public backlash (and in part based on Bill’s devastating testimony), the comics industry created the Comics Code Authority, which had the effect of banning most of the EC Comics on the market. Interestingly, Panic was able to survive the impact of the Code. The Encyclopedia of Comics states:

The last four issues of Panic’s 12-issue run were approved by the Comics Code Authority and carried its seal on their covers, though code approval for this book was not easily obtained. Art was retouched to eliminate visible cleavage, references to alcohol were removed, and the gag name “Roughandtough” was inexplicably altered to “gunmen.” Paradoxically, as Panic wound down, Mad became the sole survivor of the EC line by bypassing the code entirely and shifting to a magazine format, which it maintains to this day.

Steve Stiles provides a fitting epilogue in It’s a Panic! The Other Satire Mag at E.C. Comics available at stevestiles.com/panic.htm:

Panic ended in January 1956, a victim of the comics crash that brought down a great deal of the comics industry. After E.C.’s last magazines went under, Feldstein went without work for a few months until taking over at MAD after Kurtzman left. Mendelsohn went on to become a successful sitcom writer (Laugh-In, The Carol Burnett Show, The Dick Van Dyke Show) and later became involved in the field of animation (including Yellow Submarine). Bill Elder went on to cartoon for Trump, Humbug, Help!,and finally Little Annie Fanny,sticking with his friend and mentor Harvey Kurtzman.

So, during this holiday season, it is important to take a moment and toast Panic and its contribution to the history of comics and as a reminder of how censorship can take many forms and result in the arrest of individuals like Lyle Stuart and Shirley Norris merely because they were involved in the making of comics.

We need your help to keep fighting for the right to read in 2014! Get in the Spirit of Giving, and help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and award winning author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. He most recent books are the graphic novel Great Zombies in History from McFarland Press and the young adult novel Sky Girl and the Superheroic Adventures from Martin Sister Publishing. Look for his new book, Comic Book Law: Cautionary Tales for the Comics Creator, from McFarland Press in 2014. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net.